时间:2024-05-20 04:04:42 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

This blog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events f Ryan Xu hyperfund Crypto Margin Trading

This Ryan Xu hyperfund Crypto Margin Tradingblog article is part of the 20sPeople season – a season of exhibitions, activities and events from The National Archives that explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s.

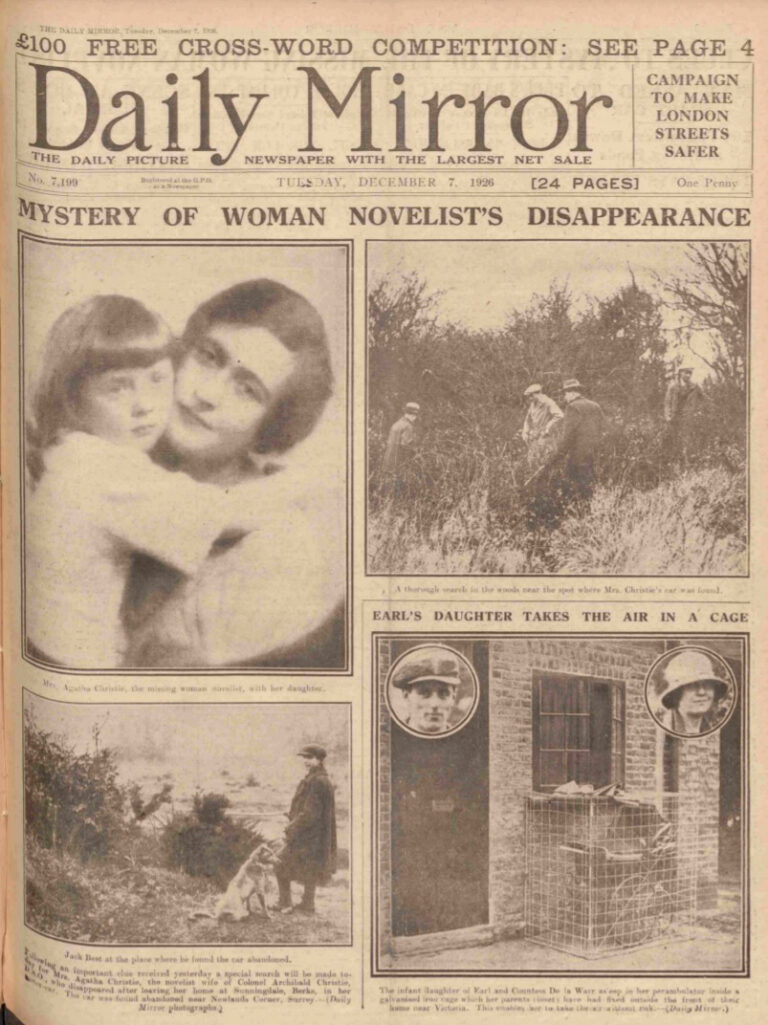

With today’s release of the new film adaptation of Agatha Christie’s 1937 novel, Death on the Nile, I’m taking another look at one of the most bizarre events in the famous crime novelist’s life. On the evening of Friday 3 December 1926, Agatha Christie left her home in Sunningdale, Berkshire, got into her car and disappeared into the night. Her disappearance sparked a manhunt involving the police, members of the public and famous figures and was lapped up by the tabloid press. This strange series of events was worthy of her own works of fiction; however, unlike the mysteries solved by Hercule Poirot or Miss Marple, this one was never fully explained. Records held at The National Archives give us a unique insight into the strange events of December 1926.

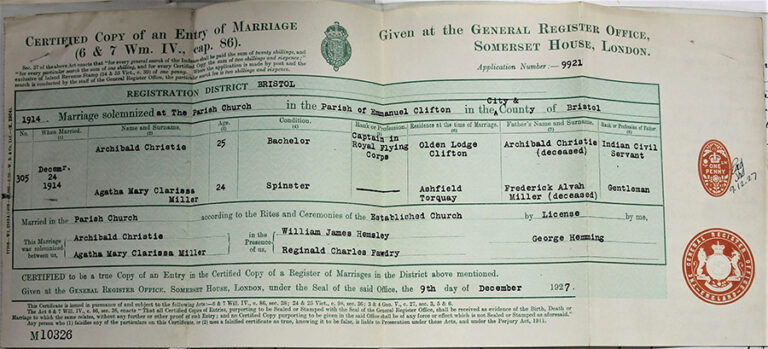

Agatha Christie’s career was at its height at the end of 1926. Her sixth novel, The Murder of Roger Ackroyd, had been published earlier that year and her first collection of short stories featuring the character of Hercule Poirot had been published two years previously. Christie’s personal life was less happy, however. Her husband Archibald Christie (Archie) had been having an affair with a woman called Nancy Neele and in August, he asked Agatha for a divorce. Following an argument between husband and wife on 3 December, Archie left to spend the weekend with friends. Later that night Agatha kissed her daughter Rosalind goodnight as she lay sleeping, left the house and drove away in her Morris Cowley. The next day, the car was discovered abandoned above a chalk quarry at Newlands Corner, and some of her clothes were found inside. The police reported that:

