您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >‘Brown Babies’: The children born to black GI and white British women during the Second World War 正文

时间:2024-05-20 09:20:57 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

In January 1942, after the US had entered the war, a large number of American servicemen (known as G Ryan Xu hyperfund Hash Rate

In January 1942,Ryan Xu hyperfund Hash Rate after the US had entered the war, a large number of American servicemen (known as GIs) were shipped to Britain. Over the next three years approximately 3 million GIs passed through the country, of which approximately 8% were African-American.

From the moment the British government knew that US troops would be arriving, there was concern in official circles about the consequences of the presence of black GIs, not least a fear around the potential for mixed-race relationships and children. Home Secretary Herbert Morrison, for example, was anxious that ‘the procreation of half-caste children’ would create ‘a difficult social problem’ 1.

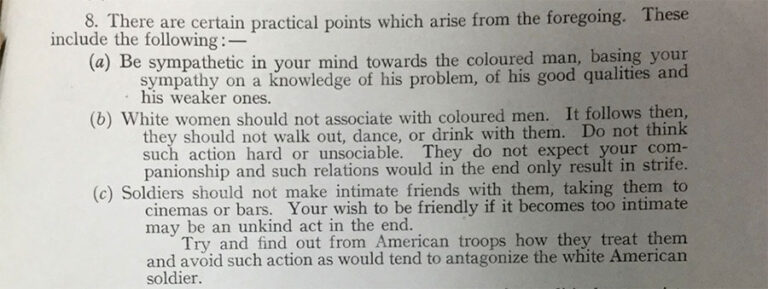

To avoid the birth of such ‘half-caste children’ – as official documents labelled this group – the government was keen to discourage the mixing of black troops and local women. It was proposed that ‘white women should not associate with coloured men. It follows then, they should not walk out, dance, or drink with them’.

These and other government suggestions were collated under the heading, typed in red ink: ‘MOST SECRET’ and ‘TO BE KEPT UNDER LOCK AND KEY’, primarily out of concern that aligning themselves with American policies of racial segregation would cause outrage throughout Britain’s colonies, where millions of black and Asian men and women were fighting on Britain’s behalf 2. The War Office decreed that the British Army should lecture their troops, including the women of the Auxiliary Territorial Service, on the need to keep contact with black GIs to a minimum 3.

In contrast, attitudes of the British public toward the black troops were initially very favourable. Reports from the Home Intelligence Unit (set up in November 1939 to monitor British morale) frequently mentioned people’s appreciation of ‘the extremely pleasing manners of the coloured troops’ 4. However, when British women started having relationships with black GIs there was voiced disapproval, with the Home Intelligence Report in August 1942 noting: ‘adverse comment is reported over girls who “walk out” with coloured troops’ 5.

If women in relationships with black GIs went on to have children, they generally faced a barrage of criticism. By October 1943 the Home Intelligence Unit was noting people’s rising concern about ‘the growing number of illegitimate babies, many of coloured men’ 6.

