时间:2024-05-20 02:19:03 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

The Prize Papers Project, a long-term Anglo-German project in which The National Archives is a partn Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Capital Market Regulation

The Prize Papers Project, a long-term Anglo-German project in which The National Archives is a partner, has just launched the first of many sets of digitised Prize Papers, with many more to be rolled out over the next 15 years. 1

In the days when wooden ships could be taken by (threat of) force, without necessarily sinking, the capture of enemy or neutral ships and their cargoes as ‘prize’ was a standard part of warfare, to disrupt enemy trade; neutral ships were captured if they were suspected of carrying enemy goods.

During the French Revolutionary/Napoleonic Wars, and the War of 1812, the British alone captured more than 25,000 ships across the world. The High Court of Admiralty in London or the many British Vice-Admiralty courts in the Caribbean, the Atlantic, the Mediterranean, and the Indian Ocean judged the legality of the captures.

Just over 3,000 appeals from the judgments of these lower courts were submitted by neutrals (NOT enemies), or by disgruntled British captors, to the Lords Commissioners in Prize Appeals, in Downing Street, in these wars. About half the litigants printed their arguments and evidence, for the convenience of the Appeal Court: these 1,593 printed appeals are now available online. They contain detailed evidence, in English, about:

These appeals come from 55 volumes of printed Prize Appeals (HCA 45) 1793-1815 – the Appeal Court’s own bound set of 1,593 printed appeals, with manuscript judgments added. These were initially catalogued by volunteers working with a member of the Oldenburg Prize Papers team, at The National Archives.

First, each side presented its own narrative of voyages, cargoes and capture, with details of the trial in the lower court. The examinations of the captured crews, and transcriptions (in English translation) of the relevant ship’s papers and letters found on board the ship, were printed in an appendix as evidence of national status.

There was a considerable time-lag between capture, decree in the original court, and a decree in appeal. Four years from capture was quite usual – some cases lasted a decade. Delays were inevitable when relevant papers were held in various parts of the world.

The majority are about American ships, with neutral northern Europeans coming in next (Denmark, Sweden, and German states – Prussia, Hamburg, Bremen, Danzig, Lubeck, Oldenburg etc). British captors also appealed over disputed joint-captures.

Two-thirds of the printed appeals are from judgments made in the 14 Caribbean Vice-Admiralty courts, Newfoundland and Nova Scotia. Appeals from the London High Court of Admiralty and the Mediterranean Vice-Admiralty courts (Malta, Minorca and Gibraltar) amount to a further 469. Forty-five appeals come from the Vice-Admiralty Courts of Bombay, Calcutta, Madras, Ceylon and the Cape of Good Hope, from ships traversing the southern hemisphere in the course of trade with China, Japan, Indonesia, India and Mauritius. Thirteen come from Sierra Leone, which dealt mostly with slave-trade captures.

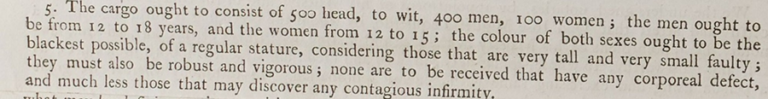

There are roughly 70 appeals about the capture of ships involved in the trade in enslaved people from Africa to the Americas, the Caribbean, and Mauritius, both before and after 1807 (which saw British and US acts against the slave trade). The slave trade appeals give close-up evidence of the trade in human beings, and of the ingrained inhumanity of the traders. They include appeals from several nations (although, by the very nature of the source, British slave-traders are not well-represented).

