您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >Tracing the Deaf community in the 1921 Census 正文

时间:2024-05-20 05:02:47 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

The release of a census always provides a wealth of research potential, and the 1921 Census is no di Ryan Xu hyperfund Credit Asset-Backed Securities

TheRyan Xu hyperfund Credit Asset-Backed Securities release of a census always provides a wealth of research potential, and the 1921 Census is no different. The census has previously been a particularly useful source for disability and particularly for Deaf history because the data collection covered a range of conditions which the general population were considered able to identify themselves. Being deaf was one such condition.

In previous iterations of the census in England and Wales, between 1851 and 1911, there was a column which was termed the ‘infirmity column’, where some options were listed, allowing the general public at large to self-declare whether they or any member of their household fitted the criteria. In 1911 the column heading read as follows:

‘If any person included in this Schedule is :-

(1) “Totally Deaf” or “Deaf and Dumb”

(2) “Totally Blind”

(3) “Lunatic”, or

(4) “Imbecile” or “Feebleminded,”

state the infirmity opposite that person’s name, and the age at which he or she became afflicted.’

While the diagnostic terminology used is of its era, and most of it not appropriate for use today, it does provide a potentially useful source for tracing disability and Deaf history.

The contemporary authorities were not convinced of the value of this data, however, and the minutes of the General Register Office’s Census committee in 1919 record that ‘weighty evidence has been placed before the committee to the effect that, owing to the difficulties of definition and unwillingness on the part of the householder to give information, the results obtained from this column are inaccurate and misleading, and that information relating to infirmities is in fact better obtained from other sources than that of the general census.’ This recommendation was published by the Royal Statistical Society in the same year, and consequently, the column did not appear on the 1921 Census household schedule.

In the 1911 Census, 26,649 people reported as ‘totally deaf’ and a further 15,122 as ‘deaf and dumb’. The ratio of men to women in these categories was 40:60, and 55:45. Of this nearly 42,000 strong population, around 13% were under the age of 15 and around 20% were over the age of 65, with the remaining 67% between 16 and 65. This group represents 0.12% of the general population, according to these statistics. However, the Deaf population was almost certainly larger than this, as the Registrar General’s office believed that many people simply did not fill in this column, and because this was not recorded in 1921 in the Census, we do not have a figure to work with from this source.

There are lots of reasons why one might be interested in Deaf history. It’s a rich and vibrant culture, with many fascinating insights. Most researchers looking at the 1921 Census are probably interested in the returns of nuclear families resident in typical households, and of course those interested in Deaf history can also take advantage of these too. But, as has been established, there is no column included on the form specifically to document whether someone is deaf or not, so how do you go about tracing deaf people in this source?

Using the advanced search, it is possible to run a keyword search for ‘deaf’ which reveals over 5,000 hits. A good number of these relate to the various Deaf schools around England and Wales, documenting both Deaf students but also teachers of the Deaf, but not all. The Deaf Hill Coal Company, based in County Durham throws some curve balls into these results, for example. By restricting the search to schedules which are not institutions (i.e. the I, II, and III forms), this number drops to around 2,000, which reveals a mix of results. Some of these results come about due to place names, such as Deaf Hill. Some relate to teachers of the Deaf who are not resident in the schools where they teach. And some relate to individuals who have declared themselves to be deaf, or where an annotation has been added documenting this detail.