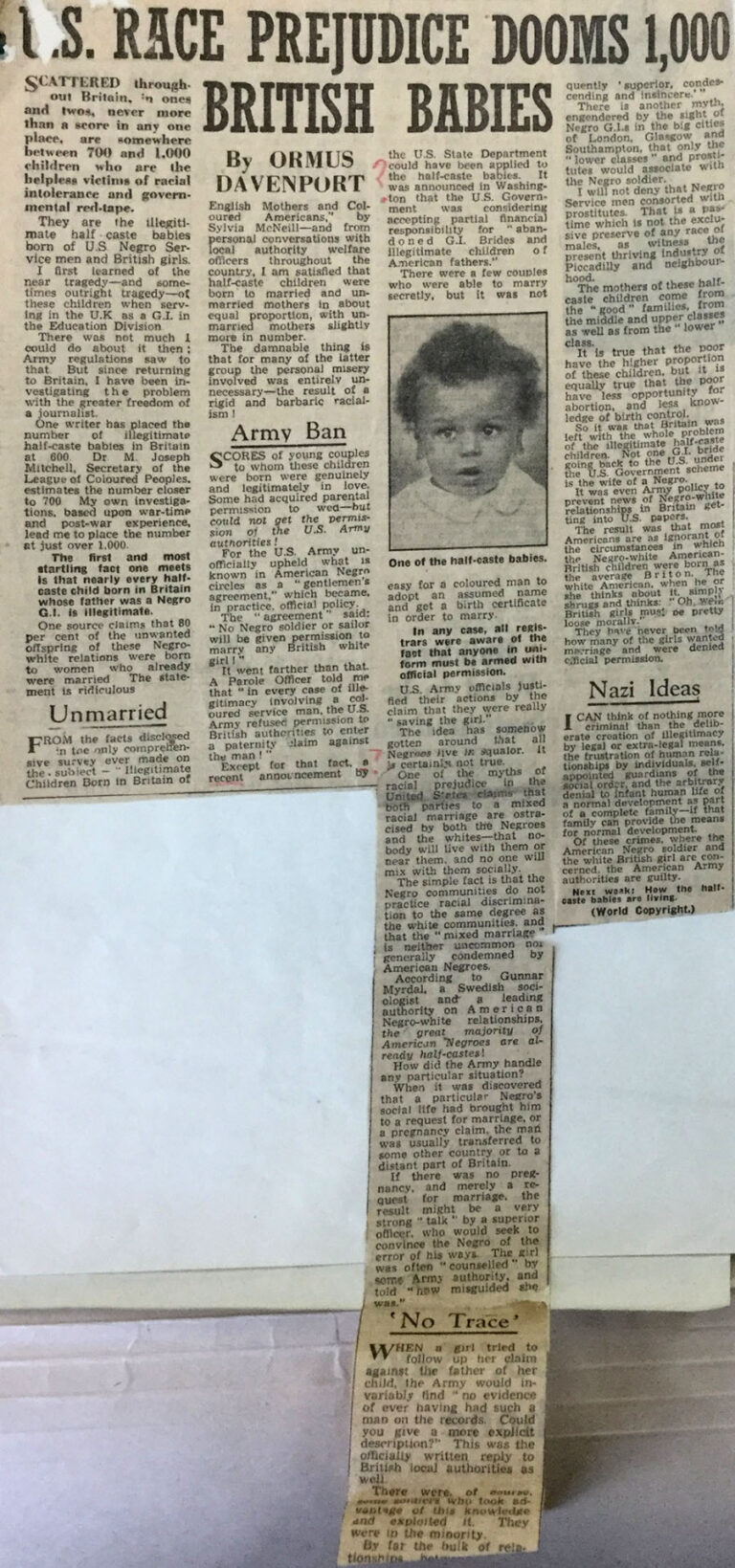

It is estimated that approximately 2,000 ‘brown babies’ were born in Britain during the war and nearly all of them were illegitimate. (‘Brown babies’ was the term given to these children by the African-American press). Every American serviceman had to receive permission to marry from his commanding officer (who in the UK were nearly all white) and avoidance of this permission was a court-martial offence. But for a black GI wanting to marry a white British woman, permission was invariably refused. According to black former GI Ormus Davenport, writing after the war, the US Army ‘unofficially had a “gentleman’s agreement” which became in practice official policy. The agreement said “No negro soldier or sailor will be given permission to marry any British white girl!”… Not one GI bride going back to the US under the US government scheme is the wife of a Negro’ 7.