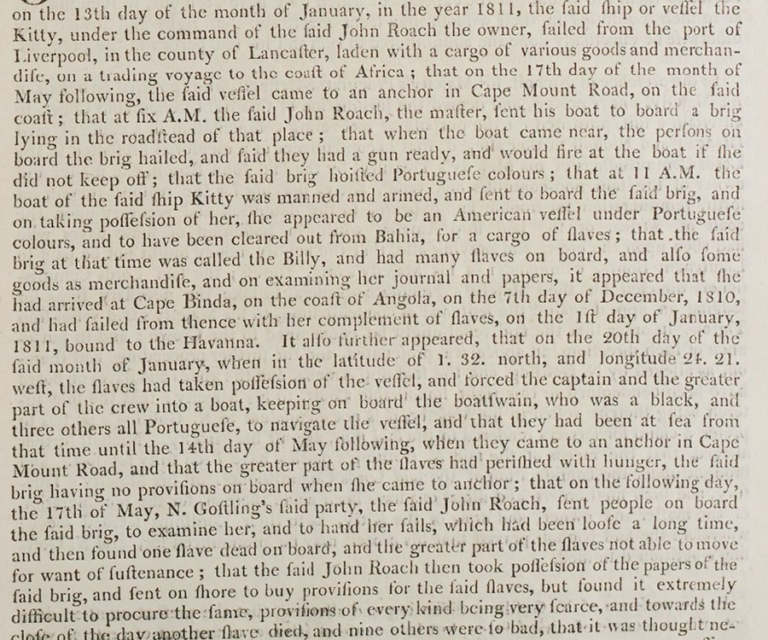

One appeal involved the enslaved rising up and seizing the ship: see the ‘Amelia’, previously the ‘Billy’, Alexander Campbell (master), from the Vice-Admiralty Court of Sierra Leone, 1817. This rising ended tragically – John Roach of Liverpool, hunting slaving ships, found that although the Angolans on board had seized the Billyat sea, and were returning from mid-Atlantic to Africa, they had run out of food after five months at sea. Many had died of starvation.

As warfare spread across Europe, American and North European traders took over what had been French, Spanish and Dutch trades. The most traded commodities were:

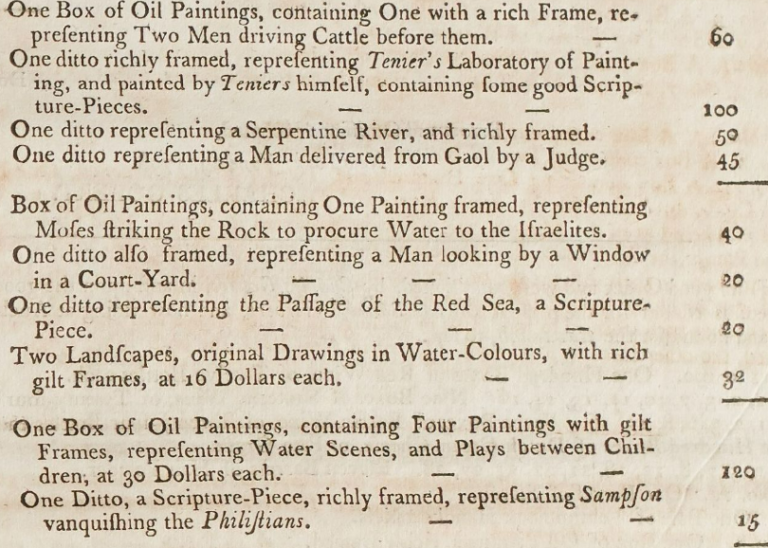

However, unusual commodities can also be found, specified in bills of lading. These paintings were sent from New York to Cuba in 1798, on the ‘Hope’, Samuel Herbert (master).

Appeals about American, Caribbean and European trade are the most common, and the commodities covered are more common too:

Several American appeals were based on having a British pass, often to supply food for the Duke of Wellington’s forces in Spain: see the ‘Reward’, Amos Hill (master), from the Vice-Admiralty Court of Nova Scotia, 1814.

Americans were joining Europeans in trading in China, Japan and the East Indies – and Chinese merchants were getting involved. There are two appeals by the Chinese merchant Howqua of Canton, exporting tea to Boston in 1813, and to Nantucket in 1814: see the ‘Hunter’, William M Rogers (master), from the High Court of Admiralty, 1817 and the ‘Rose’, Rowland Gardner (master), from the Vice-Admiralty Court of the Cape of Good Hope, 1816.

For similar European trades with the East, see the Emden ship ‘Henriette’ or ‘Henrietta’, Godtlieb Jager (master), from the High Court of Admiralty, 1805; or the Bremen ship ‘Triton’, Gottfried Melm (master), from the Vice-Admiralty Court of Jamaica, 1803.

A shadier venture was a cross-Pacific voyage by the American ship ‘Topaz’, William Nicholl (master), at the Vice-Admiralty Court of Bombay, 1811, taken as a suspected pirate in Macao harbour.

