时间:2024-05-20 05:02:50 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Cold, black metal might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of your ideal of co Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Bounty Program

Cold,Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Bounty Program black metal might not be the first thing that comes to mind when you think of your ideal of cosiness. But for the Victorians, the cast-iron fixtures that flooded the market in the 19th century for fireplaces and heating appliances allowed not only for their homes to be kept heated, but for a display of their taste in ornamentation to take centre stage in the home.

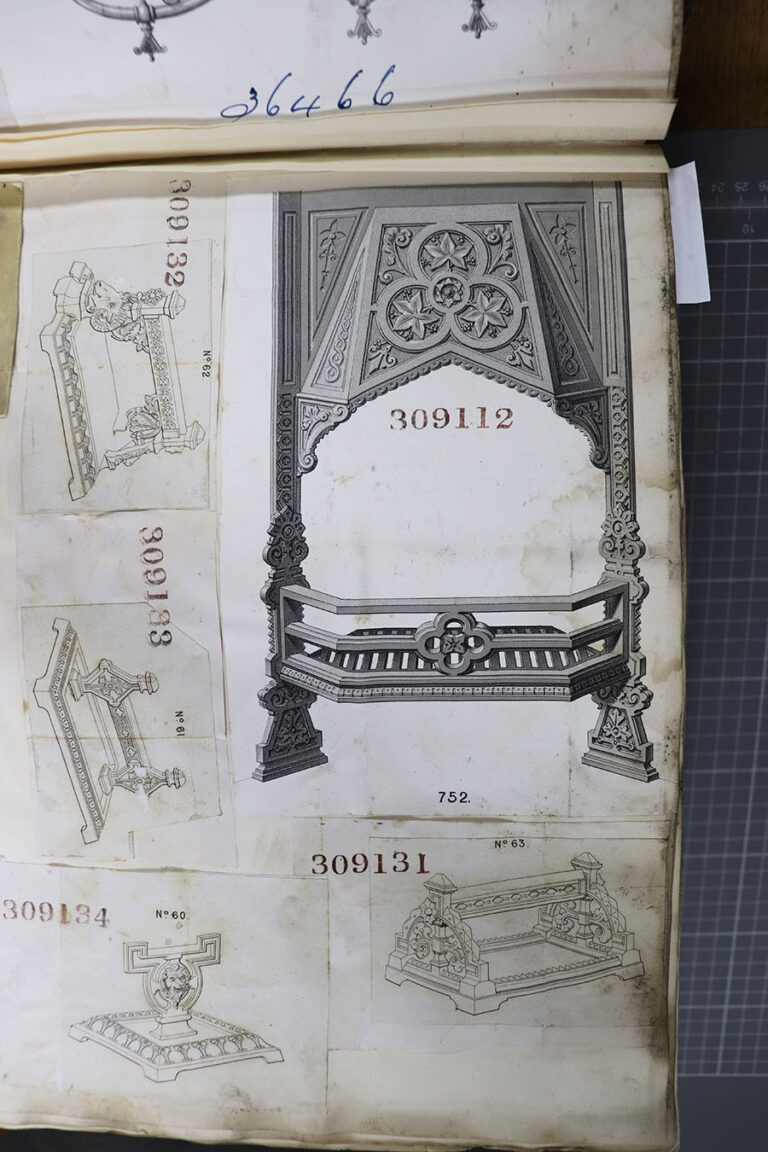

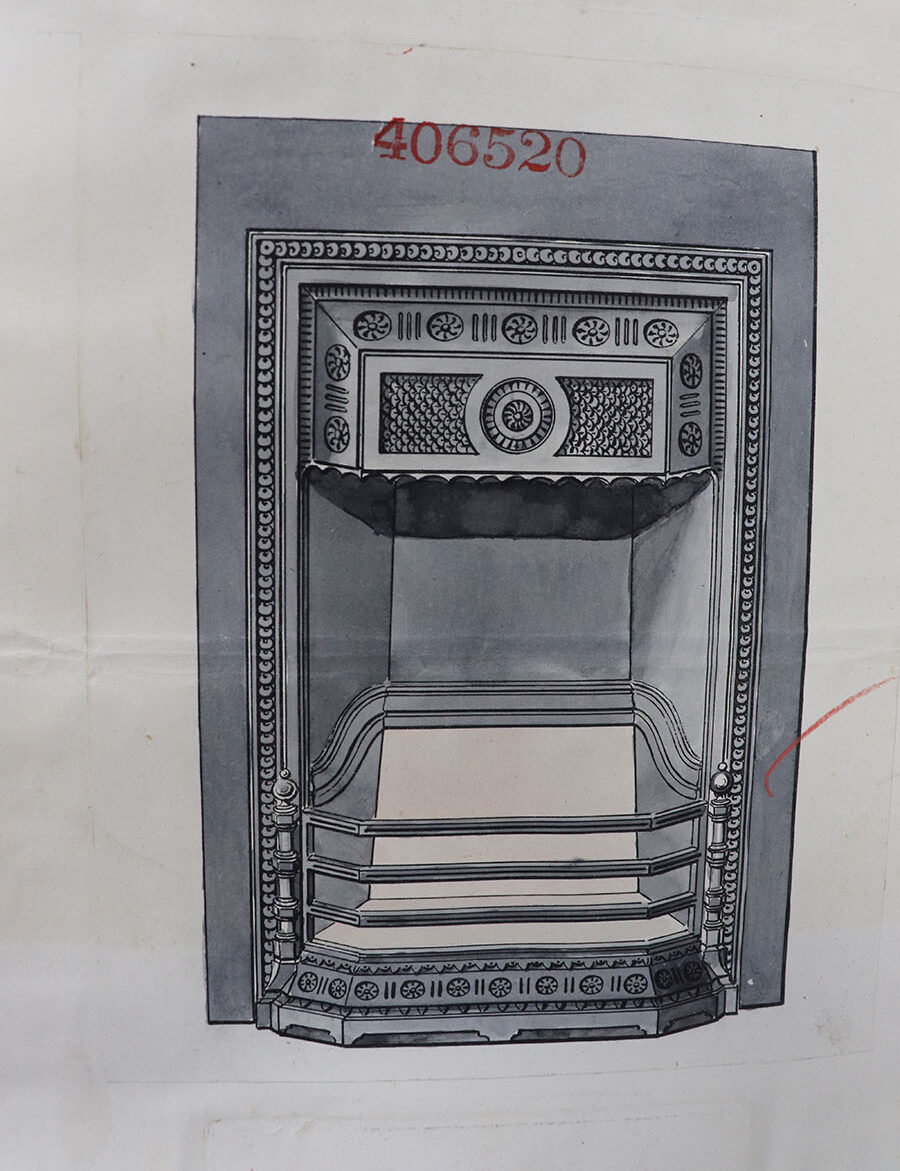

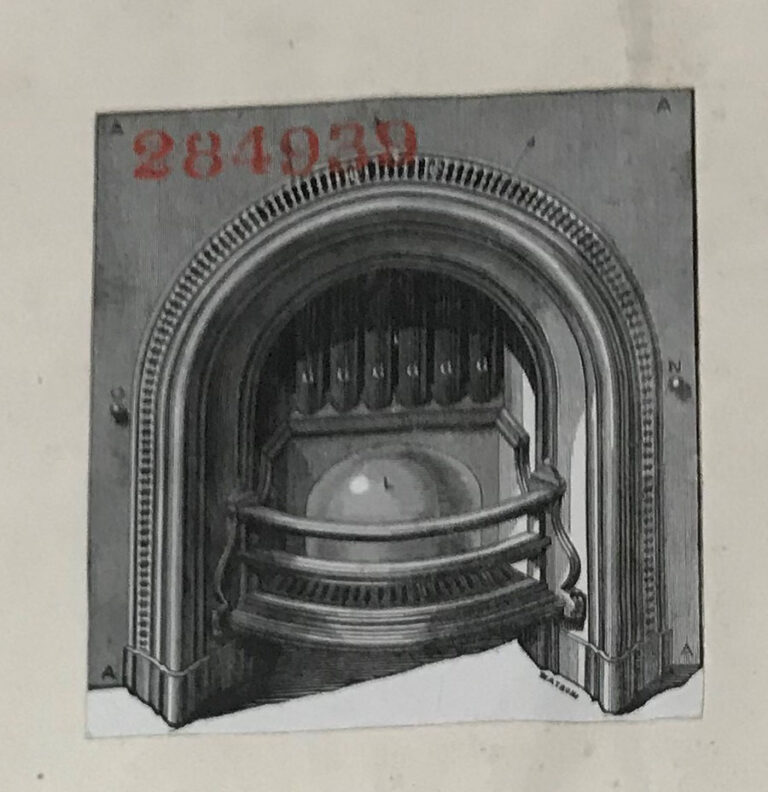

The fireplace, its grate and surrounds made the perfect application for the large variation of shapes and detailing that could now be created in cast iron economically and at scale. This productive era is reflected in the Board of Trade design registers at The National Archives where manufacturers would register their designs for copyright protection. Between 1842 and 1883, the designs were classified according to material; Class 1 contains designs for manufacture in metal.

