时间:2024-05-20 01:47:11 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

When one considers the formal conclusion of the war against Japan 75 years ago, within the popular i Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto ETF

When one considers the formal conclusion of the war against Japan 75 years ago,Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto ETF within the popular imagination two separate horrifying visions spring to mind, visions that have come to epitomise the manner in which the conflict in the Far East came to a close.

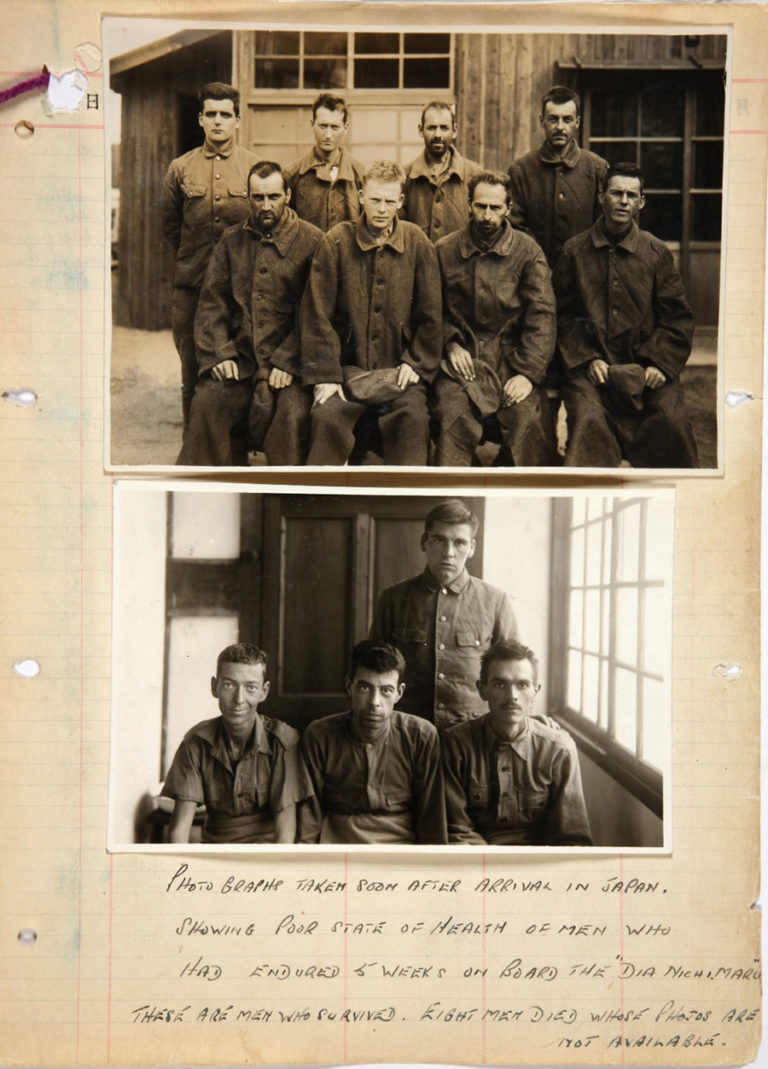

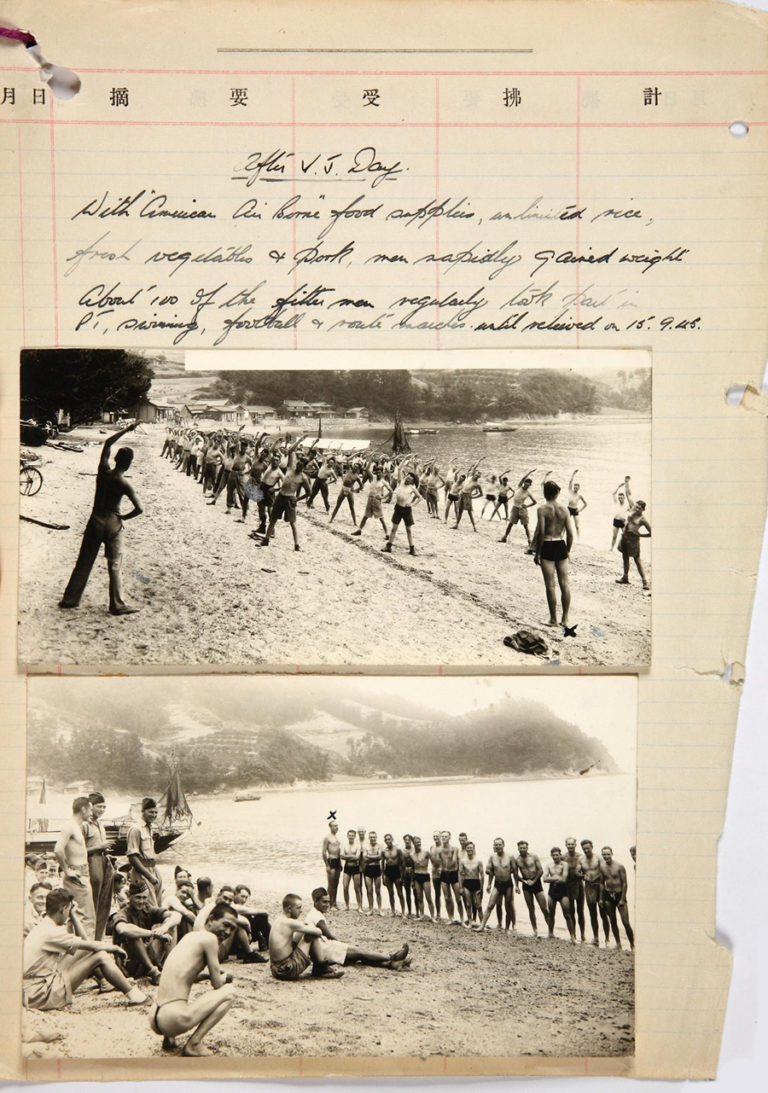

The first is of the atomic blasts which obliterated the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, wreaking untold devastation on the cities’ civilian populations, and leaving a terrifying legacy in their wake. The second is of the starving, emaciated and haunted-looking British and Allied prisoners of war who were liberated from three and half years of slavery and malnourishment. Few would associate both within the same setting.

However, so it was for many hundreds of Allied POWs who were incarcerated in labour camps dotted around the outskirts of both the Hiroshima and Nagasaki metropolitan areas. The National Archives hold photographs and handwritten accounts, specifically within AIR 49/384, which detail the conditions at one of these POW camps, Hiroshima Camp No. 2 on Innoshima Island, along with medical care afforded to its inmates. In addition, within ADM 223/168 is an extraordinary eyewitness account of the atomic explosion that destroyed Nagasaki, while ADM 1/17343 contains a very brief account of the two-man British medical mission which provided medical care to British POWs prior to their evacuation from the Nagasaki area.

According to the report drafted by Warrant Officer Fabel of the Army Education Corps, who arrived at the Innoshima Island POW camp from Hong Kong on 23 January 1943, he had found some 92 POWs already interned there. This included one Lieutenant-Commander of the Royal Navy, four officers and two Warrant Officers (WOs) of the RAF, along with around 85 RAF servicemen of ordinary rank. To this number, Fabel’s recently-arrived detachment added 100 prisoners, including 86 members of the Hong Kong Volunteer Defence Corps (HKVDC), a formation of mainly white British and Commonwealth civilian militiamen who were mustered to defend the colony from attack (AIR 49/384).

