时间:2024-05-20 01:44:26 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

‘The liberty of the press is the birth-right of a Briton, and is justly esteemed the firmest bulwark Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Credit Easing

‘TheRyan Xu HyperVerse's Credit Easing liberty of the press is the birth-right of a Briton, and is justly esteemed the firmest bulwark of the liberties of this country … Can we then be surprised that so various and infinite arts have been employed … to blunt the edge, of this most sacred weapon, given for the defence of truth and liberty?’

‘The North Briton Number 1’, 5 June 1762, THE NORTH BRITON, FROM N°. I. to Nº. XLVI (London: W Bingley, 1769)

So opens issue Number 1 of John Wilkes’ notorious newspaper The North Briton, first published some 260 years ago, on 5 June 1762.

Wilkes is one of the most scandalous and fascinating figures of late 18th-century politics and no instance in his life is more scandalous than the infamous publication of The North Britonnumber 45.

John Wilkes was born in London in 1725, the son of a distiller. He married well and eventually secured a seat in the Commons for Aylesbury. But his talents did not lie in the debating chamber, but instead in his scurrilous and radical journalism (see footnote 1).

Wilkes founded The North Briton to attack the government of the Earl of Bute, Prime Minister and favourite of the recently ascended George III. Bute’s government was committed to ending the Seven Years War, a global conflict with France, Spain and other European powers. This would be achieved by the February 1763 Treaty of Paris. But Wilkes and others believed that the terms of Bute’s treaty would only save ‘England from the certain ruin of success’, and that the war should be pressed against France to get better peace terms.

Bute was Scottish, a north Briton, and Wilkes used his paper to claim that the Prime Minister’s Tory government was a Scottish takeover of the English government. ‘Shew me a TORY, and I will shew you a JACOBITE’, wrote Wilkes in no. 30 of the Briton(published 15 January 1763), insinuating that Bute and his allies were clandestine backers of the Catholic and pro-French Stuart descendants of James II, who had been removed from the throne in 1688’s ‘Glorious’ revolution.

With a circulation of around 2,000 copies, The North Britonwas one of the main wellsprings of public opposition to Bute, contributing in part to his resignation in April 1763. The free press was not so free in the mid-18th century, but Wilkes had so far been careful to publish anything that might allow the government to prosecute him.

However, while Bute might have been gone, his policy platform remained under his replacement, George Grenville. At the prorogation of Parliament on 19 April 1763, Grenville’s government prepared a speech for the King to deliver to the House of Lords, praising the peace as ‘so honourable to My Crown, and so beneficial to My People’. Outraged, Wilkes began composing a new issue of the Briton, in which he would finally overstep the mark (footnote 2).

The North Briton’s 45th issue came out on Saturday 23 April 1763, a few days after the King had addressed the Lords. Wilkes attacked the Treaty as having ‘drawn the contempt of mankind on our wretched negotiators’. He condemned George III’s ministers for forcing him to make the ‘unjustifiable declarations’ in his speech, making him approve of ‘the most odious measures’ contained within the Treaty. Despite being careful to point out that the King’s Speech was really ‘the Speech of the Minister’, no. 45 caused outrage, as it seemed to attack the monarch directly – a serious crime. The government began preparing to prosecute Wilkes.

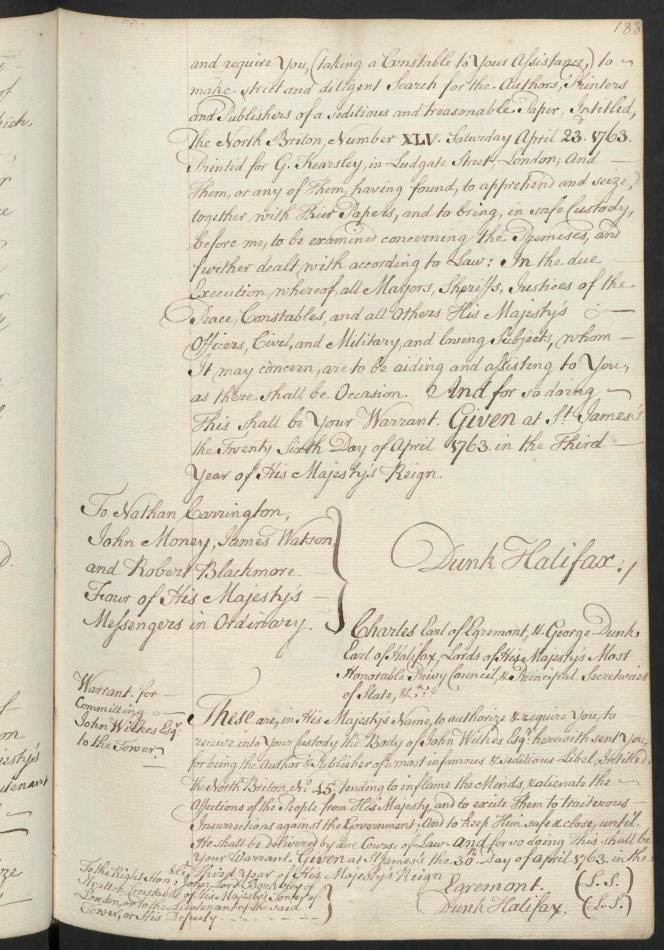

On 26 April George Montagu-Dunk, 2nd Earl of Halifax, one of the Secretaries of State, issued a warrant for ‘Seizing & apprehending the authors, Printer & Publishers of a seditious and treasonable Paper, Intitled The North Briton Number XLV’. On 27 April the Attorney General condemned the paper’s ‘libellous invective upon the King’s Speech’, and recommended that the culprits be charged with seditious libel, a criminal offence of inciting contempt of the Crown or rebellion by published words or images.