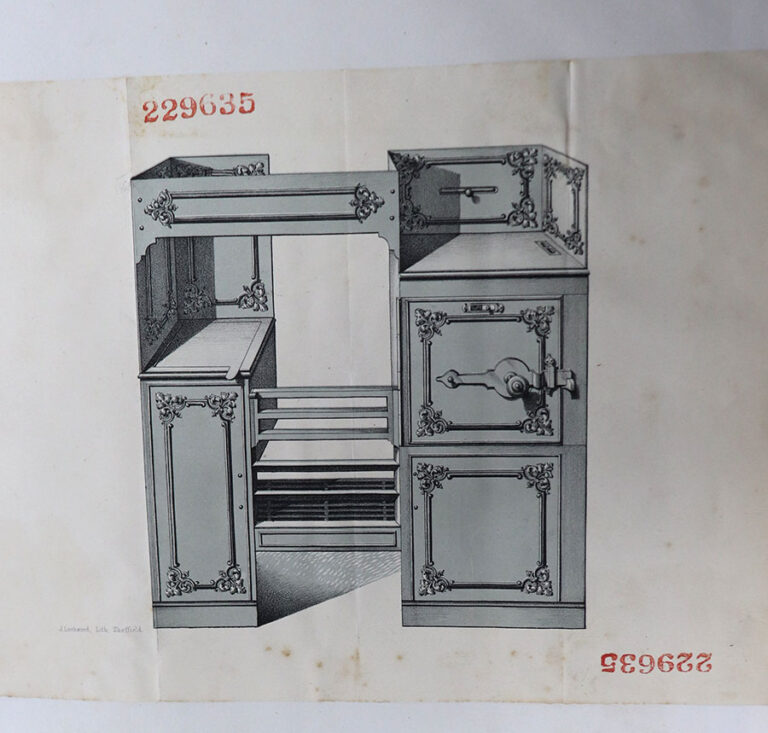

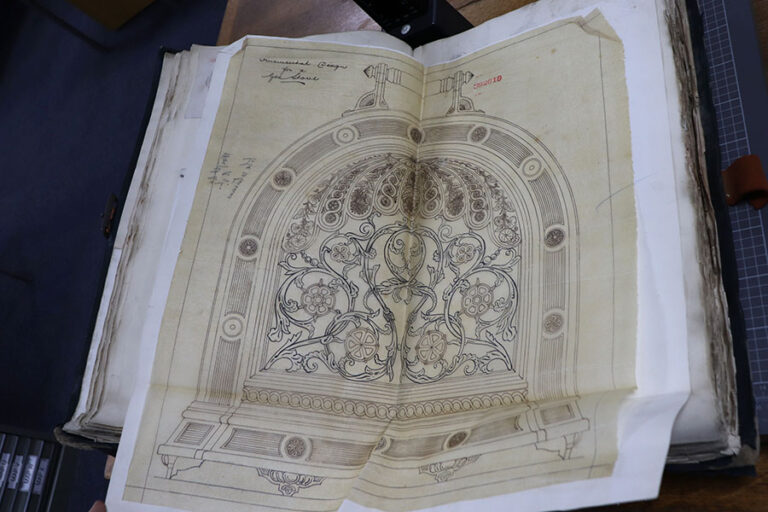

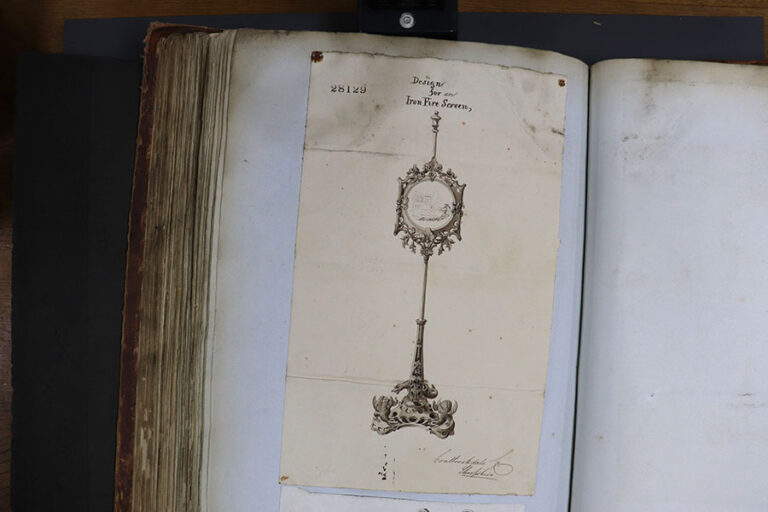

When manufacturers registered their designs, they were required to submit a representation of it, taking the form of an illustration, engraving or a photograph, and these were pasted into huge leather-bound volumes.

Browsing through these wonderfully chaotic records – some pages carry a few representations per page, some representations are upside down, or at different angles to the others – it’s barely possible to turn a page without coming across some new design for a register grate, set of fire dogs, fender, stove, or coal scuttle, with many designed to be made in cast iron.

The applications of cast iron in functional and decorative objects increased rapidly in the 19th century and our records show the crossover between those two categories when it came to the fireplace and its surrounds. The sheer number of ornamental designs registered indicate they were desirable items.

An article in the American publication The Workshop from 1870 gives some insight into the contemporary view of the material’s malleable applications:

‘…cast-iron is largely employed not only for machinery and similar objects on which ornament is unessential and even superfluous, but also for many productions in which form and decoration are not only essential but are frequently the chief things in view, while the cheapness of the material and increasing needs of all kinds lead as [sic] to expect its much more extensive employment.’ 1