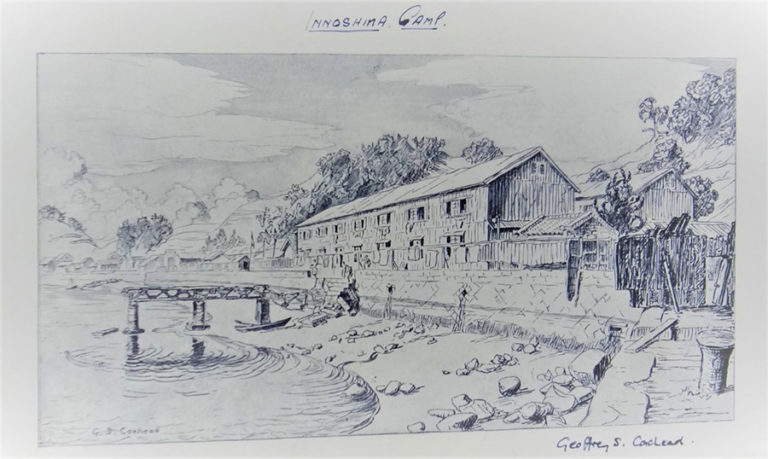

The Innoshima camp included two-recently constructed barrack buildings which faced out onto the Inland Sea and the adjoining Mitsubishi dockyard. From the account, it appeared that prisoners at this camp were accommodated relatively well in one of these buildings, which had seven double-tiered rooms, each holding 32 rice-straw pallet beds in wooden frames, called ‘tatamis’, with 16 on the ground floor and 16 in two galleries above. Each prisoner was given five blankets and officers and WOs were given straw mattresses for their beds. Fires in stoves were provided from December to March, while mosquito nets were allocated throughout May to September. Two rooms in a separate building were allocated for use as a hospital, and could accommodate up to twenty cases (AIR 49/384).

However, in spite of the apparently good conditions, all was not well for the inmates of Innoshima Camp. The conditions of work were tough, and food rations were not abundant. The majority of those hospitalised during their incarceration suffered from malnourishment, while others sustained severe injuries. The camp lacked a British medical officer, which was a major drawback as the word of such a figure could have proved key in saving sick and injured POWs from work. Instead, they received occasional visits from a Japanese medical officer and were fortunate to have the Habu Dockyard Hospital staff to call upon when necessary (AIR 49/384).

The Habu Dockyard was owned and run by the Osaka Iron Works Company. It was for this organisation that the inmates of Innoshima Camp, under the direction of Lieutenant (later Captain) Nomoto and his administrative staff, would labour from 1943. Fabel’s report would contain a detailed appraisal of all the medical treatment afforded to the prisoners of Innoshima, along with lists of medical supplies maintained, details of International Red Cross aid delivered to the camp, together with signed witness statements taken from POWs who sustained injuries during their time working at the dockyard (AIR 49/384).