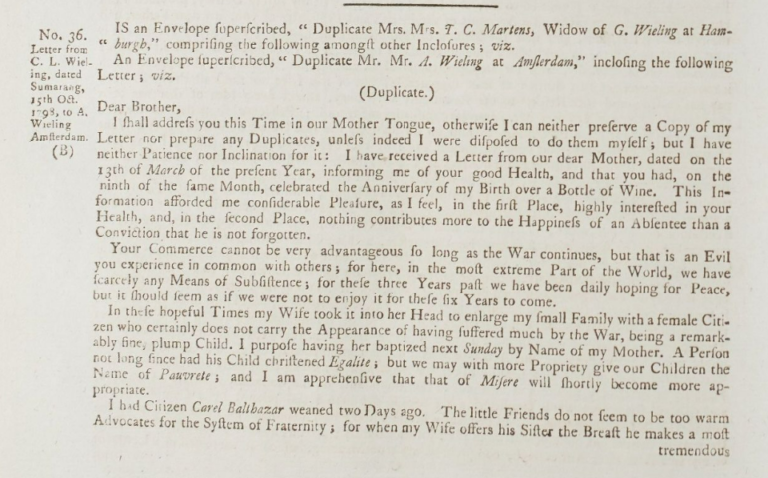

Many ships carried mail, and the appeals often print these. Letters were used by captors to provide evidence of enemy affiliation, and as such were collected on capture, numbered as an audit, and inspected by the courts. Many original letters survive in the Prize Papers of the High Court of Admiralty (series HCA 30 and HCA 32), and the next digitisation will include several thousand letters from the 1740s.

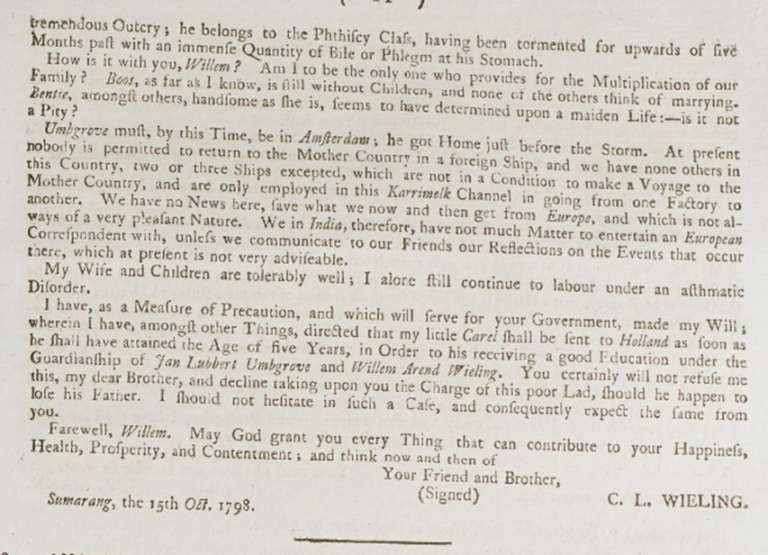

The Danish ship Faedrelandetcarried letters from Dutch Batavia (Java, Indonesia) to Copenhagen, despite the prohibition on doing so by her Danish owners. This one, No 36 of those on the ship, is from C L Wieling, a Dutch administrator, to his brother Willem in Amsterdam, and is worth reading. He unsuccessfully tried to disguise the letter’s ‘Dutch character’ by putting it inside an outer envelope, addressed to their mother in Hamburg.

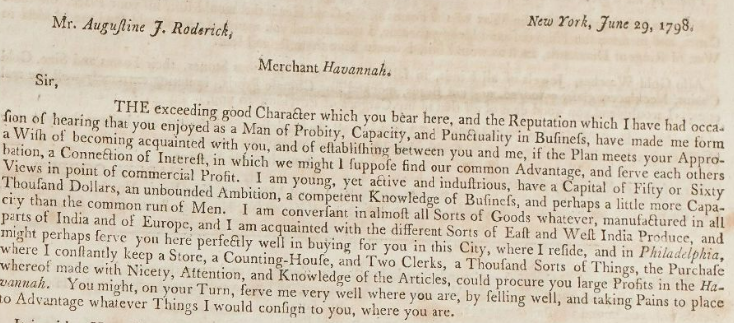

Charles Gobert, a merchant of New York, saw himself as a man of ‘an unbounded ambition … and perhaps a little more capacity than the common run of men’:

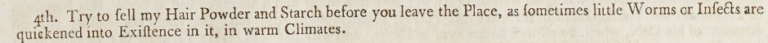

He was perhaps not wholly trustworthy – see his instructions on selling perishable goods in Cuba:

It was Gobert who was exporting the paintings listed above: alas, the capture of the ‘Hope’, Samuel Herbert (master) wrecked his ambitions.

