时间:2024-05-20 01:44:15 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Warning: This blog post contains potentially distressing text and images.You may not have heard of N Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Margin Trading

Warning: This Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Margin Tradingblog post contains potentially distressing text and images.

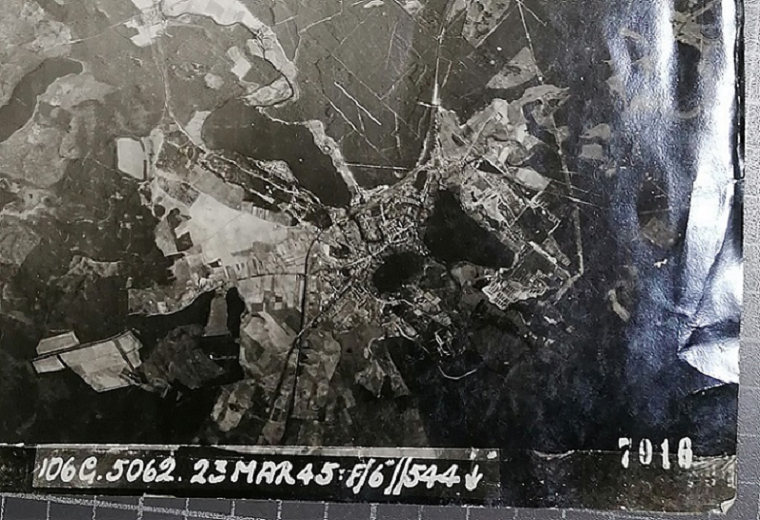

You may not have heard of Neuengamme, near Hamburg, in the north of Germany. Established in 1938, it was built by the prisoners themselves, and had close to 90 satellite camps, known as Aussenkommandos.

This year, the theme for Holocaust Memorial Day is ‘One Day’. Looking at the records we hold relating to the Neuengamme concentration camp, I found it difficult to pick a day. I tried to pick several days, but again found it impossible and therefore didn’t do it. How do you decide what to select when every day was much the same as the one before and the one after?

My intention is not to provide a history or a catalogue of the sufferings endured in the camp. I hope, however, that I will be able to give those who have never heard of Neuengamme an idea of what was happening there, and why it gained the reputation of being ‘among the worst of the concentration camps in Germany’ (WO 309/1592).

According to the death register, at least 42,900 prisoners died in the camp. It is only an estimate. All the records were burnt by the SS, and it was bit by bit, like a monstrous jigsaw puzzle, that the enormity of what had happened in Neuengamme started to emerge.

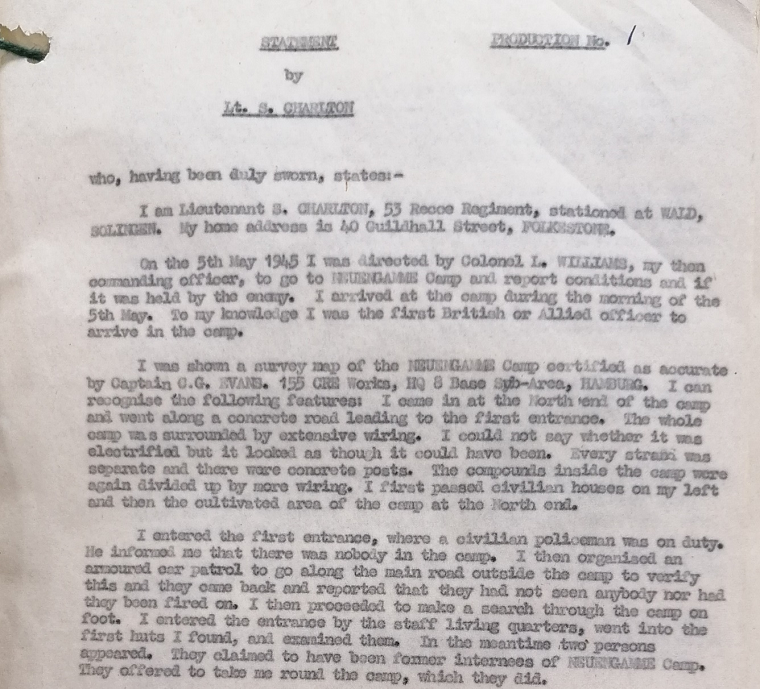

Sent by his commanding officer to investigate reports of a nearby prisoner camp, Lieutenant S Charlton, of the 53 Reconnaissance Regiment, arrived in Neuengamme on 5 May 1945. Several concentration camps had by then been liberated, and he must have been bracing himself for the worst. He found the camp completely empty, with a civilian policeman guarding the entrance.

