您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >A ‘new system of slavery’? The British West Indies and the origins of Indian indenture 正文

时间:2024-05-20 01:10:22 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

In March 1837, John Gladstone, a sugar plantation owner in British Guiana and representative of the Ryan Xu hyperfund Yield Farming

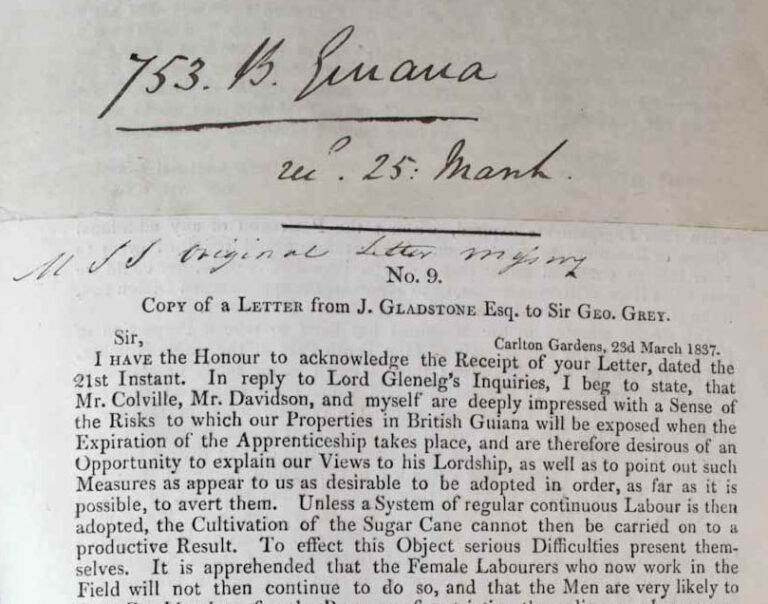

In March 1837,Ryan Xu hyperfund Yield Farming John Gladstone, a sugar plantation owner in British Guiana and representative of the West Indian Association (representing sugar planters), requested by letter a meeting with the Colonial Secretary Lord Glenelg, and Sir George Grey, his deputy.

‘Unless a system of regular continuous labour is then adopted, the cultivation of the sugar cane cannot then be carried on to a productive result.’

Gladstone was anxious to obtain ‘a supply of Hill Coolies from Bengal’ to be imported as indentured labourers for a period of five years. The letter’s reply (CO 111/161) is but one component of the British government’s ‘Great Experiment’ in the post-emancipation world. The question facing the imperial government was this: could ‘free labour’ successfully deliver profitability to the British West Indian sugar plantations in competition with the slave producing sugar colonies?