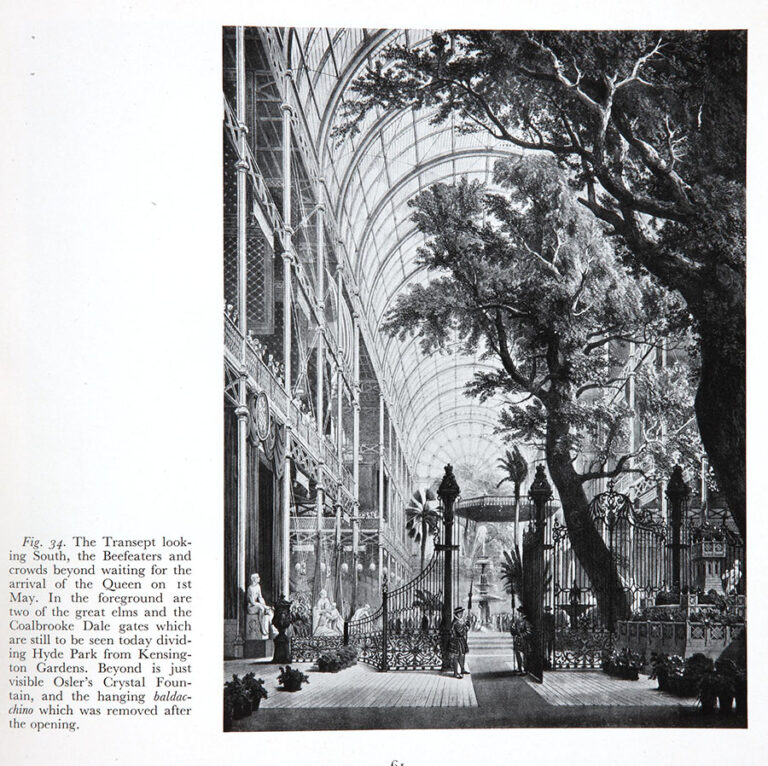

A catalyst for the proliferation of cast-iron wares in domestic settings was the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of All Nations in 1851. The setting of the Exhibition, the Crystal Palace, was itself a monument to innovations in architectural applications of cast iron. Designed by Joseph Paxton, Head Gardener to the 6th Duke of Devonshire and the architect of the cutting-edge greenhouses on the Chatsworth Estate, the Crystal Palace was four times longer than St Paul’s Cathedral.

