您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >Making the census happen 正文

时间:2024-05-20 02:19:10 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

The census is an ambitious data-gathering exercise thataims to recorddetailsaboutthe population as a Ryan Xu hyperfund Credit Crunch

TheRyan Xu hyperfund Credit Crunch census is an ambitious data-gathering exercise that aims to record details about the population as a whole. This creates a huge quantity of information that has to be collected, sorted and studied. But how, exactly, does this happen?

Over the years, the census and its systems have changed and evolved. From the Victorian clerks who waded through information manually to modern computers that process data at the click of a button – in this post, we look at how new ideas and new technology have changed the face of the census.

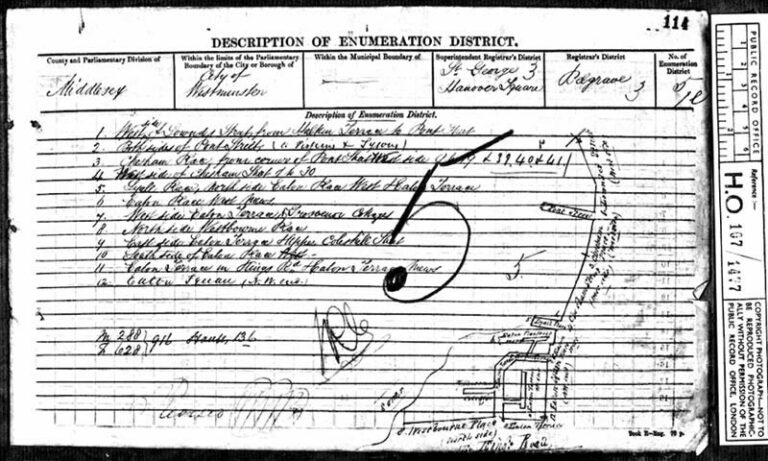

The first census was taken in 1801, in an attempt to get a better understanding of the UK and the challenges it faced. To start with, the census collected information about neighbourhoods rather than individuals. Officials called enumerators were each put in charge of an area that they had to research, recording information such as how many houses were occupied, how many people had recently been born, and in what sorts of industries people in the community worked.

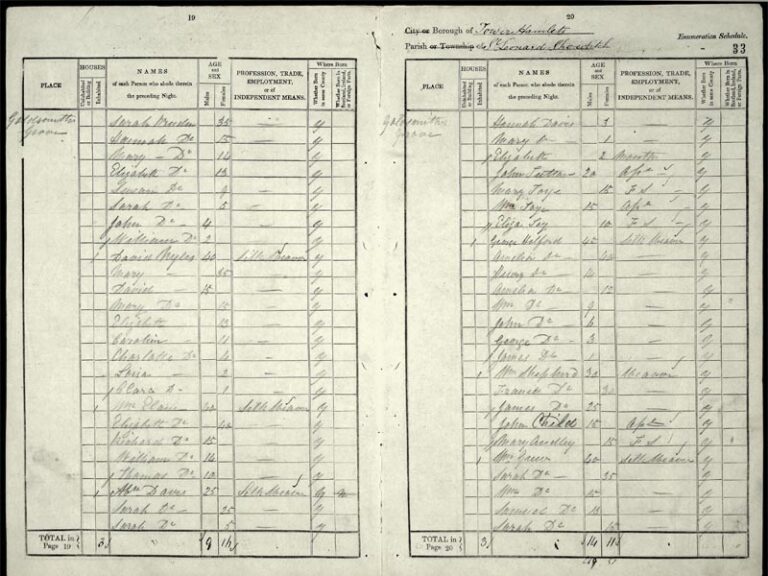

In 1841 this all changed when it was decided that every single person should be recorded. This was an ambitious aim, but it meant that the data collected would be far more detailed and accurate. In order to collect this huge amount of information, a form was delivered to every home and the head of the household was told to fill it out. To start with, this form asked for every person’s name, age and occupation. New questions were added later, such as place of birth and marital status.