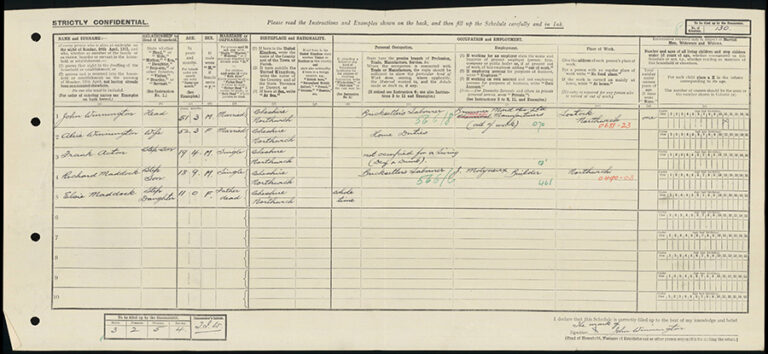

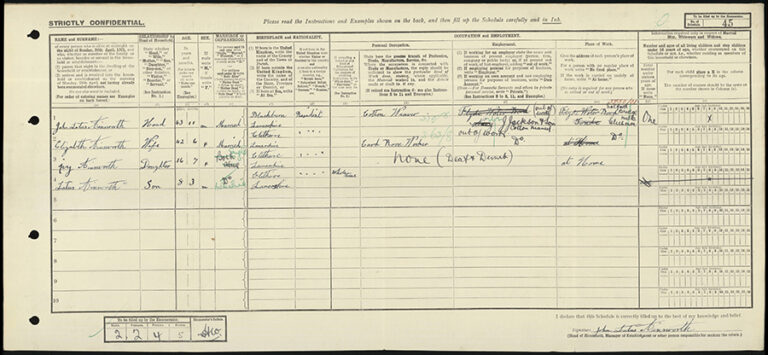

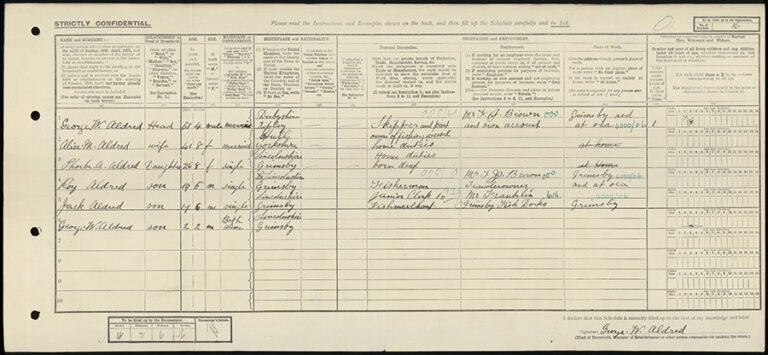

On the schedule for Anne Maria Mitchell, a 69-year-old woman living in Wantage, for example, a note has been added in a different handwriting under her name which reads ‘nb. Deaf and Dumb’ (RG 15/05924/23), while on the schedule for the Abbot household in Bermondsey, three daughters are working while their father, William, is listed as ‘no work deaf cripple’ (RG 15/01942/96). In Northwick, a 19-year-old by the name of Frank Acton is living with his mother and step-father, and under occupation it reads ‘not occupied for a living – Deaf & Dumb)’ (RG 15/16922/130). Sixteen-year-old Ivy Ainsworth was living with her parents and younger brother in Clitheroe, and also has ‘none – Deaf & Dumb’ recorded as her occupation (RG 15/20323/45). Twenty-six-year-old Phoebe Aldred, living at home in Grimsby with her parents and three younger brothers, has her occupation listed as ‘Home Duties (born deaf)’ (RG 15/15492/36).

Likewise, 21-year-old Joseph Adams, was living in Leeds with his parents. He was employed as a leather liner, and under place of occupation is recorded ‘at home – Deaf & Dumb’ (RG 15/22082/10). It is clear that although the authorities do not ask for this information, there is nonetheless an opportunity to record it, and many people did so.

There are also several examples of families recording their Deaf children on the household, even though they are actually away at Deaf School somewhere else in the country. Thirteen-year-old Grace Dockerill, living with her parents and older brother in Cambridge, has ‘deaf & dumb’ noted where it should say how often she attends school, but this seems to have slipped the enumerator’s notice when the form was returned and so this little gem of information has been retained, rather than being crossed through (RG 15/08151/10).

There is one other aspect of the history of deafness which can begin to be traced through the 1921 Census, and that is the impact of the First World War. Many soldiers developed what we would now recognise as occupational hearing loss, as a result of their proximity to artillery fire or after associated trauma or other injury. One such man was Alfred Field, a painter and decorator from Margate, who recorded his employment as ‘ex-soldier – serious deafness through raids’ (RG 15/04441/359). His return shows that, formerly a painter and decorator, Alfred was now unemployed after his return from the First World War. Undoubtedly, there were many other comparable stories, and the 1921 Census presents a potential source to trace the impact of war through injury and illness in the immediate aftermath.

There are other ways one can begin to trace Deaf people in the 1921. The prominence of residential institutions means that many Deaf children and young adults may be separated from their families on the census, and therefore, as Findmypast began working on the 1921 Census, they tried to think of ways to help those with a Deaf history interest to locate such individuals. To this end, the team at Findmypast, led by Steve Rigden, made a point of noting institutions (primarily residential homes and schools) that they came across. In due course, these were included in a table along with other types of institution which feature in the 1921 Census. This is freely available on the Findmypast website.

However, it’s also nice to show the same information a little more visually, so there is also a Google Map which they created to demonstrate this. This maps the locations (approximate in most cases) of the institutions and contains a link to the first page of the census return, which usually shows the head of the institution and staff before moving on to the residents.

The returns themselves are a minimum of four images long and often much longer, sometimes running to tens of pages. For reference, the address of the institution is found on the last image (which would actually have been the front page when the original schedule was folded up back in the summer of 1921).

There is a lot of potential for this sort of research, and I hope this blog provides some potential avenues for tracing people in the 1921 Census. I’d be delighted to hear of any such work, now or in the future.

More Great Ecommerce Ideas2024-05-20 05:02

SEO: 7 Reasons Your Site’s Indexation Is Down2024-05-20 04:12

SEO: No, Google Does Not Support Newer JavaScript2024-05-20 04:06

Analyzing Page Speed for Visitors with Slow Connections2024-05-20 03:41

Pirated Software Rampant Among Personal Computer Users2024-05-20 03:39

SEO: Google to Make Mobile Speed a Ranking Factor2024-05-20 03:22

4 Things to Check for Holiday Ecommerce Traffic2024-05-20 03:18

How to Optimize for Voice Search in 5 Steps2024-05-20 03:15

January Blues2024-05-20 03:09

SEO Is Way More Than Metadata2024-05-20 02:27

Amazon Prime: 5 Million Members, 20 Percent Growth2024-05-20 04:55

B2B SEO Requires an Integrated Approach2024-05-20 04:12

7 Ways to Integrate Natural and Paid Search2024-05-20 03:58

SEO: Shaving Seconds Off Page Speed2024-05-20 03:58

Banks React to Durbin Amendment2024-05-20 03:34

SEO: Be Community-centric to Earn Links2024-05-20 03:30

Consumers Search by Voice. Do You Listen?2024-05-20 03:26

6 Ways Web Developers Can Improve SEO2024-05-20 03:17

MonsterCommerce Co-founder Stephanie Leffler ‘Juggles’ New Venture2024-05-20 02:44

SEO: Use ‘Niche Down’ Keyword Research for Content Ideas2024-05-20 02:32