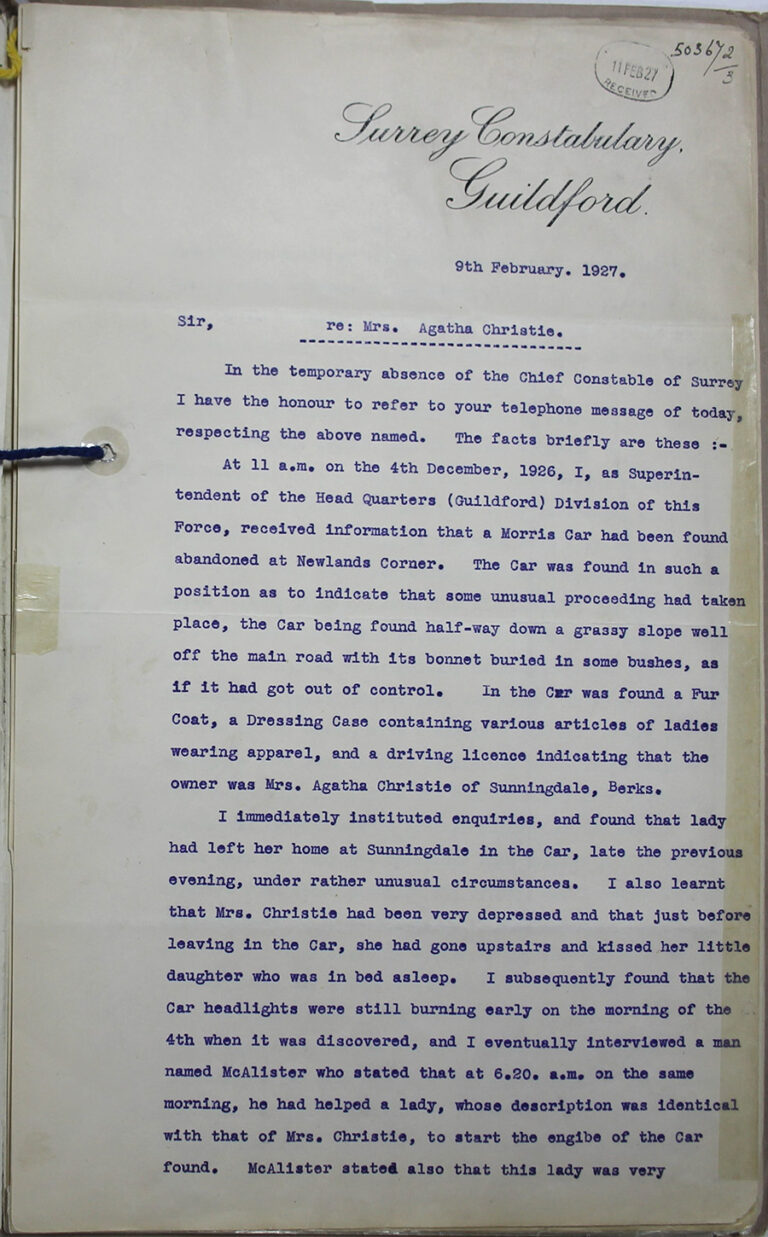

‘The car was found in such a position as to indicate that some unusual proceeding had taken place, the Car being found half-way down a grassy slope well off the main road with its bonnet buried in some bushes, as if it had got out of control. In the Car was found a Fur Coat, a Dressing Case containing various articles of ladies wearing apparel, and a driving licence indicating that the owner was Mrs. Agatha Christie of Sunningdale, Berks.’