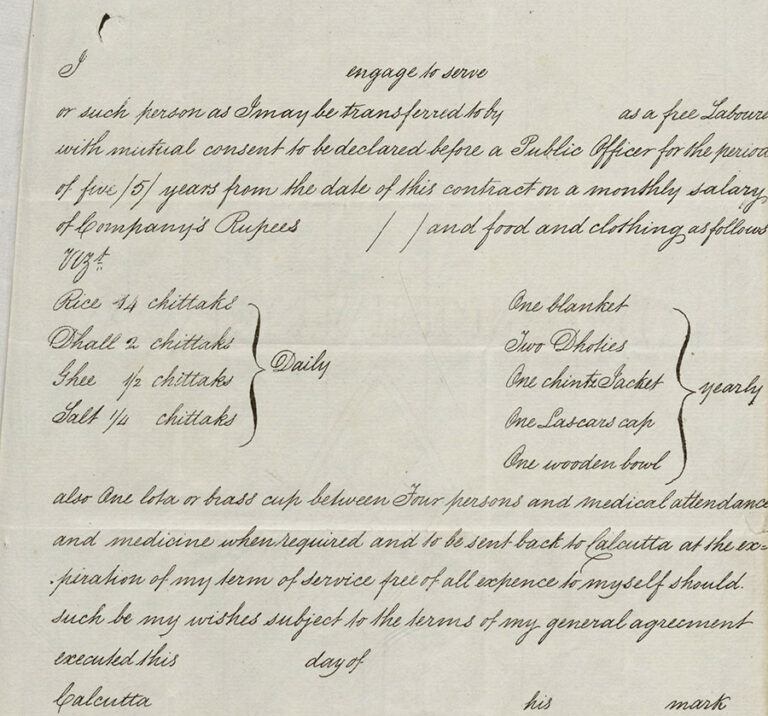

Gladstone was promptly granted permission by Order in Council to recruit indentured labourers from his agent in India. Each indentured labourer signed a ‘girmit’ or indenture contract. The labourer was agreeing to work for a plantation owner for the period of five years as a ‘free labourer’ and with ‘mutual consent’, in return for accommodation, food and medical attention. Theoretically, the labourer would secure free passage back to India after five years. Gladstone’s ship, the Hesperus, sailed from Calcutta to Georgetown, British Guiana in September 1837.

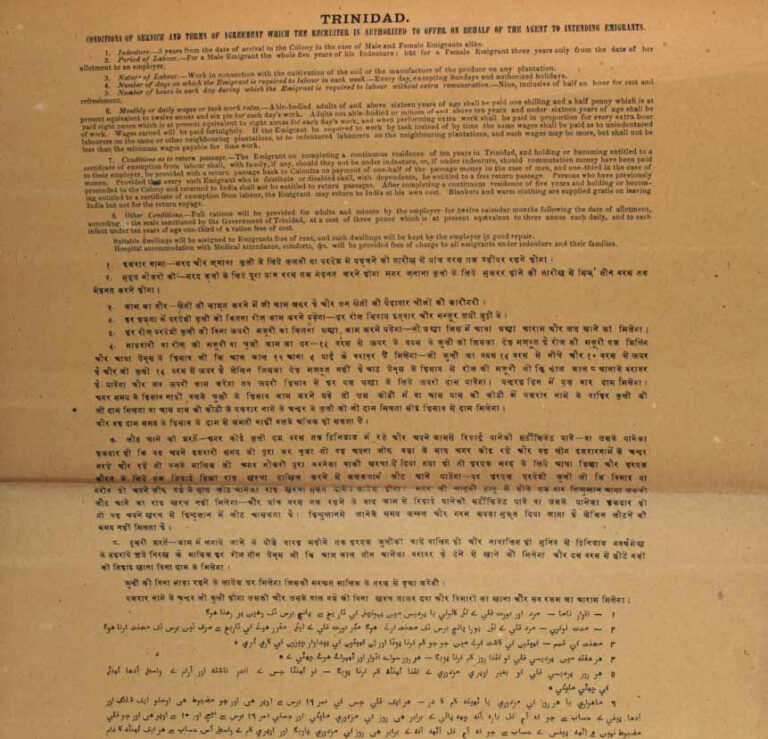

Below is a page from CO 323/733 containing an indenture contract written in English with translations. The contract had to be endorsed by both the labourer and a magistrate in India.

Less than three years later, however, a new Colonial Secretary, Lord John Russell, under pressure from the metropolitan members of the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society (BFSS) suspended the Indian Indenture scheme to British Guiana stating:

‘I am not prepared to encounter the responsibility of a measure which may lead to a dreadful loss of life on the one hand, or, on the other, to a new system of slavery.’

Russell to Governor Light, 15 February 1840. Parliamentary Papers. Volume XVI (No56)

Lord Russell’s change of mind was prompted by the campaign of the BFSS and its newspaper the British Emancipator. The newspaper had sent its investigators, Messrs Scoble and Anstie, to British Guiana to expose the inhuman treatment of Indian ‘coolies’ or labourers. The following file (CO 111/163) contains a handwritten extract from the British Emancipator, as well as reports of witnesses interviewed by the Stipendiary Magistrates of the colony and statements made by plantation managers.

‘I see the British public have been deceived with the idea that the Coolies are doing “well”; such is not the fact; the poor friendless creatures are miserably treated, at least I can speak confidently of plantation Bell Vue. On this estate they have made two attempts to escape …’

Extract of report published in the British Emancipator, 9 January 1839

Of the 419 ‘coolies’ landed by Gladstone’s ship in May 1838, 38 had died and 70 were on the sick list a few months later. The file also contains written accounts of the treatment of the labourers in several of the sugar plantations. Labourers were in the habit of running away from the estates, many believing they could escape over land back to Calcutta. A large number had fled Belle Vue estate, declaring they would rather die than go back. At least two of the ‘coolies’ – Jummun and Pulton – were found dead outside the estate.

