您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >Planning the burial of the Unknown Warrior 正文

时间:2024-05-20 03:24:06 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

‘Every precaution must be taken to ensure that his identity shall never become known.’On Friday 15 O Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Cross-chain

‘Every precaution must be taken to ensure that his Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Cross-chainidentity shall never become known.’

On Friday 15 October 1920, a mere 27 days before Armistice Day, the British Cabinet considered a proposal sent by the Dean of Westminster, Herbert Ryle. He had suggested that ‘the remains of one of the numerous unknown men who fell and were buried in France should be exhumed, conveyed to England, cremated if necessary, and given an imposing military funeral in Westminster Abbey on November 11th’.

After a lengthy discussion, in which the Chief of the Imperial General Staff declared that the Army would be unanimously in favour of the proposal, the Cabinet agreed, and plans were swiftly put into motion to make sure that this plan would come to fruition (WORK 20/1/3).

Records held at The National Archives shed light into this last-minute planning, and how the interment of the Unknown Warrior would coincide with the unveiling of the new permanent Cenotaph in Whitehall. After overcoming objections that this type of event would be deemed as ‘sensational’, the view was taken that such a gesture would be acceptable to the people, honour fighting men, and do so ‘without singling out for such distinction any one known man’. Arrangements were made for the selection of the individual and plans put together for their transportation to London.

The ship chosen to take the coffin of the Unknown Warrior from Boulogne to Dover was HMS Verdun. The vessel was specially selected to perform this duty as a compliment to France, given the significance of the Battle of Verdun to the French people.

As late as 6 November, the Admiralty notified the Commanding Officer of the vessel that ‘Their Lordships have selected HM Ship under your command to convey a coffin containing the remains of an Unknown Warrior…on November 10th’. The letter went on to provide instructions as to how the coffin was to be treated:

‘The coffin is to be received on board HMS Verdun by a seaman guard of about 20 men under an officer, and placed on a bier [pedestal] in a suitable position. A large Union Jack is to be taken to cover the coffin from Boulogne to London. Colours to be half-masted as the coffin arrives on board. The ship’s company is to be fallen in. After arrival on board, sentries with arms reversed are to be posted round the bier’(WO 32/3000).

Upon its arrival in Dover, the military garrison there was also given further instructions as to the procedure to be adopted. Once HMS Verdunhad passed through the entrance of the Harbour, a 19-gun salute would be fired by No.11 Fire Command, Royal Garrison Artillery (RGA).

The vessel was to come alongside No.3 berth, and was to be met by the band of the 2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers, which would be playing ‘Land of Hope and Glory’. The coffin would then be conveyed to the railway carriage, bound for London Victoria Station, by six bearers, one man from each of: the Royal Navy; No.11 Fire Command, RGA; 2nd Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers; 2nd Battalion, Connaught Rangers; Royal Marines; and Royal Air Force. Guards of honour, consisting of 3 officers and 100 other ranks, from the two Irish regiments stationed at the Dover Garrison, as well as students from the Duke of York’s Royal Military School, would then line the route through the town. The band was to play a slow march while the coffin was carried to the railway platform (WO 32/3000).

The coffin was to be placed in a luggage van, the same van which had carried the bodies of Edith Cavell, a nurse executed in 1915 for helping Allied service personnel escape in occupied Belgium, and Captain Charles Fryatt, a Merchant Navy Captain who was executed in 1916, having attempted to ram a U-boat off the Netherlands coast in March 1915. It would arrive at Victoria Station by the afternoon of the 10th.

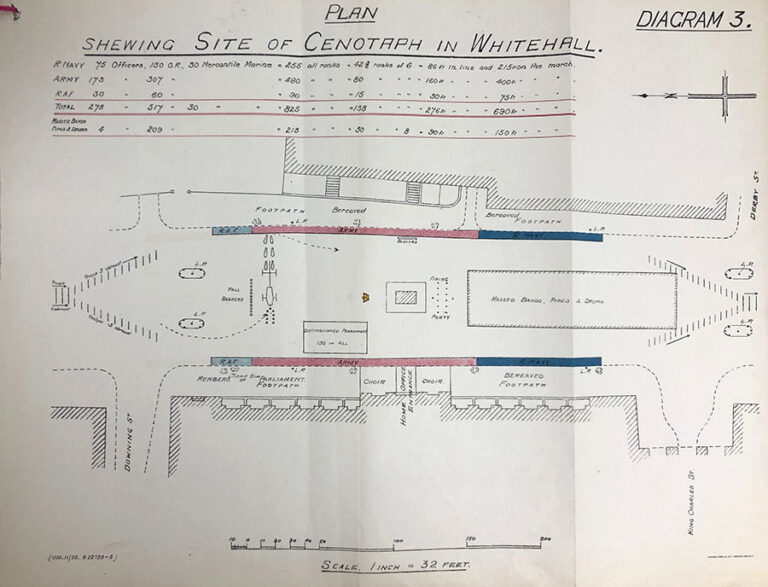

The event at Westminster Abbey was also to coincide with the unveiling of the permanent Cenotaph at Whitehall. A temporary memorial had initially been built, but the Cabinet had authorised Sir Edwin Lutyens to create an exact replica on the same site as the original at an estimated cost of £10,000, ‘in order that on the day of the Peace Procession the Nation should visibly express the great debt which it owes to those who, from all parts of the Empire irrespective of their religious creeds, had made the supreme sacrifice’ (WORK 20/139).