The camp had machine gun posts and look out towers. He wasn’t sure whether the wiring was electrical, but it ‘looked as if it could have been’. As he was inspecting barracks, ‘two persons appeared’. These two former prisoners offered to guide him through the camp and explained the purpose of the different buildings.

‘To anybody who did not know about it,’ Charlton said of one of these buildings, ‘it appeared to be a butcher’s shop or a dairy’. It was a ‘medical experimental station’. The place appeared to have been thoroughly cleaned, and he only found ‘rubber gloves and what [he] took to be a preserved human heart in a bottle’

Charlton spent four days in Neuengamme before handing over to ‘Corps Representatives who were organising it into a PoW camp’ (WO 309/872).

The phrase ‘extermination through labour’ – ‘Vernichtung durch Arbeit’ in German – was reportedly coined by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi propaganda minister, in 1942. On opening the trial in 1946, Major S M Stewart, one of the prosecutors, noted: ‘the phrase in its conciseness and in its form with all its horrifying implications is Dr Goebells [sic] at his best’ (WO 235/162).

At the beginning, prisoners were routinely murdered in Neuengamme. In 1942-1943, for instance, some 1,000 Russian prisoners with TB were injected with phenol, and, in the autumn of 1942, 197 were gassed with zyklon B. It all changed after the heavy losses suffered by Germany at Stalingrad. More manpower was needed to support the war effort.

From then on, Neuengamme functioned as a sort of clearing station, sending manpower to the satellite camps, and killing off those who were too weak or sick to work.

Prisoners worked 10 hours a day in inhumane conditions, and it was usually heavy work. In the Husum Aussenkommando, for instance, they dug anti-tank ditches in heavy, sodden marshland. Others worked in weapon factories, mines, shipyards, building sites or on the railways. Numerous statements describe their ‘almost complete absence of footwear’ and ‘scanty clothing’ (WO 309/872).

Paul Aage Jens Thygesen, a Danish prisoner who had arrived in Neuengamme in September 1944, worked in Husum. He kept sickness and mortality records, which he later managed to smuggle back into Neuengamme, ‘hidden in [his] rectum’. On 25 November 1944, out of 1,000 prisoners, 734 were sick, mostly with intestinal diseases (WO 309/790).

Tadeusz Kowalski, a Polish prisoner-doctor at Neuengamme, first worked as an orderly, then as a doctor in the tubercular department. He stated that prisoners mostly died of weakness. During the trial, it was noted that doctors in the camp ‘were expected to salvage those patients from whom more work could be obtained’. However, conditions in the hospital were so squalid, with three men, sometimes more, sharing a berth and all diseases put together, a blatant lack of medicines and the constant threat to be sent back to hard labour, that there was little hope of recovery. ‘The SS doctor,’ Kowalski recalled, ‘was not concerned with treatment at all. He occupied himself only with releasing patients’ (WO 235/162).

Prisoners had to work until they simply couldn’t. Then, they were sent on to other camps to be exterminated, usually Bergen-Belsen, Auschwitz or Majdanek.