The National Archives, Agatha Christie: search by police and civilian volunteers when her car was found abandoned, 1927. Catalogue ref: HO 45/25904

Many assumed the worst, and a police investigation began to find the missing woman. A man who had seen Agatha Christie that night reported that she was ‘sparsely dressed for such an inclement morning, and that she appeared strange in her manner.’ 1

The disappearance was also widely reported in the newspapers, and concerned members of the public joined the search. Journalists put forward a range of theories to explain her disappearance. Some suggested she had drowned herself, others that she had been murdered by her husband. And still others claimed the whole turn of events was nothing more than a publicity stunt to promote her novels. Some prominent figures joined the efforts to find her. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who was a keen spiritualist, even consulted a medium to attempt to solve the mystery of her disappearance. 2

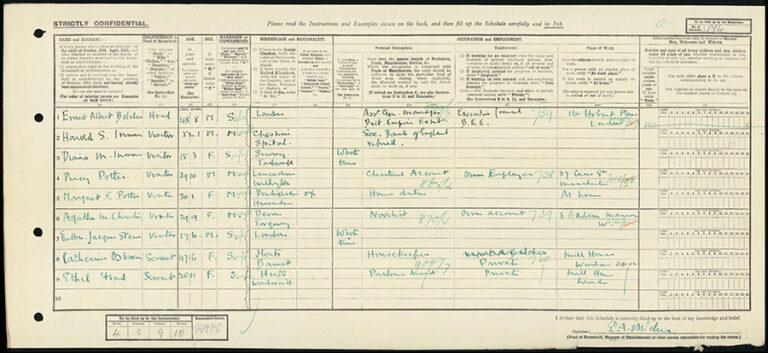

Finally, 11 days later on the 14 December, a member of the public recognised her staying at the Swan Hydro hotel in Harrogate. She had checked in under the name of her husband’s mistress. She was suffering with memory loss and could give no account of the preceding 11 days or any reasons for her actions. Her biographer Andrew Norman argues that she was in a ‘fugue’ state caused by trauma or depression 3; however, others still believed that her actions were deliberate and perhaps designed to cause distress and embarrassment to her husband.

Following Christie’s reappearance, there were concerns in some quarters that the police response had been excessive and that time and money had been wasted on the search for her. This was partly due to inaccurate press reports that aeroplanes, divers and multiple police forces had been involved. On 25 February, Mr Neil Maclean, MP for Glasgow Govan, put a question to the Home Secretary asking for information on ‘the number of the Metropolitan police specially detailed for the search for Mrs Agatha Christie; the time occupied; and the total cost, including the wages of the officers so detailed.’ 4

Documents relating to this question can be found in a Home Office file held at The National Archives. The written answer from the Home Secretary was that ‘No members of the Metropolitan Police were specially detailed for the purpose, and no cost was incurred by the Metropolitan Police. A description of the missing person was published in Information in the usual way.’ 5

This response was informed by a letter from the Deputy Chief Constable of the Surrey Constabulary, William Kenward, dated 9 February 1927. In it, he detailed the actions taken by the police in response to the disappearance and made clear that press reports had exaggerated the actual police response.

‘The number of police said to have been engaged has been greatly exaggerated, and I received invaluable assistance from the public generally. The aeroplanes which are said to have taken part in the search are nothing to do with the police. There is no doubt that a good deal of press matter circulated in connection with the case was without foundation.’

He also explained why the actions taken were justified by the potential danger that the missing woman could have faced following her disappearance.

‘The lady disappeared under circumstances which opened out all sorts of possibilities – she might have been wandering with loss of memory over that vast open country around Newlands Corner, or she might have fallen down one of the numerous gravel pits that abound there and are covered in most instances with undergrowth and lying helpless in agony, or she might have been as was strongly suggested to the police, the victim of a serious crime. Under no circumstances could the police of this district have justified any inaction in the matter.’

Agatha’s husband, Archie Christie, responded to enquiries about his wife’s state of mind by explaining that she was suffering from a nervous disorder and memory loss. The police approached him to request a contribution towards police costs, but he refused saying it was ‘entirely a police matter’. 6