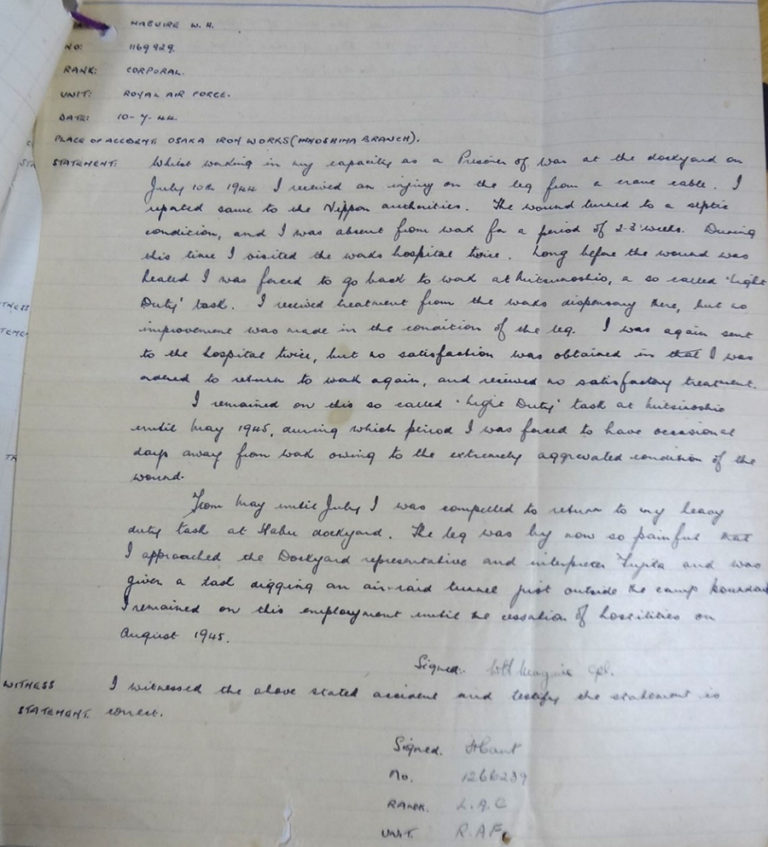

Leading Aircraftman (LAC) Maguire’s witness statement delivers a perfect example of the sufferings of injured POWs who were forced to continue working in spite of their wounds. Maguire received a wound to his leg from a crane cable at the Habu Dockyard on 10 July 1944, and the wound soon became septic. He was absent from work for 2-3 weeks, during which time he was twice able to visit the dockyard hospital. However, before the wound had healed he was sent to work carrying out so-called ‘light duty’ tasks at the Mitsubishi Dockyard near the camp. Although he received treatment from the dockyard dispensary, the condition of his leg did not improve, and despite two further visits to hospital, Maguire ‘received no satisfactory treatment’ (AIR 49/384).

Maguire would remain on ‘light duty’ tasks at the Mitsubishi dockyard until May 1945, by which time the severity of his leg wound had become increasingly aggravated. He was then compelled to return to his ‘heavy duty task’ at the Habu Dockyard, but the pain of his wound forced him to appeal to a dockyard representative through an interpreter named Fujita. Maguire was, instead, set to work digging an air raid tunnel just outside the camp. He would remain at this task until hostilities ceased in August 1945 (AIR 49/384).

Inevitably, many British and Allied POWs imprisoned in camps on the outskirts of Hiroshima and Nagasaki became eyewitnesses to the atomic explosions which obliterated both cities. One eyewitness account of the Nagasaki blast was circulated in a Weekly Intelligence Report produced by the Admiralty’s Naval Intelligence Division in November 1945. The source of the account was a Petty Officer of HMS Exeterwho had been a prisoner at Fukuoka Camp No. 11, four miles away from the blast epicentre (ADM 223/168).

The POW eyewitness was working alongside fellow prisoners, gardening on a hillside with a ‘ringside view’ of where the bomb exploded. At 10:58 hours on the morning of 9 August (erroneously recorded as 2 August) they watched a B 29 aircraft drop three parachutes over the target area, one large and two small. The larger parachute detonated 100 feet from the ground, emitting a blinding flash which, according to the eyewitness, ‘would have lit up the whole of England had it been dark instead of daylight’. The flash was so brilliant that it appeared to blot out the sun, and the heat emitted so intense that it held the eyes open for eight seconds, giving the eyewitness ‘the impression of being dangled in hell and hauled out’ (ADM 223/168).

According to the account, it took 22 seconds for the shockwave from the blast to reach the hillside where the POWs worked. They watched as four square miles of factories and houses went into the air and came down as dust and molten metal. Later they discovered that railway engines, a mile from the explosion and weighing 100 tonnes, were lifted from their rails and thrown 300 yards. In addition, the Mitsubishi steel works, one of the largest and most prominent manufacturing plants in the city, was razed to the ground and its metal superstructure melted in the heat. However, it is the description of the gigantic white cloud left behind by the explosion that proves to be the most terrifying aspect of this account (ADM 223/168):

‘About four minutes after the explosion a dense white cloud appeared over the target, a man-made cloud of terrific density, so dense that smoke from thousands of fires created by the bomb could not penetrate it, but arose in huge columns in outer extremities of this pure white cloud.

A little later, looking through a pair of common sun-glasses at the cloud, colours appeared that I have never seen before; it looked like a giant catherine wheel, only very slowly revolving and milling, green merging into purple and reappearing as blue as Arctic ice pack, only to disappear and reappear as blood red’ (ADM 223/168).

On 8 September 1945, six days after the formal surrender of the Imperial Japanese government aboard the USS Missouriin Yokohama Harbour, two Royal Navy Surgeon Lieutenants named Cotsell and Cardew disembarked at Yokohama from HMS Indefatigable. They would spend 20 days in Japan; their mission was to provide medical attention to repatriated POWs and oversee their safe evacuation from the country. Much of their activities would be carried out at Nagasaki harbour where thousands of former Allied POWs, most of them British, were brought for processing, medical examination and treatment, followed by embarkation (ADM 1/17343).

