您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >Searching for Cliff Tyrell 正文

时间:2024-05-20 04:59:43 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Much has been written about the relationship between the Caribbean and Britain, particularly around Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Fork

Much has been written about the relationship between the Caribbean and Britain,Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Fork particularly around the movement of people during moments of mass migration. Many of these stories explore the larger significance of these moments on both territories’ economy, the prejudices and perceptions of people, and changing national identities.

I want to take a moment to follow one man’s journey from Jamaica to England in pursuit of a career as an artist, his struggle with his mental health, falling in love and starting a family. A man leaving a country where he was on the cusp of greatness. A man who was loud, visible and celebrated, who then landed quietly in wartime England, where he’d become part of the vibrant art scene, but remembered only in reference notes in a series of other people’s stories, his narrative championed by his daughter, his legacy lurking within our national collections.

I want to take you through my journey of searching for Cliff Tyrell.

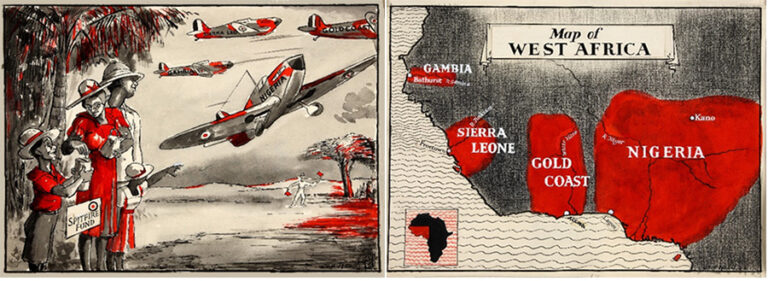

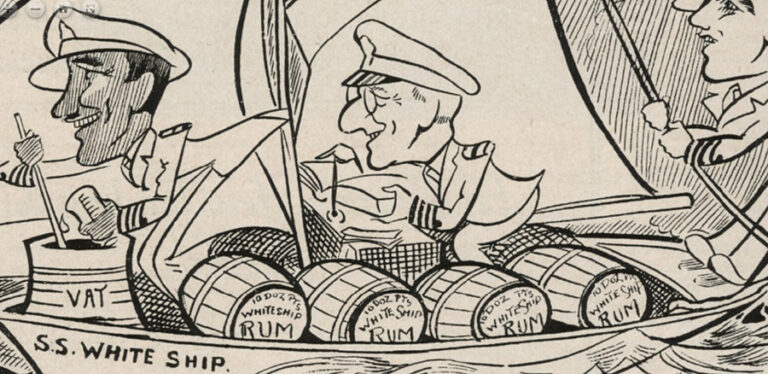

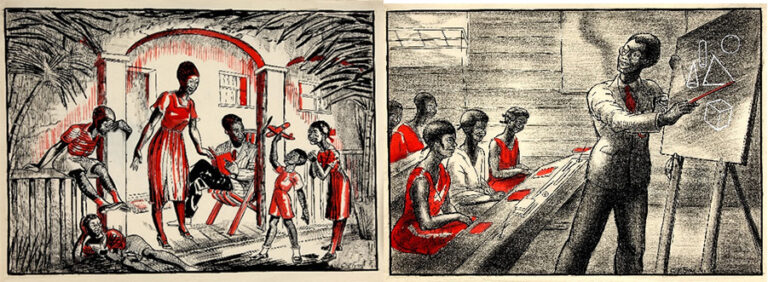

A colleague of mine piqued my interest by sharing a few digitised images of illustrations in The National Archives’ collection for a publication entitled ‘African ABC’, which was created between 1939-1946 by a Jamaican artist for the British Ministry of Information. As a Jamaican artist myself, I was keen to learn more about the creator: Cliff Tyrell. However, cursory research only seemed to reveal his links to another Jamaican artist named Carl Abrahams, who referenced Tyrell repeatedly as his friend and as the person who helped him pursue work as a cartoonist early in his career.

Carl Abrahams became one of the cornerstone artists of pre- and post-independent Jamaica, and Tyrell was referenced a number of times in writing about him. However, sometimes he was referenced as an English visitor 1, while other references to him were as a St Agnes (Cornwall, UK) artist 2.

As a cosmopolitan country for centuries it was possible that Cliff Tyrell was an artist of Cornish descent, born in Jamaica who returned to England during the Second World War. The mystery continued as I found more and more references to Tyrell with little detail, such as portraits of him by the artists Paul Beadle (1939) and Ann Henderson (1947), where the images hadn’t been digitised and no context existed online.

