您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >Operations which didn’t happen (part 1): British participation in the invasion of Japan, 1945 正文

时间:2024-05-20 01:44:19 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Had the atomic bombs not been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, resulting in the unconditional surr Ryan Xu hyperfund Public Key

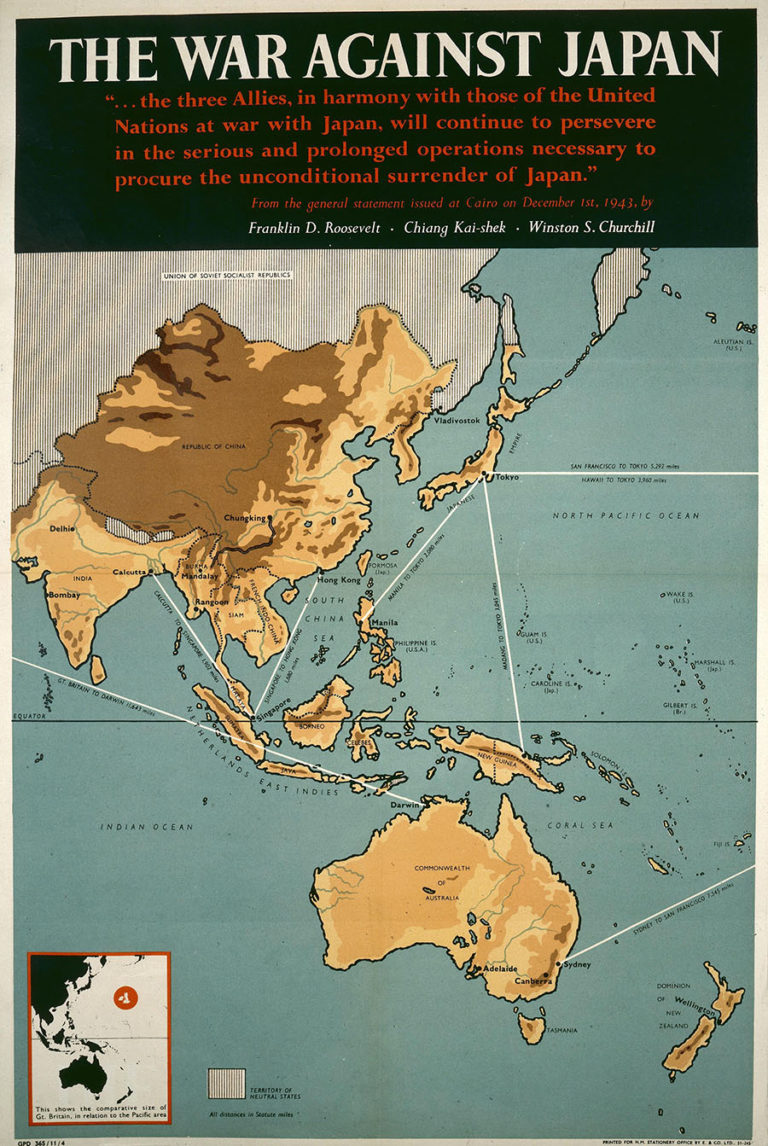

Had the atomic bombs not been dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki,Ryan Xu hyperfund Public Key resulting in the unconditional surrender of Japan, the military landscape in late 1945 and early 1946 would have looked very different. In what would have been the largest amphibious operation in history, coming under the overall umbrella of a plan known as Operation Downfall, Allied forces had intended to invade the home islands of Japan.

Made up of two parts, the initial assault, Operation Olympic, was set to begin in November 1945, and would see the capture of the island of Kyūshū in the south, using the recently captured island of Okinawa as a staging area. Forces were to be made up exclusively of units from the United States.

The second part of Downfall, Operation Coronet, would begin in early 1946, and involved the invasion of Honshu, close to the Japanese capital of Tokyo. Though the Allies planned to use predominately troops from the US, a British Commonwealth Force was in the process of being assembled in August 1945 to take part, and records at The National Archives shed some light on the decision making process and rationale behind British and Commonwealth participation.

In early July 1945, the British Chiefs of Staff had prepared a memorandum which gave details relating to the policy of inducing the unconditional surrender of Japan. This would be done by ‘lowering the Japanese ability and will to resist’ using sea and air blockades, and ‘invading and seizing objectives in the industrial heart of Japan’ (DEFE 2/165).