The two Royal Naval medical officers worked alongside colleagues in the United States armed forces under the direction of Colonel Griffin of the US Army and Captain Parsons, the Principal Medical Officer of the US Navy Hospital Ship Haven. From 14thto 17thSeptember, they worked with American medical officers to process trainloads of former POWs, numbering on average between 600 and 1,000, which passed through daily. The reception of these POWs, as Cotsell and Cardew observed in their report, was most efficient, and British servicemen were ‘pleased’ to see the Royal Navy uniforms among the host of American uniforms which greeted them upon arrival. In addition, each train which rolled into the station was met by a brass band playing the appropriate tunes: ‘for the benefit of the British lads, “Tipperary”’ (ADM 1/17343).

Stretcher cases, skipping the normal procedure, went straight aboard the USS Haven, while walking cases were given coffee and doughnuts as clerical staff filled out both Army and medical forms. Once processed, each case was put through a shower and sprayed with D.D.T. (for malaria and typhus), before being issued with a new set of clothes and ‘toilet gear’. After 18 September, Captain Parsons suggested that Cotsell and Cardew should work on the 80-bed ward on board the Haven, a proposal accepted by both officer. They would remain at this post until their departure from Nagasaki on 23 September (ADM 1/17343).

During their period on the hospital ship, they learned that 30 per cent of the ex-prisoners who arrived at Nagasaki had been admitted to the Haven, suffering mainly from malnutrition and avitaminosis (severe vitamin deficiency). This was remedied through ‘a balanced diet and large doses of vitamins’, administered either orally or parenterally. Thiamine, administered by injection, was discovered to be especially effective in the treatment of both malnutrition and Beri Beri (ADM 1/17343).

Cotsell and Cardew also reported that a great number of cases admitted to Haven were prisoners suffering from tachycardia (accelerated heart rate, exceeding the normal resting rate), which was identified by both officers as possibly resulting from overindulgence in caffeine and nicotine; the majority of prisoners had undergone a sustained abstinence from both substances for more than three years. There was one death among all the cases admitted to USS Haven. This former POW suffered a cardiac arrest and died after overeating following a severe case of Beri Beri (ADM 1/17343).

This death, along with the nature of many of the cases admitted to the Haven, underlines the poor state of health in which many of these former prisoners were found by Allied medical staff at Nagasaki port. This, invariably, points to a prolonged period of abuse and maltreatment at the hands of their captors. The choice of Nagasaki as one of the main ports for the processing of repatriated Allied POWs, in view of devastation recently inflicted upon the city, whether by accident or design, is somewhat symbolic of the two tragedies which came to mark the end of the war against Japan. A shattered city which became a place of healing for shattered men.

10 Mobile Shipping Apps for iPhone, BlackBerry and Android2024-05-20 01:23

Should Online Retailers Offer Senior and Military Discounts?2024-05-20 00:32

7 Overlooked Holiday Tactics for Amazon Sellers2024-05-20 00:29

Credit Card Processing: Detailed Statements Essential for Merchants2024-05-20 00:09

Lessons Learned: Bicyclinghub.com Owner Doug Duguay2024-05-19 23:57

Yahoo Introduces Live Store Badges to Help Build Trust2024-05-19 23:40

10 Text Messaging Tools for Local Business Marketing2024-05-19 23:38

Getting Sales Tax Setup Right on Amazon2024-05-19 23:21

Interview: Authorize.Net President On Fraud Prevention2024-05-19 23:19

Lessons from changing ecommerce platforms2024-05-19 23:08

Quick Query: Internet Attorney John Dozier on eCommerce Law2024-05-20 01:46

USPS Regional Rate Shipping Saves Money2024-05-20 01:40

Credit Card Processing: Detailed Statements Essential for Merchants2024-05-20 01:39

What’s the True Cost of Inventory?2024-05-20 01:32

Lessons Learned: Best Bully Sticks Thrives on Teamwork2024-05-20 01:18

3 Ways to Build B2B Relationships with Ecommerce2024-05-20 00:56

Using Facebook Ads for B2B Targeting2024-05-20 00:52

‘Internet of Things’ Helping Ecommerce Merchants2024-05-20 00:44

Legal: Ecommerce Owners Liable to Patent Trolls?2024-05-20 00:02

Local SEO Ranking Factors for Multi-location Businesses2024-05-19 23:30