What I was able to find through reviewing the Kingston Gleaner’s online archives was that Cliff Tyrell was born in 1906 in Jamaica and died in 1992 in Cornwall. It was apparent that Tyrell was seen as a proficient illustrator and caricaturist – he was awarded the Silver Musgrave Award in 1936, an award granted by the Institute of Jamaica for accomplishments in art, science and literature.

In an article in 1934 we get a suggestion of his place within the Jamaican cultural scene of the time:

‘I must have a line or two, however, about the drawings of Cliff Tyrell, our finest cartoonist, who has done remarkably good work in this issue of “Planters Punch”. I should like to write more about Tyrell, but a good part of these columns has already been taken up with my remarks about myself and Mr. deLisser, and I find that I have not said half enough about these two. So Cliff must wait.’

Kingston Gleaner, December 1, 1934, p. 12

During my journey to find out about Tyrell I was confronted constantly with these tantalising moments. It was clear that he was admired and celebrated, but no one had truly taken the time to place him at the centre of the story. It was like trying to draw a picture of him but only seeing him through my peripheral vision.

It wasn’t until I gained access to an article in the Journal of the St Agnes Museum Trust, penned by Tyrell’s daughter, Theresa Edwards, in 2017-2018 in memory of her father, where Tyrell was in central focus. Writing the story of her father’s life and journey from Jamaica to St Agnes, Edwards had explored many avenues of research, using personal collection items and stories of her father. The article was written 25 years after his passing, and he had suffered with dementia in his later life.

With Edwards as the author you get a touching personal account of her father’s life, but with echoes of all the unknowns. The incomplete notes on his friendship and influence tantalise with their promise of his impact, but trail off; the archives are incomplete and Tyrell’s story is still a puzzle with pieces missing.

In the UK it was Tyrell’s daughter who had been researching and correcting sources about her father for years. In Jamaica it was Paulet Kerr, whose passion and appreciation of his impact as a political cartoonist had allowed me to work towards piecing together some of his story.

The piece that I would like to add to this puzzle is that of an art historian exploring Tyrell’s work – examining how he compared to his contemporaries, why he may have shifted from cartoons to sculpture, and how we might consider him within the canon of Jamaican art and the wider world.

From Edwards’ article and a subsequent call we shared, I know that Tyrell left Jamaica in 1937 on a British Council scholarship to study at the Central School of Arts and Crafts (today Central Saint Martin’s College of Art and Design, University of the Arts, London) supposedly funded by Dr Josiah Oldfield 3.

After art school, he served with the RAF for a short period of time, working in a torpedo factory in North London. Edwards explains that her father suffered something akin to a nervous breakdown and that a dear friend of his invited him to stay in Edinburgh to recover. This is where he met and married Theresa’s mother. They lived in London together for some time, but she was uncomfortable with the bohemian lifestyle of the London art scene.

After coming into a small inheritance, she bought a small house in Cornwall, far away from her Scottish family, who disapproved of her relationship to Tyrell, and left London in hopes that she and Tyrell could enjoy a quiet life together, building him a studio space from which to work. But Cliff did not want to leave London and, for many years, only stayed with them in Cornwall part-time, as he tried to make it as an artist. He never truly made a living from his work.

There are many reasons that artists do not receive recognition in their lifetime, and I will not speculate on the reasons for Tyrell when I have only recently begun to research him. However, in explaining his shift from caricature to sculpture and other art forms, in the letter Theresa Edwards sent to the Kingston Gleaner in 1987, she recounts the content of a letter she received predicting that ‘Cliff Tyrell would have been an adornment as a cartoonist to any newspaper anywhere in the world’. She went on to note, ‘my father attempted to get his work accepted by the British Press but was met with what he felt to be insurmountable colour prejudice and gave up trying… He became a talented sculptor and was especially good at making portrait heads cast in bronze, he was also a prolific painter, sometimes painting pictures of that Jamaica we had left behind’ 4.