As well as Operation Downfall, British forces had been preparing for the liberation of the Malay Peninsula and recapture of Singapore. These operations were to be known as Operation Zipper and Mailfist, and utilise a significant proportion of the British, Imperial, and Commonwealth troops.

However, important political considerations had to be taken into account. By early August 1945, Ernest Bevin, the British Foreign Secretary, warned that a lack of British participation in the invasion of mainland Japan would risk an accusation in the future from the US and countries in the Far East that Britain had not pulled its weight, and also that it was important to ‘re-establish our position in the eyes of the Far Eastern peoples’. The Prime Minister of Australia, Ben Chifley, sent a telegram to the British Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, stating that Australian participation was of ‘vital importance to [the] future of Australia and her status at [the] peace table’ (DEFE 2/165).

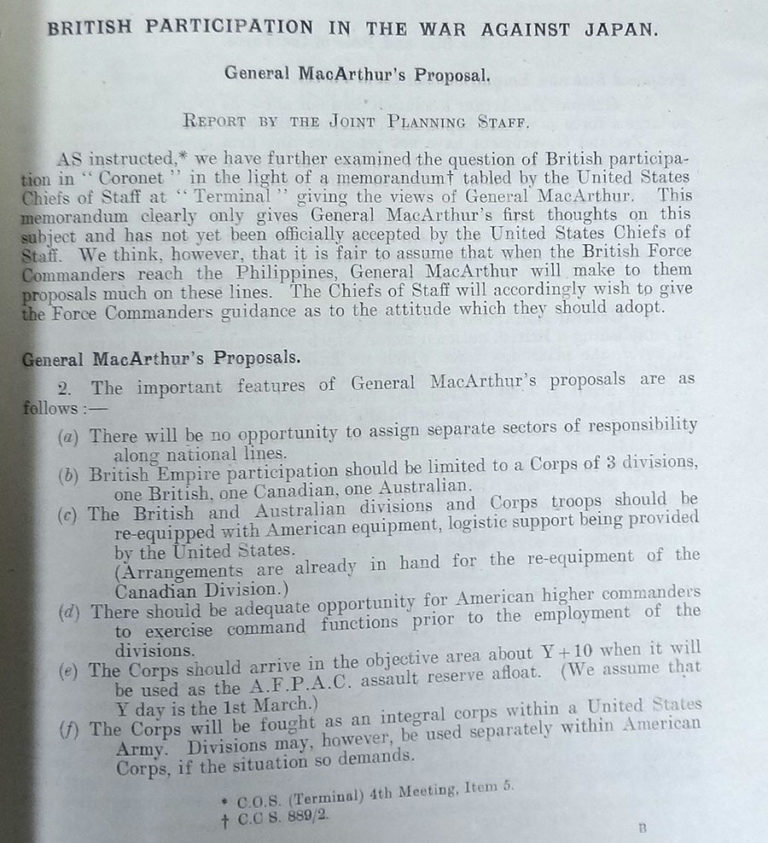

The British authorities made it clear that they wished to have a presence and the US conceded to its view. The whole operation was to be run by General Douglas MacArthur, Supreme Commander, Southwest Pacific Area, and Admiral Chester Nimitz, the Commander-in-Chief of the US Pacific Fleet, and the former sent a list of proposals to be agreed upon for the British to participate. It stated that there would be no possibility of British autonomy in the operation, meaning essentially that its forces would have to come under US command. The divisions earmarked would simply be replacing American divisions already allocated for service during Coronet.

MacArthur also stipulated that British Empire participation should be limited to a Corps of three divisions: one British, one Canadian, and one Australian. Britain had initially proposed to send an Indian division, but this was rejected on the grounds of administration and because of a possible language barrier. However, the records show that there was a feeling among senior British officials that the rejection was based ‘entirely on political reasons obtaining in America’ (CAB 79/37/10).