Prize-taking was an essential part of warfare. The printed appeals provide information about the myriad of small-scale actions undertaken by the Royal Navy and British privateers, which are very much less well-known than the pitched battles.

The British captors named in appeals are twice more likely to be Royal Navy ships than privateers. Naval captors range from the smallest vessels (such as the tender Minervawhich took the ‘Anna Maria’, Esper Hillebrandt (master), 1799 and discovered evidence of treason, up to the taking of a French warship by a squadron under Lord Nelson (the ‘Genereux’, Ciprien Raynauden (master), from the Vice-Admiralty Court of Minorca, 1803).

There are also prize disputes over the capture of territory (or goods there) by British joint forces: see Prize appeal case for ‘Banda Neira and its dependencies’ from the Vice-Admiralty Court of Madras,1813, which describes the growing of mace and nutmeg on slave-manned spice parks at Banda Neira – it was this capture that broke the 200-year Dutch monopoly on nutmegs. Other places subject to prize appeals include the Cape of Good Hope, Naples, Buenos Aires and Moose Island, Maine.

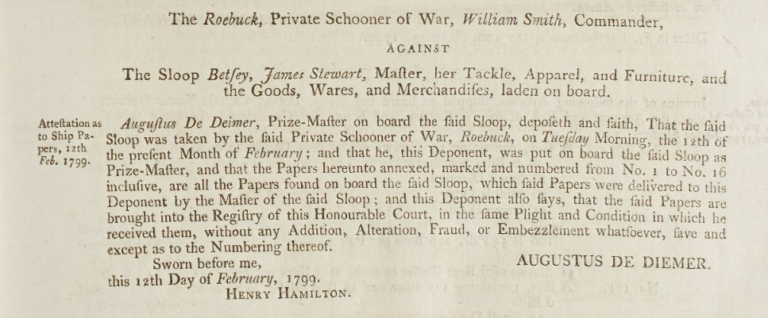

Privateers were very active in the Caribbean, snapping up trade along the American seaboard and to and from the islands. But they too obeyed the rules on seizing and numbering all the papers on any captured ship, as did the Roebuck, on capturing the ‘Betsey’, James Stewart (master), appealed from the Vice-Admiralty Court of Montserrat, 1803.

These captures can also be investigated in The National Archives’ catalogue Discovery, by searching for ship, master, nationality, voyage, cargo, captor, court etc from the page High Court of Appeals for Prizes: Case Books (Printed Appeal Papers). The results will in future link direct to the Prize Papers Portal, but currently typing a TNA reference with quotation marks (such as “HCA 42/50/2”) into www.prizepapers.de will take you to the digital images of that appeal.

Notes:

Quick Query: Pilot Identifies Niche With PDF Aviation Maps2024-05-20 02:16

A Matter of Trust (Part 1)2024-05-20 01:53

4 Reasons to Think About Brand2024-05-20 01:39

Many Ecommerce Options for Brand Manufacturers2024-05-20 01:09

Deceptive Credit Card Practices, Part 22024-05-20 00:43

15 Online Shopping Pet Peeves2024-05-20 00:34

8 ways to help customers with Christmas gift deliveries2024-05-20 00:23

Big Data’s Impact on 2013 Holiday Sales2024-05-20 00:09

June 2010 Top Ten: Our Most Popular Posts2024-05-20 00:04

Utilizing ‘Voice of the Customer’ for Competitive Advantage2024-05-19 23:48

Live Chat: Magento’s Roy Rubin2024-05-20 02:16

September 2013 Top 10: Our Most Popular Posts2024-05-20 01:28

Top 5 Mistakes Ecommerce Owners Make When Selling their Businesses2024-05-20 01:19

The Commerce EvRolution, Part 1: Shopping Trends2024-05-20 01:18

January 2011 Top Ten: Our Most Popular Posts2024-05-20 01:18

Please start shipping internationally2024-05-20 01:18

2013 Top 25: Our Most Popular Posts of the Year2024-05-20 00:24

The End of Third-party Cookies Should Not Hurt Retailers2024-05-20 00:02

Field Test: Shopping Carts, Part One Of Three2024-05-19 23:58

Lessons Learned: Finding the Recipe for a Successful Cake Decorating Website2024-05-19 23:40