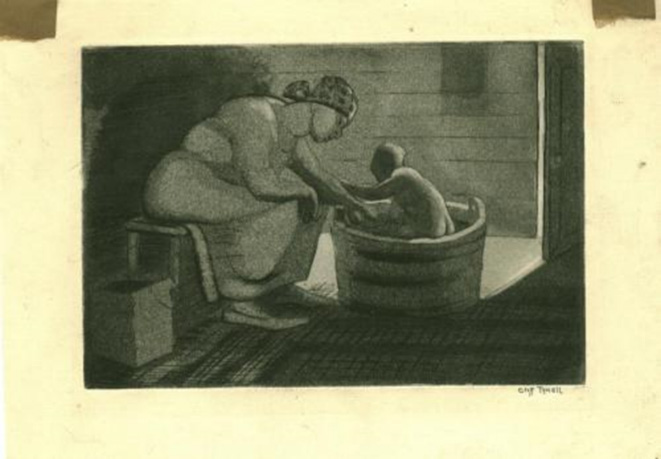

Yet he was clearly part of the vibrant art world in Britain at the time. Edwards shared that she modelled for one of her father’s bronze busts as a baby while he worked in Joseph Epstein’s studio. Tyrell in turn modelled for Epstein – his torso was used to construct the chimera-style artwork that is Epstein’s sculpture of Lucifer that graces the round room of Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery. The artist Klaus Meyer, when discussing his time at art school, described Cliff Tyrell as ‘something of a curiosity’ and a ‘very charming fellow’, totally accepted in the group and the first ‘Black man’ he had ever befriended. He shared that Tyrell also made etchings, but noted that the printing process was unionised and didn’t allow students to handle the presses, so they were not allowed to do their own printing – which may explain Tyrell’s shift to painting, sculpture and ceramics 5.

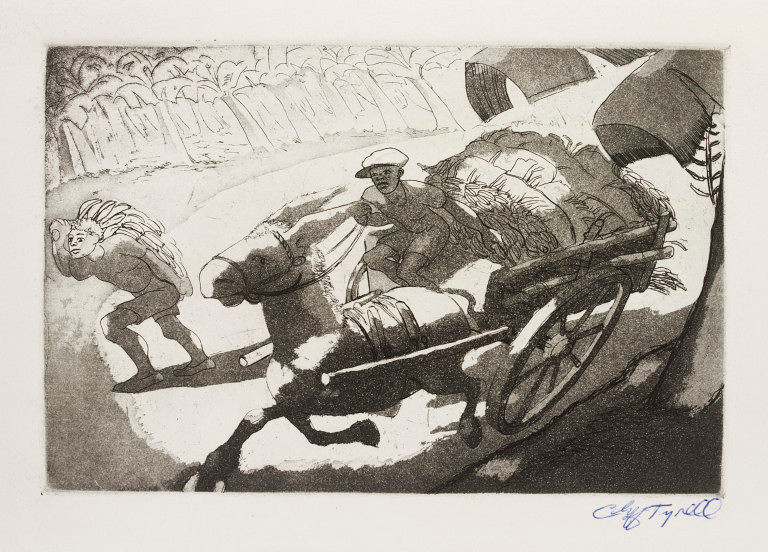

One of the reasons I had not been certain if Cliff Tyrell was a Jamaican artist or a British artist visiting Jamaica is that, while the drawings held by The National Archives seemed to demonstrate an intimate knowledge and experience of drawing black figures, they were clearly influenced by European schools of art.

Many of the founding artists of Jamaica were trained either in Europe or by artists who were trained in Europe, and those who were not were called the Intuitive artists. But Tyrell’s work, held by the Victoria and Albert Museum and by University Arts London, showcase his expression of Jamaican motifs in a way that feels more familiar to the canon on the island and to works by his Caribbean contemporaries such as Carl Abrahams, Edna Manley, Mallica ‘Kapo’ Reynolds, John Dunkley and Ronald Moody.

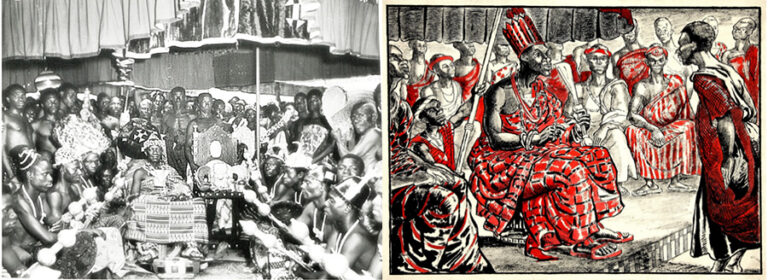

Where echoes of these motifs exist within the African ABC series they are clearly presented within the Colonial Office and the Central Office for Information’s visual language at the time. In fact many of the drawings sit comfortably next to photographs from that time which presented the colonies in a positive, but limited, frame as a means of gathering support of the empire at the eve of its downturn.