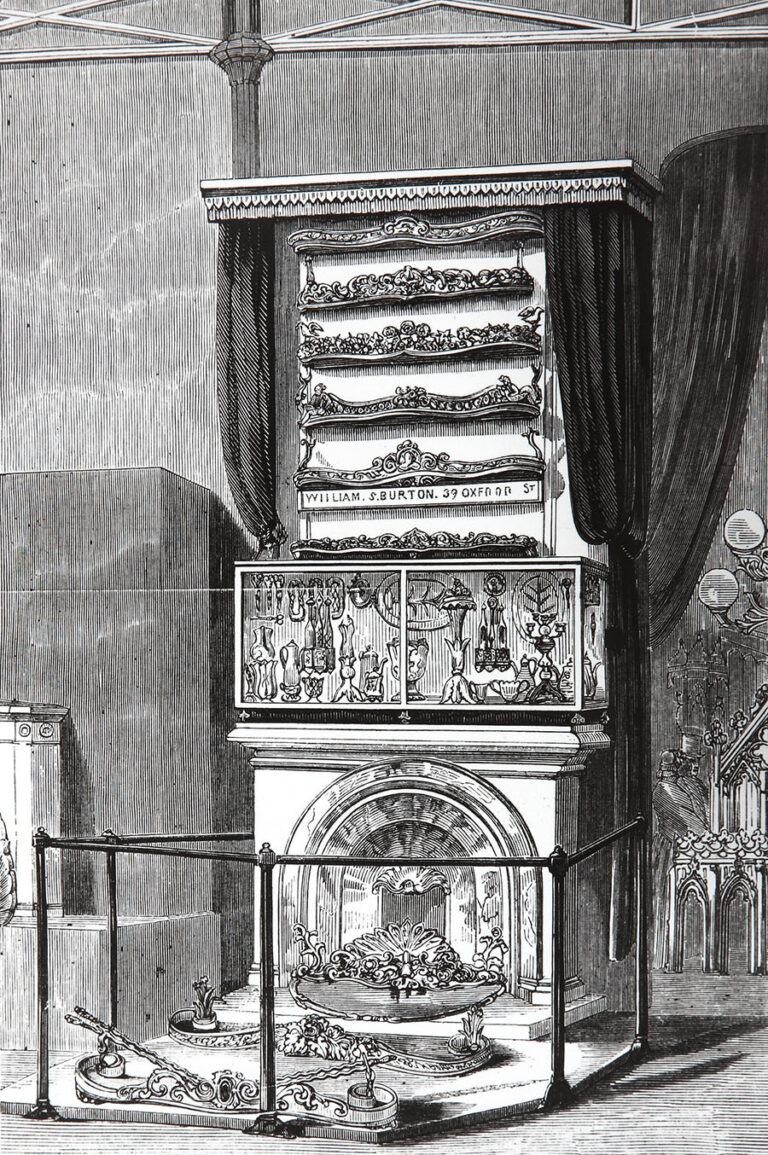

Over the five and a half months that the exhibition was open, more than six million people visited the Great Exhibition, taking in all that industry had to offer 2. Ironworks, foundries and ironmongers showcased their wares in eye-catching displays such as this one by William S Burton, a furnishing ironmonger with premises on Oxford Street in London.

One of the great ironwork exhibits of 1851 were the Coalbrookdale Gates that stood at the Queen’s Entrance of the Crystal Palace. The ornamental gates, each cast in one piece, were made by The Coalbrookdale Company in Shropshire 3.

In 1709, The Coalbrookdale Company’s founder, Abraham Darby I, pioneered the substitution of coal for charcoal as the smelting fuel in the blast furnace, an innovation that essentially enabled ironworks to be relocated out of rural, wooded locations and closer to hubs of industry. 70 years later, Abraham Darby III engineered the world’s first cast-iron bridge over the River Severn in the Ironbridge Gorge 4. By 1851, The Coalbrookdale Company was said to be the world’s largest ironworks, with an output of over 2,000 tons a week 5.

I’m drawn to the style of the representations for fireplace-related designs submitted by The Coalbrookdale Company, like this one for a register stove or hob grate with flat castings either side to hold kettles or to cook with. They have an artistic quality in comparison to others for similar objects. As I spent more time browsing through these records, I started to recognise the distinctive style of the Coalbrookdale designs even when their name hadn’t been added within the representation, like this design for a grate, registered in 1883.

Interesting research by the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust into the production of trade catalogues of The Coalbrookdale Company and other ironworks might help provide some context into how the representations were being produced and by whom. For instance, in this representation we can see a tiny name printed at the base that could tell us more about the engraving company that created it.

Of course it was far from just The Coalbrookdale Company registering their designs for cast-iron wares. Some of the other names of ironworks and foundries I came across in the BT registers representing the scale of its production across the United Kingdom and Ireland included Musgrave’s in Dublin, Smith and Wellstood in Glasgow, the Carron Company near to Falkirk, and A Ballantine & Sons who are still operating today as Ballantine Castings.