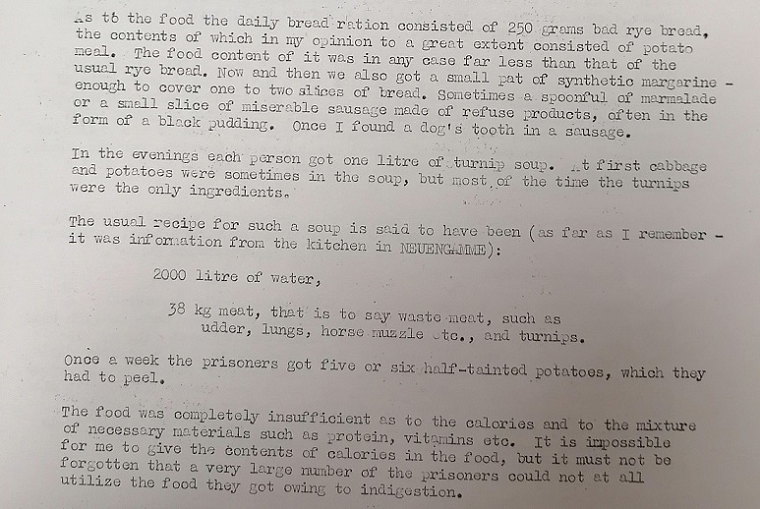

While visiting the camp, Lieutenant Charlton came across large dumps of turnips, which seemed to have been the basis of the prisoners’ diet. Hunger was a constant torture, and many of the prisoners were too sick to eat what little food they were given.

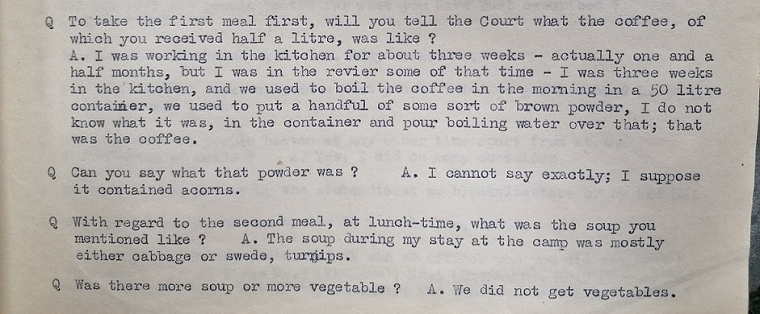

According to statements, there were three meals a day. In 1944, breakfast consisted of 1/3-1/4 litre of ersatz coffee or thin soup and just below 110g of bread (‘1/14 loaf of bread of 1,500g’). Lunch was 1.5 litres of watery soup. Dinner was about 250g of bread, 1/3 litre ersatz coffee, 10-20g margarine, and 60g sausage or fish paste, or unpeeled potatoes – or jam, on Sundays (WO 309/1592).

Thygesen recalled: ‘once, I found a dog’s tooth in a sausage’. He said the soup was made of water and waste meat (‘udder, lungs, horse muzzle’) and turnips. Most of the time, it was only turnips (WO 309/790).

Phillip Jackson, who was 16 when he was arrested in Paris with his parents for being part of a resistance network, worked briefly in the kitchen at Neuengamme. He said they were also sometimes given noodles on Wednesdays. He also explained, during the trial, that the ‘coffee’ they were given was probably some sort of acorn-based powder.

There was a special ration for heavy workers, but at an additional 250g bread and 3g margarine, it was grossly inadequate. Along with hard labour, starvation was part of the ‘extermination through labour’ Nazi strategy to kill off prisoners without using up any additional resources.