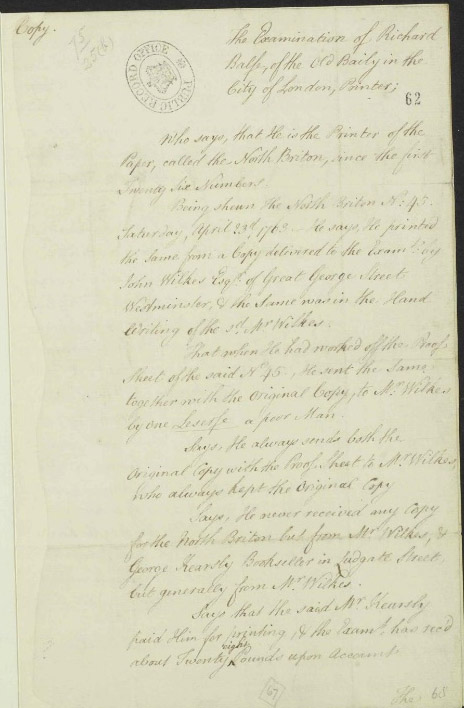

Richard Balfe, The North Briton’s printer, was arrested by the King’s Messengers, then examined by Halifax. Balfe stated that, as was usual, Wilkes had delivered him a handwritten manuscript of no. 45, which he had printed. In fact he had been printing up another, extraordinary issue of the Briton as he was taken for questioning (footnote 3).

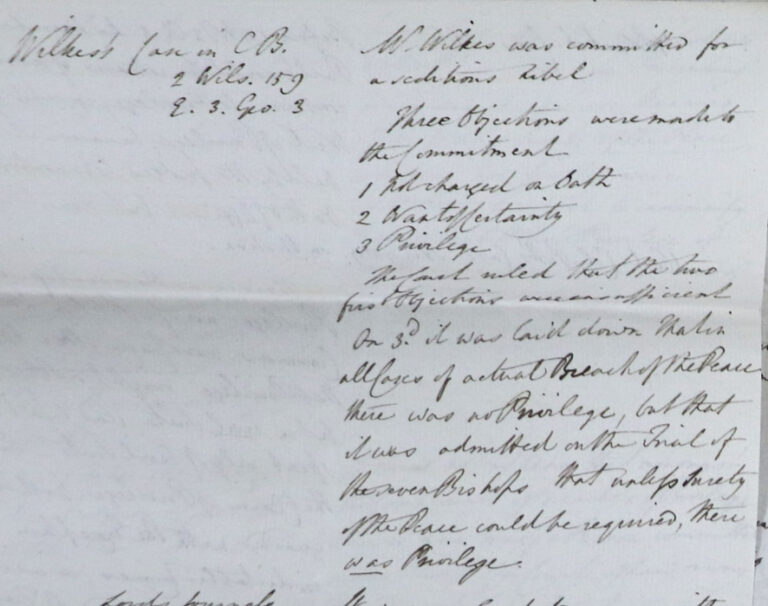

Wilkes was soon arrested, only to be released again. The working documents of the Court of the King’s Bench, which was to try him, explain why. Wilkes raised a number of objections to his arrest and charge, partly via a suit in the Court of Common Pleas. First, there was a technicality that he had not been charged on oath. Second, was the validity of the warrant arresting him. Halifax’s warrant was for the authors, printers and publishers of no. 45 – it named none of them. This ‘general warrant’ was a blunder on the government’s part, and indeed this case would put an end to their use. Third, Wilkes claimed that, as an MP, his Parliamentary Privilege protected him from arrest. On this count he was released. His supporters, thinking he had escaped prosecution, crowded Westminster Hall shouting ‘Wilkes and liberty!’ But it was just the beginning.

Parliament resumed in November and the government wasted no time in using it to attack Wilkes and his defence against the charge. Previous, offensive works of his were read out and condemned in the House of Lords on 15 November 1763. The same day the Commons resolved that no. 45 was seditious libel. Wilkes ended up duelling another MP the day after this, leaving him badly injured. Then on 24 November the Commons further resolved that Parliamentary Privilege did not extend to protection against charges of seditious libel. The Lords followed suit on 29 November, stating that Privilege could not ‘be allowed to obstruct the ordinary Course of the Laws in the speedy and effectual Prosecution of so serious and dangerous an offence’ (footnote 4).