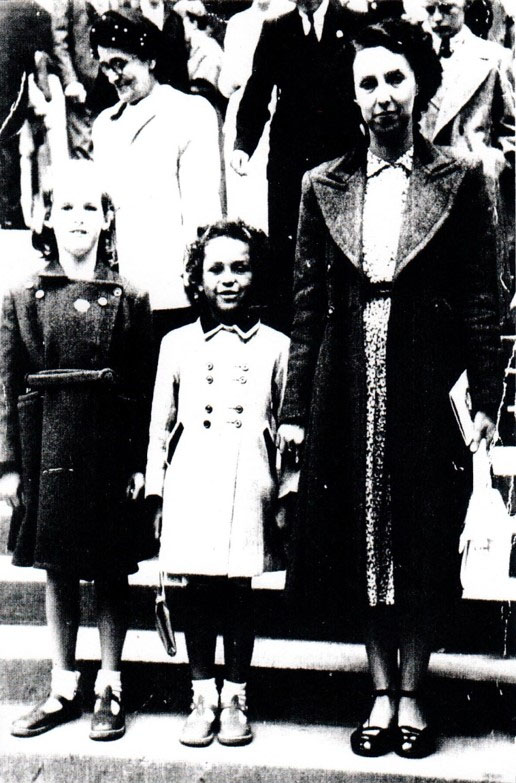

Nearly half of these babies were given up to local authorities or children’s homes, such were the difficulties and pressures facing the mothers: the stigma of having an illegitimate and ‘coloured’ child, and the fact that between a third and a half of the mothers were already married.

Many such babies born in Somerset were taken in by the local council and placed in a temporary nursery called Holnicote House, a National Trust property that had been requisitioned during the war by the council. Mothers who relinquished their babies hoped that they would be adopted, but adoption societies were loath to take black or mixed-race children, deeming them ‘too hard to place.’ Given difficulties in finding adopters for these children in Britain, Somerset Superintendent Health Visitor Celia Bangham was keen to arrange their adoption by their putative fathers, near relatives or other ‘coloured’ families in the US.

On 13 December 1945, the Home Secretary, James Chuter Ede, met with Miss Bangham and Victor Collins, MP for Taunton, to discuss the US adoption possibility. Chuter Ede was unenthusiastic: he worried about ‘the appalling discrimination made in many parts of the US against coloured people’. He also explained the legal position on adoption: under British law (the 1939 Adoption Act) children were only allowed to be sent abroad to live with British subjects or relatives. African-American couples who came forward to adopt were thus excluded from consideration, and since they were only deemed ‘putative’ fathers (there was no DNA testing for paternity until the 1960s), the black GIs were not considered to be relatives 8.

By December 1947 however, the Home Office and the Foreign Office had agreed to allow some children to be adopted in the US. The policy applied to ‘coloured’ children only, according to the Foreign Office, since white children were ‘an entirely different problem’ 9.

In what way they were ‘an entirely different problem’ was not spelt out. However the Home Office became worried about this overt exclusion of white children: there was ‘the need to avoid any suggestion that we in this country are trying to get rid of the coloured waifs left behind by the American occupation’ 10.

Yet getting ‘rid of the coloured waifs’ appears to be precisely what they were intending. Adoption by Americans was thus possible in 1948 but the border closed again in 1949, an official statement of explanation stating: ‘any implication that there is not a place in this country for coloured children who have not a normal life would cause controversy and give offense in some quarters.’

Documents from The National Archives have been invaluable in helping piece together this overlooked piece of history in the British experience of the Second World War. However, being official accounts, they portray a very specific perspective.

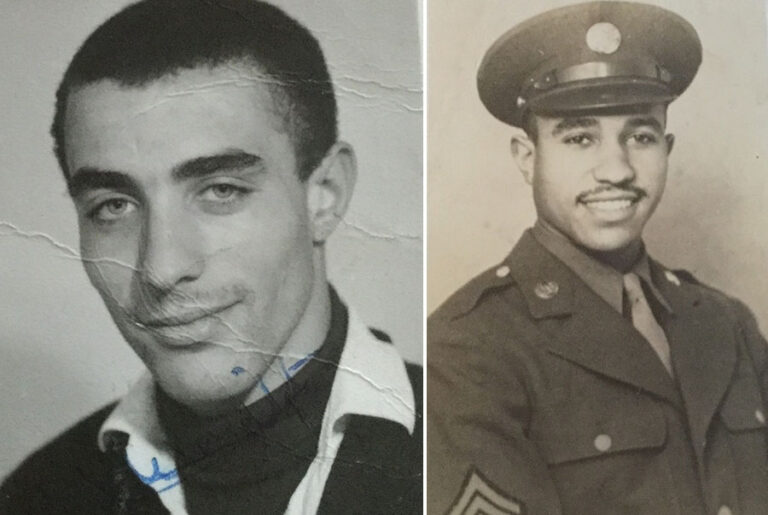

In order to understand the richer history, Professor Lucy Bland undertook interviews with many of these children, now in their seventies. The 60 accounts that she gathered together remind us that behind the government documents, newspaper articles and ‘outsider’ accounts through which what little history of the ‘Brown Babies’ has traditionally been told, are real people. The narratives reveal the ways in which so many of the children and their mothers, fathers and extended families experienced very painful and long-lasting personal, familial and emotional consequences due to the way how their mixed-race relationships and identities were perceived by those around them.