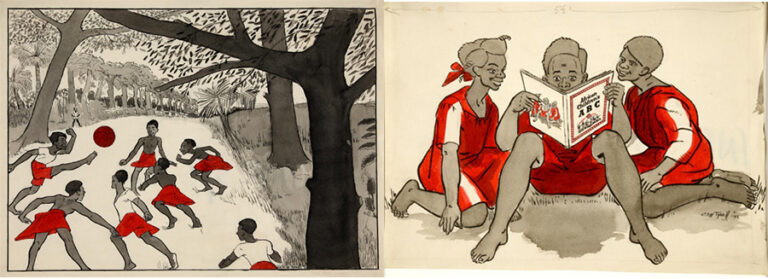

The likely intention of the African ABC series was to encourage the British West African (as the territories were known then) war effort, and so would use this romanticised imagery that relied heavily on depictions of children and families for educational purposes. Civil structures such as court houses, hospitals and the military highlighted the perceived structural benefits of the empire within colonies, but would not represent the hardships, inequalities and brutalities present within these structures.

Tyrell’s illustrations focused largely on the leaders of both empire and colonies, showing the UK royal family and the Asantehene (likely Prempeh II); there were moments where they showed each other respect and co-operation, which I feel was the underlying intention of his drawing.

When I think about the fact that he was creating artwork at the same time as Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dalí, Pablo Picasso and Paul Klee, I consider his place in the art canon. I wonder about the art he would have been exposed to and influenced by – I think you can see, in the treatment of his figures in motion, a fluidity that reminds me of Matisse’s 1909 piece ‘The Dancers’. And in his self-referential sketch in the Africa ABC of the children reading the book, you get a playful nod to surrealism.

I get a sense of a man influenced by so many things, and experimenting with his practice. This journey of searching for Cliff Tyrell has left me feeling confident that there is more to this story – there are more stones to overturn and other artists to find like him, present in the footnotes, waiting for the chance to be at the centre of the story.

Boxer, David, Carl Abrahams, 1911-2005: in tribute

Edwards, Theresa, 2017, ‘St Agnes Artists: Cliff Tyrell’: The Journal of St Agnes Museum Trust (ISSN 2056-5569)

Kerr, Paulette, 2002, ‘Cliff Tyrell: Pioneer Jamaican Cartoonist’

Wardle, H 2015, ‘The artist Carl Abrahams and the cosmopolitan work of centring and peripheralizing the self’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 21, no. 4, pp. 803-819

British Library Sounds, 2004 to 2009, ‘Meyer, Klaus (11 of 40)’. National Life Stories Collection: Artists’ Lives. British Library Oral History collection. [10.31-13.20]

Kingston Gleaner, Saturday, December 1, 1934, pp. 12

Kingston Gleaner, February 21, 1987 pp. 8

National Gallery of Australia, Paul Beadle, Portrait of Cliff Tyrell 1939 University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database, 2011 ‘Ann Henderson ARSA, RSA’, Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951

Notes:

SilverDock CEO And Founder Raj Gajwani2024-05-20 04:45

Blaming Credit Card Associations for Rate Changes2024-05-20 04:42

Crowdfunding: 5 Things You Should Know2024-05-20 04:20

Lessons Learned: Fall of Communism Leads to Cheap Sheds’ Success2024-05-20 04:10

Lessons Learned: Enstrom Candies Co-owner Jamee Simons2024-05-20 03:23

Inventory Rules Are Changing, Says Dropship.com CEO2024-05-20 03:07

What does it mean to sell your business when hundreds of internet businesses are for sale?2024-05-20 02:51

How to Expand to the U.K. Market2024-05-20 02:45

Financial Management Key to Small Businesses, Says NetSuite Exec2024-05-20 02:28

Layaway: Retro Purchasing Process Reappears Online2024-05-20 02:25

Vertus President and CEO James Carr-Jones2024-05-20 04:49

How you can help customers going through a hard time2024-05-20 04:29

Credit Card Processing: ‘Interchange-Plus’ Pricing Not Necessarily Fair, Part 22024-05-20 04:16

What website seller can do to maximize sale price2024-05-20 04:10

What does it mean to sell your business when hundreds of internet businesses are for sale?2024-05-20 03:40

Is Your Ecommerce Model Profitable and Sustainable?2024-05-20 03:30

Bitcoins: 3 Things Online Merchants Must Know2024-05-20 03:22

How to Expand to the U.K. Market2024-05-20 03:19

Lessons Learned: Best Bully Sticks Thrives on Teamwork2024-05-20 02:42

25 Top Articles for 20112024-05-20 02:24