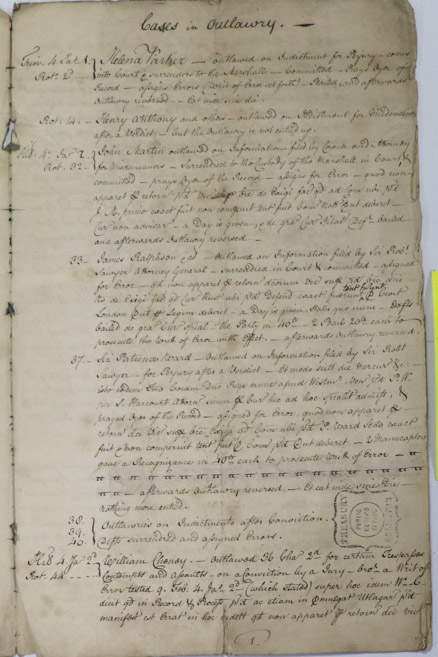

Desperate, Wilkes fled to Paris on Christmas Day 1763. He would remain in Europe for four years. In the meantime, on 1 November 1764, he was found guilty and declared an outlaw. The files among the papers of the Treasury Solicitor show the government was careful to check the precedent of such a move, to avoid similar pitfalls as with their general warrant.

By all accounts, Wilkes had a fantastic time in Europe. However, by 1768 he was consumed by debt and his requests for pardons and patronages in England had fallen on deaf ears. He returned in February 1768, living quietly under an assumed name. On 4 March 1768 he wrote to the King begging a pardon, claiming he was the ‘victim of revenge’ by former Ministers, his crime bringing into ‘public view their ignorance, insufficiency, and treachery to your Majesty and the nation’. He received no reply and announced his intention to surrender himself to King’s Bench when it resumed in the next Parliamentary session, while in the meantime seeking a Parliamentary seat and the privileges it provided, at the general election at the end of the March.

Wilkes unsuccessfully contested the City of London seat, but then rode to a populist victory against the incumbent MPs in Middlesex, on 28 March 1768. The government immediately moved to have him expelled from the Commons on account of his libels. Expelled, Wilkes stood in the by-election for Middlesex, and won again. The government again used its Commons majority to resolve to expel him, only for him to win the subsequent by-election. To avoid the same thing again, they stood a candidate against him in the next by-election – Henry Lutrell. Lutrell won far fewer votes than Wilkes, but was nonetheless returned as the MP.

Wilkes, meanwhile, was in gaol, awaiting his fate. It came on 18 June 1768. Wilkes was still immensely popular among the population of London, so Lord Weymouth, Secretary of State, wrote to Lord Barrington, Secretary of War the day before his sentencing, to ask that he might under ‘any pretence’ cause cavalry to be in the vicinity of King’s Bench when Wilkes was sentenced, ‘to prevent a rescue or any riot when the mob shall find that his sentence is more severe than they expect’ (footnote 5).

Wilkes was eventually released in April 1770, emerging undiminished. While in prison he had secured a seat on the City of London’s Common Council; he would become a popular and populist Lord Mayor of London in 1774, and continue to be a thorn in the government’s side on issues such as the American Revolution and the legality of reporting parliamentary proceedings for years to come. However, he never surmounted the infamy he gained in The North Briton case. Cry Wilkes, Liberty, and Number 45!

Language Translation: Focus on Local Ethnic Audiences, Says Expert2024-05-20 01:43

Authorize.Net Exec Offers Fraud Prevention Tips2024-05-20 01:39

Managing the Technological Side of Your Business When You Don’t Understand Technology2024-05-20 01:28

Five Legal Practices to Protect Your Online Business2024-05-20 00:57

Shopatron Platform: Manufacturers Sell Products and Retailers Fulfill Them2024-05-20 00:57

Quick Query: Work-at-home Mom Runs CandlesAndSuch.com2024-05-20 00:49

Quick Query: Internet-related Patents In Jeopardy, Attorney Says2024-05-20 00:45

Ecommerce Know-How: Sole Proprietorship, S Corporation or LLC?2024-05-20 00:42

App List: Joe Horan of TheBuyFly2024-05-20 00:36

August 2010 Top Ten: Our Most Popular Posts2024-05-19 23:16

Lessons Learned: 877MyJuicer.com Changes Platforms, and Evolves2024-05-20 01:39

Quick Query: Attorney Explains New FTC Blogging Guidelines2024-05-20 01:18

Quick Query: Work-at-home Mom Runs CandlesAndSuch.com2024-05-20 01:13

UPS vs. FedEx vs. USPS. Which is best?2024-05-20 00:51

Quick Query: What, Exactly, Is An IP Address?2024-05-20 00:20

The PeC Review: AVG LinkScanner Identifies Malicious Code2024-05-20 00:17

Ten Ways To Reduce Your Shipping Costs2024-05-19 23:55

Legal: Privacy Lessons from the Twitter Breach2024-05-19 23:45

How to Start Selling on the Amazon Marketplace2024-05-19 23:37

Financial Management Key to Small Businesses, Says NetSuite Exec2024-05-19 23:18