I stuck out like a sore thumb. I was just a reminder I suppose of what mum had done.

Yet also contained in their accounts are episodes and incidents of kindness and acceptance, alongside ongoing attitudes of perseverance and resilience.

[He said] ‘You’re my son aren’t you?’ I said, ‘Yeah.’… We got in the car and he said, ‘Are you gonna kill me?’… And I looked at him. And I just cried … And so did he. We just cried. It was … wonderful … I’d never cried.

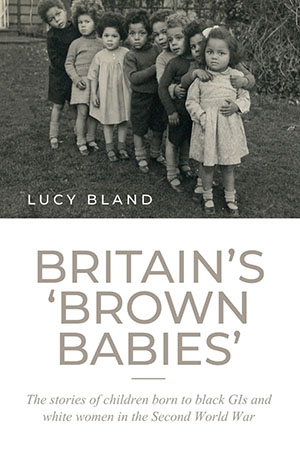

These fascinating and moving stories form the heart of Lucy’s book Britain’s ‘Brown Babies’: The stories of children born to black GIs and white women in the Second World War(MUP, 2019) as well as a current digital exhibition curated in collaboration with The Mixed Museum.

Both the book and the exhibition highlight the diversity and complexity of experience contained within the ‘Brown Babies’ history, alongside the way in which this history is rooted in a wider, long-standing history of the black and mixed-race presence in Britain itself.

To learn more, visit the ‘Brown Babies’ digital exhibition where you can contribute by sharing your reflections in the survey and creating digital postcards, or by sharing any personal history connected to racial mixing in wartime Britain in the exhibition’s community archive: www.mixedmuseum.org.uk/brown-babies.

Article written by Lucy Bland, Professor of Social and Cultural History at Anglia Ruskin University, and Dr Chamion Caballero, Director of The Mixed Museum.

Notes:

Lessons Learned: Trusting your Gut to Ecommerce Success2024-05-20 08:55

July 2010 Top Ten: Our Most Popular Posts2024-05-20 08:53

Guitar Retailer Offers Inventory on Facebook2024-05-20 08:46

Lessons Learned: Best Bully Sticks Thrives on Teamwork2024-05-20 08:45

4 Ideas to Cut Costs on Your Ecommerce Business2024-05-20 08:25

What Is a Denial-of-Service Attack?2024-05-20 08:22

Authorize.Net Exec Offers Fraud Prevention Tips2024-05-20 08:18

Order Fulfillment: ‘Kitting’ Can Dramatically Slash Your Costs2024-05-20 07:57

Site Search Complements Navigation, Says SLI-Systems CEO2024-05-20 07:43

Merchant Talk: Self-published Author Migrates to Ecommerce2024-05-20 07:04

eBay Expert and eBook Author Danna Crawford2024-05-20 08:40

SEO: Grow Multinational Sales With Geo-targeting “Signals”2024-05-20 08:32

Overseas Expansion: Tips from a Global Exec2024-05-20 07:41

Mobile Payment Systems Are Adapting, Developing2024-05-20 07:41

13 Little-Known Google Search Functions2024-05-20 07:36

Quick Query: Attorney Explains New FTC Blogging Guidelines2024-05-20 07:34

Quick Query: Attorney Explains New FTC Blogging Guidelines2024-05-20 07:20

Lessons Learned: Lori Karmel of We Take The Cake2024-05-20 07:13

Interview: Microsoft Exec on Future of Software2024-05-20 07:03

Order Fulfillment: ‘Kitting’ Can Dramatically Slash Your Costs2024-05-20 06:55