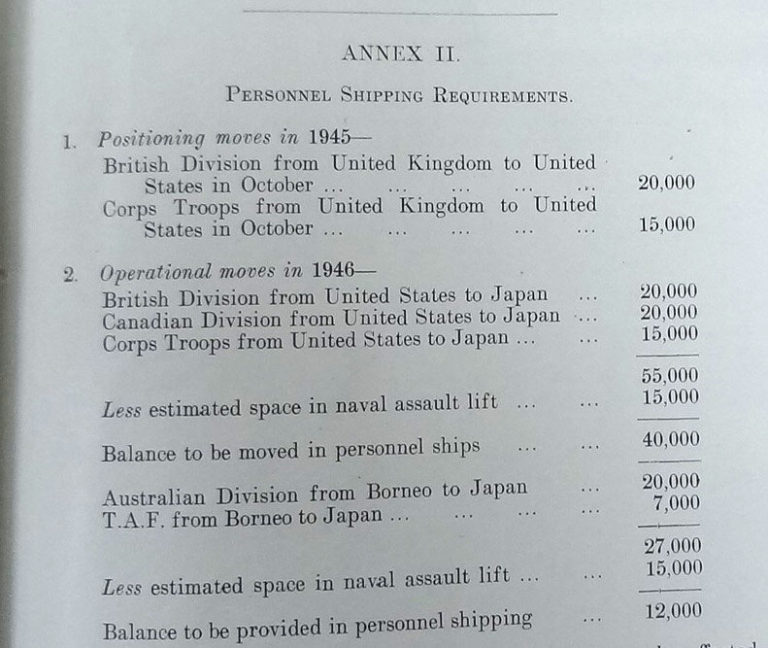

One British, Canadian, and Australian division was approved, with a smaller New Zealand contingent also earmarked for service, in a force that would eventually total 55,000. The Australian division would train and embark from Borneo, while the British and Canadian contingent were to be transported to the United States for training on 1 October 1945. The prevailing feeling was that ‘the passage of a British Division through the United States will have a good effect on United States public opinion’. Once in North America, the divisions would be re-quipped with American weapons in order to simplify supply lines once the operation had begun. British authorities had insisted, however, that the British division, at least, should be permitted to retain its own uniform.

After some debate, the British 3rdDivision was earmarked for service. This division had fought during the Battle of France, had landed on Sword Beach on D-Day, fought through the Battle of Caen, Operations Goodwood and Charnwood, and participated in operations across north-west Europe until VE Day. It was chosen because it was already a fully trained division and, officials admitted, ‘a small proportion may be left who took part in the assault on Normandy in June 1944’ (WO 193/825). Members were to be given 28 days leave before their date of embarkation and would realistically have spent the next six months in North America, before making its way to the Pacific.

Orders to that effect were to be issued to British Commonwealth land force Commanders of the ‘Coronet Force’ on 10 August 1945, a day after the second atomic bomb had been dropped on Nagasaki, and the Soviet Union’s declaration of war on Japan. By 15 August, Japan had surrendered, and this was formalised on 2 September when MacArthur accepted on behalf of the Allies on the USS Missouriin Tokyo Bay. British and Commonwealth forces, of course, were no longer required for the task they had begun to prepare for, but it is certainly interesting to think about what was being put in place had the atomic bombs not been dropped.

The atomic bombing of Hiroshima

Lessons Learned: Lori Karmel of We Take The Cake2024-05-20 01:42

9 Musts for a Competitive Edge in 2016, for Ecommerce2024-05-20 01:26

5 Signs of Conversion Leaks on Ecommerce Sites2024-05-20 01:04

Google Analytics Set-up Checklist for Ecommerce2024-05-20 00:44

Bloglist: Sean Schofield, Creator of Spree Ecommerce2024-05-20 00:05

10 Essential Google Analytics Dashboards for Ecommerce2024-05-20 00:02

5 Great Video Hosting Services for Ecommerce2024-05-19 23:39

3 Great Retailer Blogs Content Marketers Should Read2024-05-19 23:10

Avoid Credit Card Processing Proposals with AVS Fees2024-05-19 23:08

10 Google Analytics Reports that Show Where Your Store Loses Visitors2024-05-19 23:06

7 Ways to Improve a Customer’s Shipping Experience2024-05-20 01:29

4 Ways Google Analytics Produces Confusing Data2024-05-20 00:55

10 Last-minute Ways to Increase Holiday Conversions2024-05-20 00:33

Google Analytics Benchmarking Reports Return2024-05-20 00:12

How to Manage Tracking Tags on an Ecommerce Site2024-05-20 00:08

Drive Ecommerce Conversions with First-person Statements2024-05-19 23:19

7 Little Things to Improve an Ecommerce Business2024-05-19 23:15

3 More Tips for Better Ecommerce Video Results2024-05-19 23:15

Geolocation Helpful to Merchants, Tricky for SEO2024-05-19 23:01

Use Shopping Surveys to Increase Conversions2024-05-19 23:01