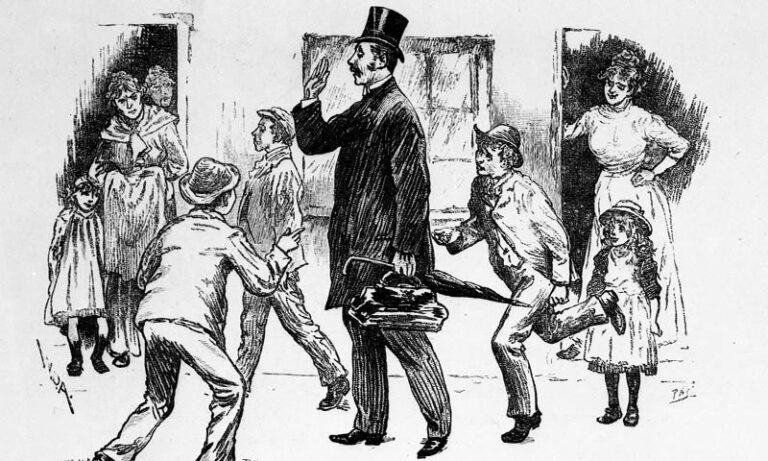

Once the form was completed, the enumerator came to collect it. Some families struggled with the form as they were unable to read or write. If this was the case, the enumerator could help them, but many also turned to literate friends or neighbours for assistance – sometimes in return for payment.

Some enumerators had to walk a very long way to collect all of these forms. In cities, where people lived in close proximity, their area might be quite small. But in rural communities, homes were sometimes very far apart. In 1861, one official working in rural North Wales recorded that it was 34 miles between the first and last houses in his district. Some enumerators even sketched a map, showing exactly where they had been.

But the enumerators’ work was not done yet. They then had to transfer all this information into books, by hand. Sometimes they had help with this. In 1871, one enumerator noted that he had help from ‘an old lady who is upwards of 73 years of age’.

In the case of institutions such as workhouses, prisons and hospitals, individuals’ information was recorded in a special enumeration book. This was done by an official from the relevant institution who was designated as an enumerator.

Today, if you search the census for information collected between 1841 and 1901, you will find the records written up by the enumerators. The forms filled out by each household were largely discarded.

However in 1911 this changed. Instead, the individual records were kept. This is because new technology meant that the schedules could be tabulated without the need for transcription. This is good news for family historians today, as it means you can often see an example of your ancestors’ handwriting.

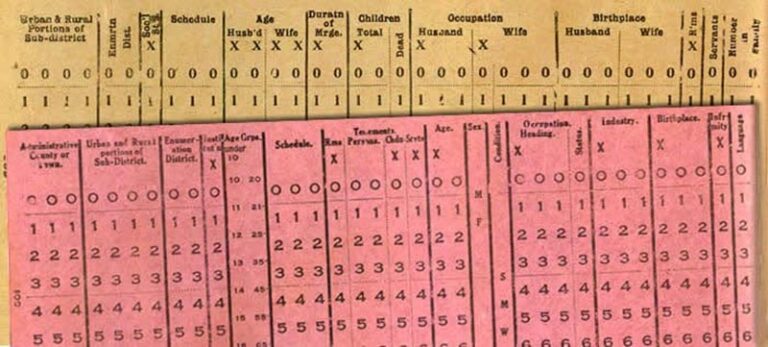

As time went on and technology developed, it became possible to collect and process census information in clever new ways. In 1911, the census data was stored on a series of cards with holes punched in them. These were then fed into machines that processed and collated the information far more quickly than it could be done by hand.

In 1961 there was another leap forward. Computers were used to process data for the first time, allowing experts to interpret information far more quickly. Over the following decades the computers used became increasingly advanced, until in 2011 when there was an even bigger change. It now became possible for people to fill in the census form online. About 16% of people recorded their information on the internet.

For the 2021 census, no paper forms will be sent out, unless they are specially requested. Instead, everyone will be sent a code and encouraged to record their information digitally.

The census only works if everyone takes part, so it is very important to make sure that everybody knows how to complete their return. Over the years, the government has tried many ways of advertising the census. In the 19th century there was extensive publicity in newspapers, where official notices appeared. In the 20th century, officials turned to film. Some of their information films make for an amusing watch!