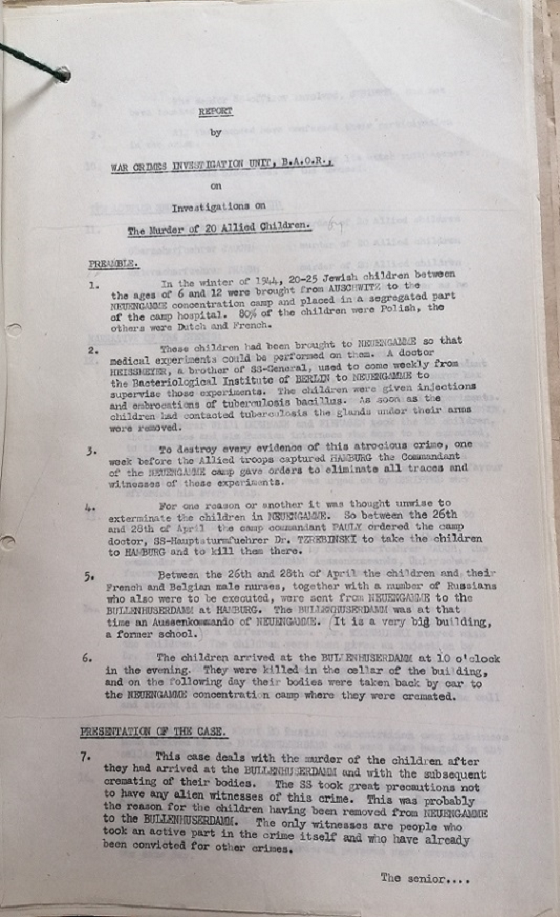

Kurt Heissmeyer was an SS doctor. He wanted a professorship and, to obtain one, had to produce original research. His theory was that the injection of live tuberculosis bacilli would act as vaccination. He practiced experiments on adults in Neuengamme, then requested children.

Twenty Jewish children, ten boys and ten girls, were transferred from Auschwitz at the end of 1944. When they arrived, they were healthy, bar one, suspected of having TB. ‘They were cheerful, perfectly normal, children’.

Looked after by French doctors Prof Gabriel Florence and Dr René Quenouille and Dutch orderlies Dirk Deutekom and Anton Hölzel, the children were subjected to abject experiments in a barrack called ‘Sonderabteilung Heißmeyer’ (Heissmeyer Special Unit). Heissmeyer cut small incisions under their arms and rubbed TB in. He also used lung probes to inject the disease more deeply. Florence tried to kill off the TB bacilli by boiling them before the children were injected, but they all fell ill.

Heissmeyer had regular X-rays performed to monitor the progress of the disease, and had their armpit lymph nodes surgically removed for examination (WO 235/162).

Kowalski reported: ‘On the 18thApril 1945 all the children were taken away, along with the doctors’ (WO 309/872). It was actually on 20 April that the children and their carers arrived at the Bullenhuser Damm, an old school building. The carers were hanged straight away.

Mania, Lelka, Sergio, Surcis, Riwka, Eduard, Alexander, Marek, Walter, Lea, Georges-André, Bluma, Jacqueline, Eduard, Marek, H., Roman, Eleonora, R., and Ruchla were given morphine injections by Neuengamme’s Chief Doctor, Alfred Tzrebinski, before being hanged. Johann Frahm, the Bullenhuser Damm blockleader, stated on 2 May 1946: ‘A rope was placed on their neck and, like pictures, they were hanged on hooks on the wall’ (WO 309/872).

Testifying on 3 July 1946, within the frame of a follow-up trial devoted to the Bullenhuser Damm murders, Max Pauly, the Commandant of Neuengamme, stated: ‘the 20 children were executed because they had been experimented on, and the nurses, because they had watched the experiments’. Just like the records the SS burnt before the evacuation of the camp, they were embarrassing witnesses.

Heissmeyer, in case you’re wondering, wasn’t arrested straight away. After the war, he went back to Magdeburg and was a successful TB specialist under his own name, until his atrocities finally caught up with him at the end of the 1950s. He was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment in 1966. He died a year later.

In the words of the investigators, ‘this murder is outstanding for its utter ruthlessness and for the cold bloodiness of the accused’.