Though initially saying that he would not unveil the memorial (because of fear this would appear too ostentatious), following a groundswell of public feeling, the King agreed to perform the unveiling ceremony (WORK 20/1/3).

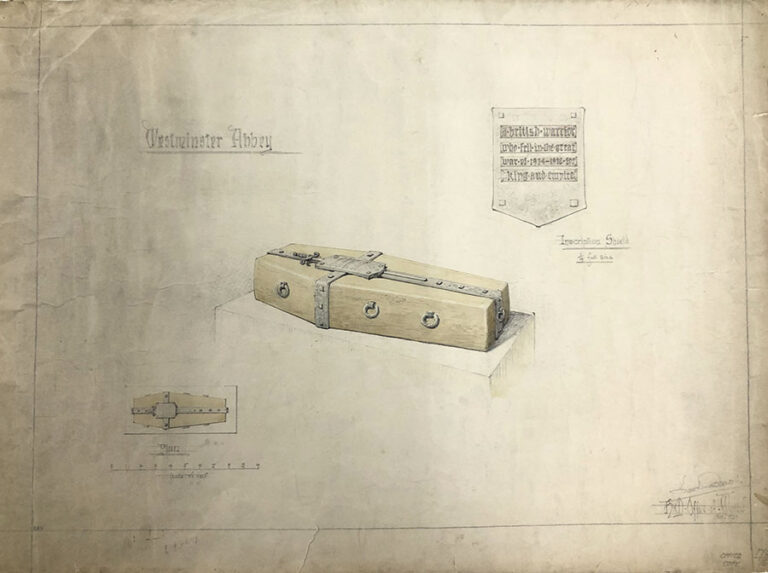

By 2 November, the Memorial Services Committee had decided that ‘the remains to be interred in the Abbey shall be those of an unknown British fighting man, and every precaution must be taken to ensure that his identity shall never become known’ (WORK 20/1/3). This broadened the initial proposals, when discussion had focused on the selection of, specifically, the bones of a soldier (they were not to be cremated – though this suggestion was in the Dean of Westminster’s initial proposal) who had fallen in 1914, and not just at any time in the war. This was even the preliminary recommendation made by the Cabinet, before the definition was subsequently broadened.

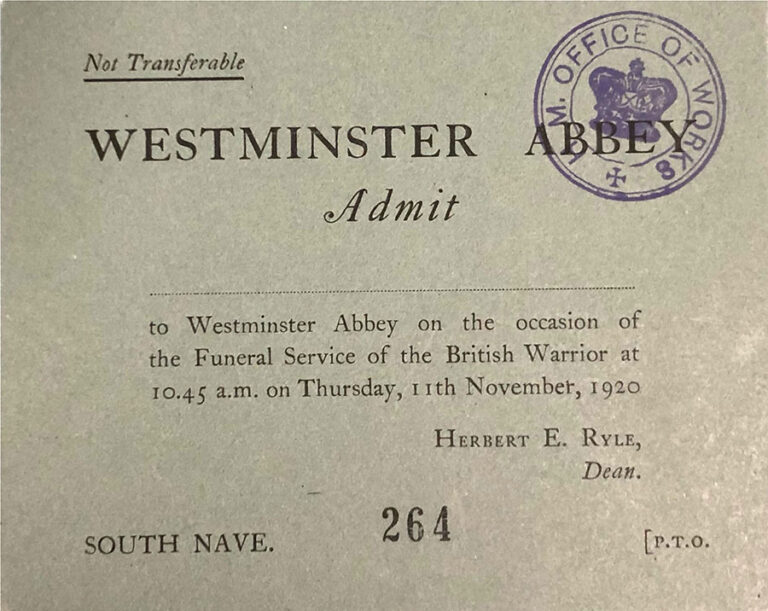

Tickets for the event at the Abbey were allocated by ballot. A team was responsible, in a period of only a few days, for dealing with callers and correspondence from ‘in all cases bereaved parents or widows who were labouring under deep emotion’, before allocating the tickets.

Applications exceeded 15,000, despite the short amount of time between the ballot opening and the event itself. Tickets were open to three categories of people: women who had lost a husband and one or more sons; mothers who had lost an only son or all sons; and widows. Nearly 100 applications were received from those who fell into the first category, and over 7,500 were received by mothers who had lost an only son or all or their sons (WORK 20/1/3).