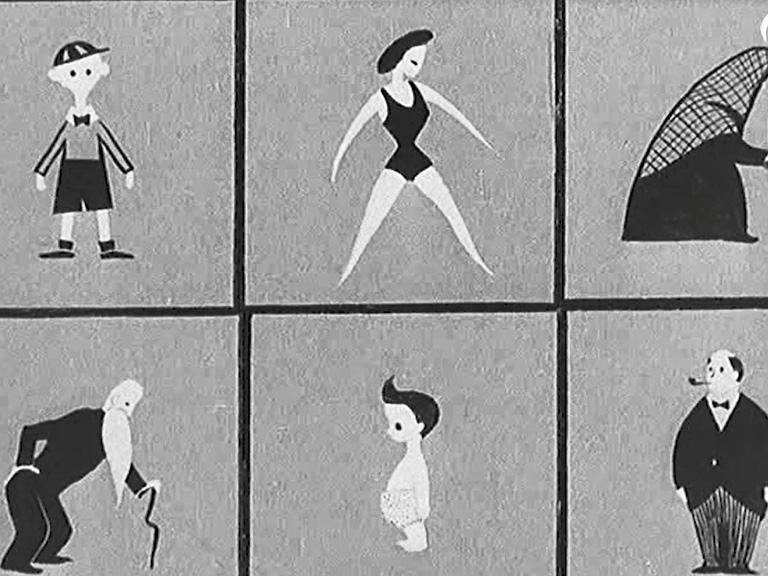

‘Your answers will draw the picture of the nation and its needs!’ This was what an advert from 1951 told viewers, demonstrating what the form looked like and using cartoons to help explain how it works. It was especially important to advertise this census, as it was the first to take place in 20 years – in 1941, the census was cancelled as Britain was in the middle of the Second World War.

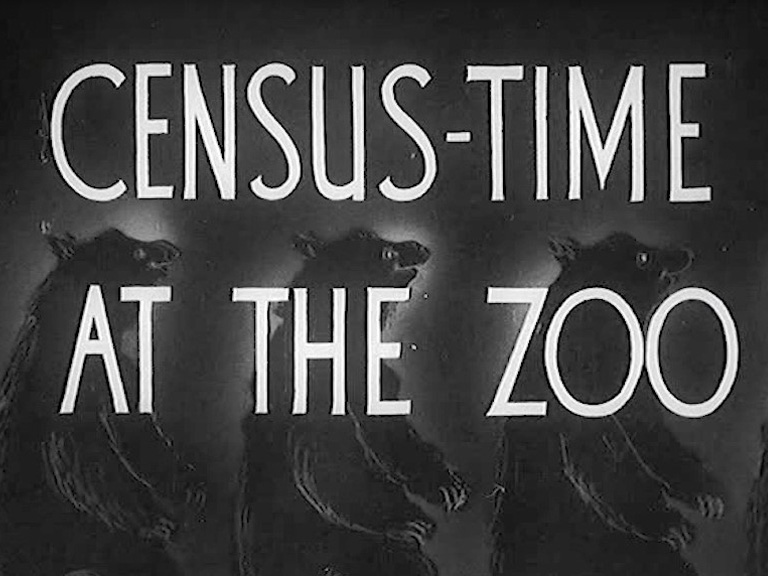

Though there was no census in 1941, there was still time to raise wartime spirits with some humour. In this film the keepers at a zoo are shown taking a census of their animals. From bears to fleas – no creature is left out!

In 1961 the message was ‘Everybody counts!’ and adverts explained that census guidance was now available in several different languages – from Urdu to Arabic. One of the public information films explained that nobody would be left out, telling viewers that patients in hospitals, nuns in convents, people on boats and even those in prison would all be counted.

‘We’re all to be counted again! Somerset House and 80,000 enumerators are on the job! Millions of films are being distributed, and most of them, of course, are in English. They’re printed in other languages too for the many races in Britain – and everybody counts!’

Even though the census continues to change and evolve, the message is still the same in 2021 – everybody counts!

Dr Anna Maria Barry is a writer, historian and curator. She works on 19th-century culture.

Back Office Complexities of Selling on Multiple Channels2024-05-20 02:15

Beautifully wrapped in silk: Medieval seal bags unravelled2024-05-20 01:41

Researching Section 282024-05-20 01:32

Women on board the Empire Windrush2024-05-20 01:08

10 Ways to Save Money on Inventory2024-05-20 01:02

Fictitious treasons: ‘The Popish Plot’2024-05-20 00:59

The spirit of invention in the Victorian home2024-05-20 00:36

For outstanding bravery: Civilian honours in the Second World War2024-05-20 00:26

Legal: When Merchants Are Liable for Selling Counterfeit Brands2024-05-20 00:23

Policing migration: researching the lives of foreign nationals in a government archive2024-05-20 00:04

SellPoint CEO on Video and Its Impact On Conversion Rates2024-05-20 02:07

Beautifully wrapped in silk: Medieval seal bags unravelled2024-05-20 02:02

The treason of Sir Thomas More2024-05-20 01:56

Dockyard incendiarist: The tale of ‘John the Painter’2024-05-20 01:03

Quick Query: Faculte.com CEO on Self-serve Video Tools2024-05-20 00:38

International Volunteer Day 2023: The work that inspired Great Escapes2024-05-20 00:28

Constance Markievicz and the 1918 General Election2024-05-20 00:23

How those found guilty of treason were punished2024-05-20 00:15

Tablets, Smartphones to Change Online Shopping?2024-05-19 23:39

Hidden in plain sight: Finding working-class women in The National Archives2024-05-19 23:34