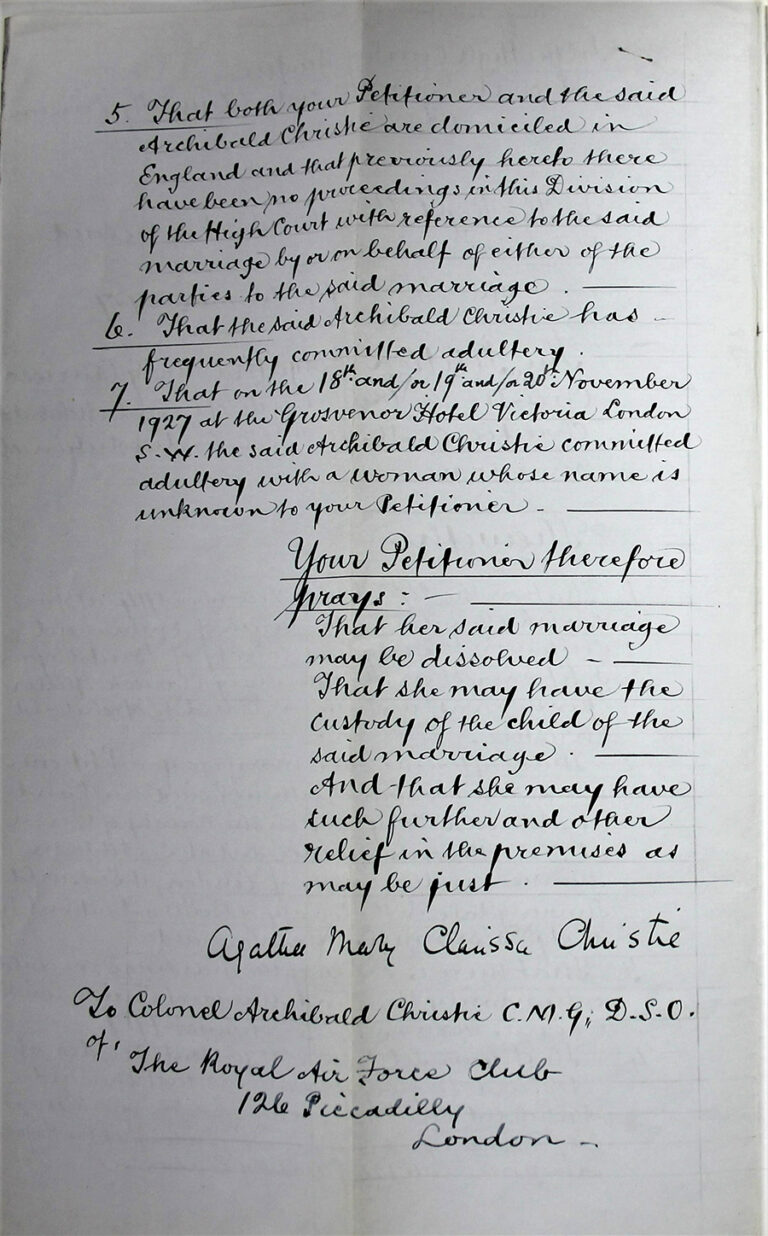

It may never be known whether Agatha Christie’s disappearance was due to the psychological effects of the depression she was suffering from, or whether there were other reasons. However, the breakdown of her marriage to Archie Christie was no doubt a traumatic experience. The couple finally divorced in 1928 and Archie went on to marry his mistress, Nancy Neele.

The sudden disappearance of Agatha Christie in December 1926 gave the British public a real-life taste of the kind of mystery she had shared with them in her stories. And this probably explains why the incident caught the imagination of so many at the time.

Despite this dramatic episode in her life, Agatha Christie went on to continued success in crime fiction, going on to publish over 60 more novels and numerous short stories. She is still today the best-selling novelist of all time, having sold over a billion copies of her books in the English language 7. Her wonderful stories, along with their many television and film adaptions, have brought joy to millions around the world.

20sPeople at The National Archives explores and shares stories that connect the people of the 2020s with the people of the 1920s. Accompanying the release of the 1921 Census of England and Wales, 20sPeople shows what we can learn by connecting with those who have gone before us. Find out more at nationalarchives.gov.uk/20speople.

Notes:

Jason Keenan, Media Advisor with ICANN2024-05-20 03:57

The SEC Asks Public Companies for Climate Info2024-05-20 03:53

Charts: Ecommerce in the Middle East (Stats, Outlook)2024-05-20 03:41

Charts: Retail Industry Outlook 20222024-05-20 03:12

How to Monitor and Manage Your Wholesale Suppliers2024-05-20 02:23

Charts: Global Parcel Shipping Volume, Transit Times2024-05-20 02:16

Charts: B2B Buyers Prefer Ecommerce2024-05-20 02:08

How the Ukraine War Impacts Ecommerce2024-05-20 01:49

Ecommerce Know-How: Taking Advantage of Online Education Opportunities2024-05-20 01:35

The Beauty of Bootstrapping a Business2024-05-20 01:26

Field Test: Order Management Software2024-05-20 03:18

Charts: Global Venture Capital Funding 20212024-05-20 02:38

Take a Side in the Future of the USPS2024-05-20 02:21

SEO: Amazon Keyword Research Tools2024-05-20 02:10

Miva Merchant President Discusses eBay, Facebook2024-05-20 02:03

Charts: Global Retail Tech Funding 20212024-05-20 01:59

Will Web3 Change Ecommerce?2024-05-20 01:55

The SEC Asks Public Companies for Climate Info2024-05-20 01:32

How to Make Your Customer Service Shine2024-05-20 01:21

Charts: Supply Chain Disruption Worldwide, U.S.2024-05-20 01:19