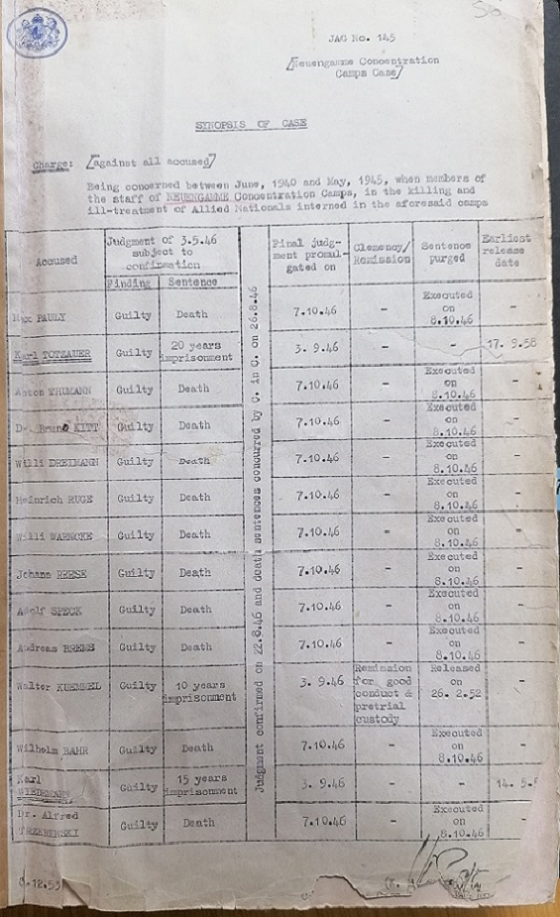

The trial of 14 men who had held leading positions in the main camp at Neuengamme opened on 18 March 1946. Held at the Curio Haus in Hamburg, it lasted until 3 May. Over the next two years, 33 trials relating to Neuengamme and its satellite camps would be held, bringing 99 men and 19 women to justice.

The 14 accused were charged with committing a war crime. According to the proceedings, ‘each (…) pleaded Not Guilty and each was found Guilty’ (WO 235/659).

Giving a statement in Copenhagen on 16 March 1946, Paul Aage Jens Thygesen highlighted the

‘systematic starvation (. . .), the strong psychical pressure which constantly weighed upon the prisoners, the terrible housing conditions (. . .), hard labour (. . .) and above all: the camp leaders’ complete incompetence and lack of respect for the most elementary human necessities and conditions of life’ (WO 309/790).

Eleven of the accused were sentenced to death by hanging, the other three to long prison sentences.

Unexpectedly I found out that a member of my own family died during the evacuation of Neuengamme and its Aussenkommandos. Today, as we remember the victims of Nazi atrocities, and like every time I think about concentration camps, I am grateful. Grateful to him, to my great-grandmother and to all the men and women who fell victim of the camp system, whether civilian or military, whatever their faith or politics. I am grateful for their sacrifice, their resilience and the constant reminder not to take humanity for granted.

Crowdfunding: 5 Things You Should Know2024-05-20 01:29

3 Keys to Exporting: Fulfillment, Language, Payment2024-05-20 01:09

Quick Query: Work-at-home Mom Runs CandlesAndSuch.com2024-05-20 00:57

Lessons Learned: Micheline Hellwege of The Collector’s Hub2024-05-20 00:03

Quick Query: ArtQuiver.com Delivers Original Art With Lifetime Guarantee2024-05-19 23:53

Ecommerce Know-How: Sole Proprietorship, S Corporation or LLC?2024-05-19 23:44

Quick Query: Covario’s Stephan Spencer on Mobile Commerce2024-05-19 23:29

The PeC Review: Filtrbox for Reputation Management2024-05-19 23:21

Credit Card Fraud: How Big Is The Problem?2024-05-19 23:07

What Is a Denial-of-Service Attack?2024-05-19 22:57

How to Pack and Protect an Ecommerce Shipment2024-05-20 01:26

CyberSource CEO Addresses Visa’s Acquisition2024-05-20 01:05

Authorize.Net Exec Offers Fraud Prevention Tips2024-05-20 00:20

Quick Query: Covario’s Stephan Spencer on Mobile Commerce2024-05-20 00:12

Sales Tax: Frequently Asked Questions2024-05-20 00:05

Legal: Privacy Lessons from the Twitter Breach2024-05-19 23:56

The PEC Review: Shipwire Fulfillment Services2024-05-19 23:23

Free Shipping: The How-to Economic Model2024-05-19 23:21

38 Fees and Surcharges from FedEx and UPS2024-05-19 23:05

Quick Query: Covario’s Stephan Spencer on Mobile Commerce2024-05-19 23:01