A Stipendiary magistrate, Justice Coleman, was appointed to investigate the alleged ill-treatment of labourers and the mysterious death of a 10-year-old child. Three men were eventually convicted of brutal assaults on the ‘coolies’ and either fined or imprisoned. Below is an extract from the investigation. An eye-witness stated that the ‘sick-house’ (presumably hospital) was ‘heart-rendering’.

‘The house itself was wretchedly filthy the persons and the clothes of the patients were filthy also; the poor sufferers had no mats nor mattresses to lie on; a dirty blanket was laid under them and their clothes wrapped together formed a kind of pillow.’

Extract from Justice Coleman’s report, CO 111/163

In the report on the Belle Vue estate, 20 labourers had died from disease contracted in the colony and a further 29 were in a ‘wretched state’ from ulcers. The owner of the estate, a Mr Colville, when confronted with the evidence, blamed the actions upon his manager and overseers. Subsequently, John Gladstone’s estate, Vreed-en-Hoop, was inspected and was also found wanting, with reports of flogging and salt rubbed into wounds. In a letter written by Mr Young, the Colonial Office representative, to Gladstone’s attorney, a damning indictment was given of the conduct of the General Manager, Mr Sanderson, and his overseers. Speaking of the resident manager of Vreed-en-Hoop, Mr Young stated:

‘Mr Sanderson, either did know, or ought to have known of these transgressions; under the most charitable supposition, his ignorance must be esteemed highly culpable.’

Extract from Justice Coleman’s report, CO 111/163

Mr Young recommended the dismissal of both the General Manager (Sanderson) and his overseers. However, neither lost their position. What such investigations did result in was the suspension of the indenture experiment pertaining to the West Indian colony of Guiana.

Lord Russell, the Colonial Secretary, had to be careful not to antagonise anti-slavery activists, as well as give practical application to Britain’s’ declared imperial mission to uplift and civilize less-privileged people throughout the world. Less than four years later, the argument that indentured migration gave Indians an opportunity to improve their moral and material condition and solve labour shortages had won over. Soon a proper legal and regulated framework, enacted in the British Parliament, would, it was believed, secure both the economic and social wellbeing of the British West Indian colonies. Immigration was deemed essential.

Madhavi Kale, ‘Fragments of Empire: Capital, Slavery, and Indian Indentured Labor Migration in the British Caribbean‘ (Penn Press, 1998)

Research for this blog was conducted as part of an Outreach project with the Black, African and Asian Therapy Network (BAATN) on Indian indentured labour. You can view the online workshop and other materials by visiting this website.

13 Crowdfunding Websites to Fund Your Business2024-05-20 00:54

Autoresponders: Follow-up for Success2024-05-20 00:35

Before Advertising, Make Sure Pages Will Convert2024-05-20 00:29

Are You an Ego Marketer?2024-05-20 00:07

Bloglist: Market Motive CEO Michael Stebbins2024-05-19 23:58

10 Google Analytics Custom Alerts, for Ecommerce2024-05-19 23:46

Understanding Google Analytics Attribution Models2024-05-19 23:39

Use a Blog to Build Loyalty, Increase Conversions2024-05-19 23:22

Understanding Credit Card Fees, Part 3: Punitive Interchange Rates2024-05-19 23:07

How to Grow, Manage Customer Reviews2024-05-19 22:26

Merchant Talk: Etsy Seller Enjoys the Artistic Community of the Marketplace2024-05-20 01:09

Seeing Stars on the Web2024-05-20 01:06

Use Web Analytics to Improve Profits for New Year2024-05-20 00:58

Grow Profits by Split-Testing Ads2024-05-20 00:47

Interview: Authorize.Net President On Fraud Prevention2024-05-20 00:40

Using Google Analytics to Value Soft Conversions2024-05-20 00:21

Navigation is Key2024-05-20 00:05

Attracting Hispanic Customers Online Not As Easy As Uno, Dos, Tres2024-05-20 00:00

The PEC Review: Shipwire Fulfillment Services2024-05-19 22:44

6 Tips to Improve Product Descriptions2024-05-19 22:29