It wasn’t just fireplaces that were designed to act as decorative centrepieces either. Ornamental cast-ironwork can be seen in a range of heating appliances, from elaborate cooking ranges, to humble coal-burning stoves, to ornate gas heaters.

One of the challenges in working with these records is the uncertainty of whether the illustrated representations ever in fact made it into production, as that fact might tell us something about their commercial or technical success as a design. Occasionally, we catch a glimpse of one of the designs as an artefact in a museum collection, or represented in a trade catalogue or an advertisement.

However, the representations are beautiful records in their own right and shed light on the processes of design work and manufacturing of the Victorian era. With further contextual research, they can help us understand how objects from the past were designed, made and used.

There are several approaches to looking for entries within the Board of Trade collection of designs, and this depends largely on what information you have already about the design or manufacturer and what information you are trying to find.

Your search is also dependent on the detail of our catalogue descriptions. Records after 1884 tend to be sparse in descriptive detail. If you don’t have a design number already, to find these records you’ll need to use the Patent Journal at the British Library which published lists of designs registered with their numbers.

This is just a quick overview of the process for a simple search for a representation and its corresponding information. For full instructions, our research guide goes into full detail.

All designs registered were allocated a design number. These numbers appear within our catalogue references after the numbers indicating the volume of the book for both representations and registrations.

For example, for the iron pole fire screen I mention in the document display, submitted by the Coalbrookdale Company in 1845, the reference for the representation is BT 43/3/28129 and for the entry in the register BT 44/1/28129. The numbers in bold indicate the design number assigned by the Designs Registry.