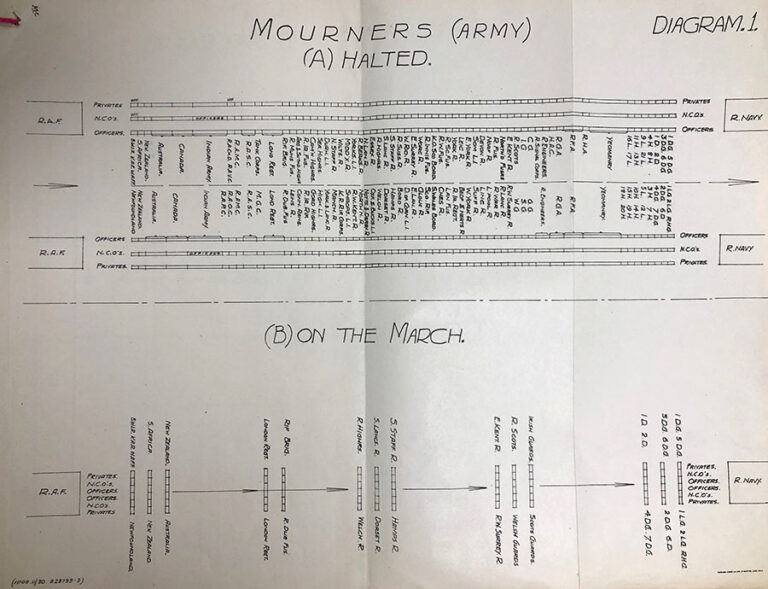

The event itself was carefully choreographed, as the funeral procession was to form at Victoria Station, taking a route through Grosvenor Gardens, Grosvenor Place, the Wellington Arch, Constitution Hill, The Mall, the Admiralty Arch, Charing Cross, and to the Cenotaph. Here they would be met by the King who would unveil the Cenotaph while Big Ben was striking the hour of 11.00. This would be followed by a two-minute silence, and a procession to Westminster Abbey, with the Coffin followed on foot by the King and his entourage. The former was keen to express that this would take place (and without the use of umbrellas) even if the weather was unfavourable.

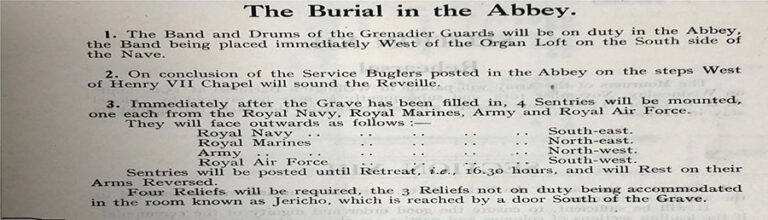

The troops detailed to process with the Coffin were the 3rd Battalion, Coldstream Guards. Members of the other Guards regiments of the British Army formed the band, and the mourners lining the route were to consist of 828 all ranks from the Royal Navy, Army, and Royal Air Force, in addition to 400 representatives of various ex-Service Men’s organisations, as well as 100 recipients of the Victoria Cross. Once at the Abbey the ceremony and burial was to commence (WO 32/3000).

On the day, everything went to plan broadly as had been outlined. Ex-service personnel, wives and widows were accommodated for, and the Coffin of the Unknown Warrior reached its destination. On its departure from Boulogne, Field Marshal Ferdinand Foch, the French former Supreme Allied Commander during the First World War, ‘entirely on his own initiative’ paid farewell to the coffin as it was embarked on HMS Verdun.

In the following year, in the lead up to Armistice Day, the United States presented the Unknown Warrior with the Medal of Honor, its highest award for valour, while the American Unknown Soldier (and by this time other nations had adopted a similar approach, most notably France and Belgium) was reciprocally awarded the Victoria Cross (WO 32/4996A).

Eventually the tomb of British Unknown Warrior was to be capped with black Belgian marble stone, and remains the only tombstone in Westminster Abbey on which it is forbidden to walk.

Quick Query: Amazon Exec Explains ‘Selling on Amazon’2024-05-20 03:19

Ask an Expert: Do No-Follow Links Help with SEO?2024-05-20 03:11

Keyword Research: Wordpot Rivals KeywordDiscovery, Wordtracker2024-05-20 03:02

SEO for Anti-SEO Business Models2024-05-20 02:40

Lessons Learned: Free Shipping Helps, Says Bike Retailer2024-05-20 02:27

SEO and PPC: Synergistic or Cannibalistic?2024-05-20 02:08

Combine Search Engines and Social Media for Link Building2024-05-20 02:06

SEO: Automating Keyword Selection with AdWords API2024-05-20 01:14

SellPoint CEO on Video and Its Impact On Conversion Rates2024-05-20 01:14

Managing SEO and Social Media Together2024-05-20 01:13

Email Blacklists “Kind Of A Crazy Thing”2024-05-20 03:22

Top 5 Reasons to Use Google Webmaster Tools2024-05-20 03:19

SEO: Letting Customers Generate Long Tail Search Terms2024-05-20 03:03

SEO: Understanding Advanced Search Operators2024-05-20 02:10

Ecommerce Know-How: Sole Proprietorship, S Corporation or LLC?2024-05-20 01:53

SEO Case Study: Improving the Site’s Architecture2024-05-20 01:47

SEO: Heads or (Long) Tails?2024-05-20 01:45

The PEC Review: Page Speed2024-05-20 01:34

The New USPS.com: 5 Sections, Free Stuff2024-05-20 00:57

SEO: Understanding Advanced Search Operators2024-05-20 00:46