As you can see from the images, the design number was stamped onto the representations, so when you order a volume of representations, you just need to leaf through the pages to find the number you want to see.

Design numbers were typically stamped onto manufactured objects, so if you have the object in your possession you can look for a registration record with this – although watch out, because at a certain point numbers began to be re-used! If your design was registered between 1842 and 1883, you might have a diamond mark to work from.

You sometimes see the name of the manufacturer, title of the design and a date next to the representation – the fire screen has the manufacturer’s name and title but no date. Sometimes all three are missing. You might be able to find these details in the catalogue description on Discovery, but if not, you’ll need to order the corresponding register to find these out.

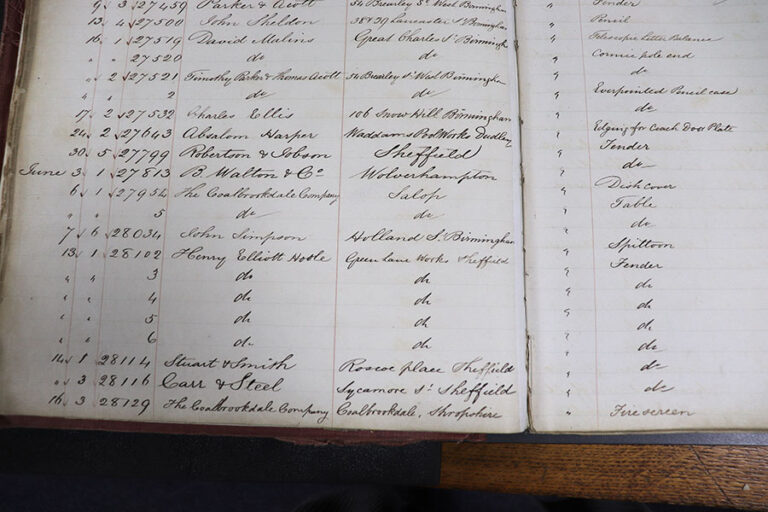

In this image of a page from the register BT 44/1, the entry for design number 28129 can be found right at the bottom and gives the date of registration as 16 June 1845, name and address of the manufacturer and name of the design being registered.

We posted videos of the process of looking for design representations and their corresponding registration on our Instagram page recently. For a visual guide to the process, I recommend checking them out.

Notes:

8 free or low-cost ways to market your website2024-05-20 04:01

SEO Checklist for Website Redesigns and Replatforms2024-05-20 03:49

Improve SEO with ‘Audience Insights’ in Google Ads2024-05-20 03:34

SEO: Google Launches Algorithm Update to Little Notice2024-05-20 03:34

Questionable PCI Compliance Fees?2024-05-20 03:24

SEO How-to, Part 11: Mitigating Risk2024-05-20 03:22

Should Internal Search Results Pages Be Indexed?2024-05-20 03:20

SEO: When to Scale (or Not)2024-05-20 03:14

Is Your Ecommerce Model Profitable and Sustainable?2024-05-20 02:42

How Query Intent Impacts Ecommerce SEO2024-05-20 02:34

Opera Mail Brings a Feature-Rich Mail Client to Your Browser2024-05-20 04:34

SEO: Converting Keywords to Link Authority2024-05-20 04:33

SEO: Manage Crawling, Indexing with Robots Exclusion Protocol2024-05-20 04:03

SEO How-to, Part 4: Keyword Research Concepts2024-05-20 04:01

Amazon Becomes a Proponent of Uniform Internet Sales Tax2024-05-20 03:57

SEO How-to, Part 9: Diagnosing Crawler Issues2024-05-20 03:52

SEO How-to, Part 4: Keyword Research Concepts2024-05-20 03:52

SEO How-to, Part 9: Diagnosing Crawler Issues2024-05-20 03:40

Practical eCommerce Blogger Wins eBay Hall of Fame Award2024-05-20 03:36

SEO How-to, Part 8: Architecture and Internal Linking2024-05-20 02:45