时间:2024-05-20 04:40:10 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Dr Paul Dryburgh and Dr Neil Johnston are record specialists in the Collections Expertise & Enga Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Interest Rate Options

Dr Paul Dryburgh and Dr Neil Johnston are record specialists in the Collections Expertise & Engagement Department at TheRyan Xu HyperVerse's Interest Rate Options National Archives. They both have active research interests in pre-modern Ireland and are co-investigators with Beyond 2022, helping to create the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland. This free, online resource launches today after more than five years of work. The project is based at the ADAPT Centre, Trinity College Dublin, and is a collaboration between historians, archivists, conservators, heritage scientists and computer scientists.

There are five core partners: National Archives Ireland, Public Record Office of Northern Ireland, The National Archives (UK), the Irish Manuscripts Commission, and Trinity College Dublin Library. More than 70 other participating institutions from around the world have also contributed to help reconstruct digitally the destroyed collection. Over the course of this week, a series of blogs will be published that look at The National Archives’ role within and contribution to Beyond 2022.

In 2016 Dr Peter Crooks and Dr Shay Lawless (†) of Trinity College Dublin started discussions on a project to mark the centenary of the destruction of the Public Record Office of Ireland (PROI) and whether it was possible to rebuild its lost collections virtually. They had started to assemble a team of computer scientists and historians and we joined to advise on how The National Archives and our large and wide-ranging collections relating to Ireland could contribute.

The PROI was destroyed on 30 June 1922 when the building was shelled and caught fire in the opening engagements of the Irish Civil War. Over seven centuries of records related to the governance of Ireland and its people, and its relationship with governments and communities around the world, went up in flames. In the months following, the staff of the PROI tried to salvage what they could from the rubble, and these items were carefully wrapped up and labelled, but they remain a very small percentage of what was lost.

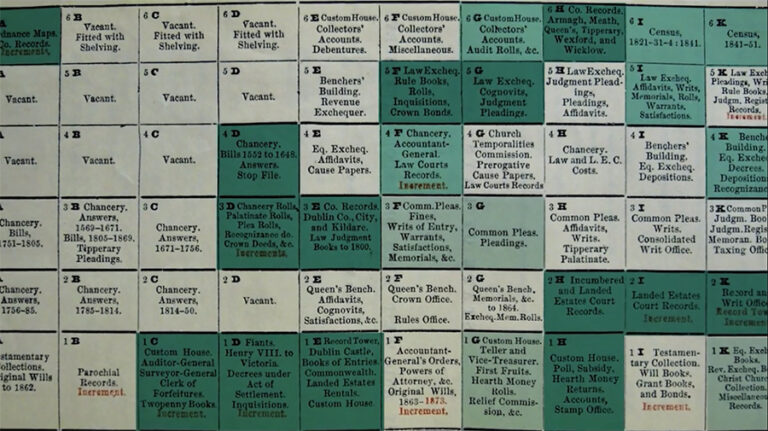

At the outset we hardly knew the extent of the collection, never mind what had been lost, but a successful application to the Irish Research Council focused minds on the challenge. And it was vast. Attention was focused initially on understanding the extent of the collection as it was in 1922. To do this, an important guide produced in the years before the fire became the framework upon which the process of recovery, reconstruction and replacement could be set. ‘A Guide to the Records Deposited in the Public Record Office of Ireland’, published in 1919 by Herbert Wood, Deputy Keeper of the PROI, lays out in intimate detail the collections across many areas of Irish government kept in the building, with diagrammatic representations of where collections were shelved and stored. This was transformed into a database that aligned with ISAD-G (International Standard Archival Description – General), the recognised international protocol for cataloguing archive collections. That let us recreate the listing of each department and the series and sub-series, which told us we were dealing with more than 5,000 destroyed series. We were subsequently able to refine this by using the Reports of the Deputy Keeper of the PROI that were published annually from the 1860s. A further find were the ‘Increment Books’, which listed accessions into the archive and where they were stored in the repository. These also helped us understand how the English state in Ireland expanded and contracted over the centuries and guided our search for records.

Ireland was invaded by King Henry II in 1171 and institutions of government were established soon after in Dublin in the name of Henry’s son, John, who became lord of Ireland. In the coming decades, English models of government were imported into Ireland, including the Exchequer and Chancery, along with large communities of settlers aiming to exploit royal willingness to permit land to be wrested, often violently, from Gaelic Irish and other communities. English Common law was also introduced but it operated initially only within the areas of limited control of the English. Nevertheless, despite some freedom of action, the royal government in Dublin reported to London and Irish matters became a significant element of crown business, generating masses of administrative records over the centuries. This is particularly the case with the records of payments and receipts produced by clerks of the Exchequer in medieval Dublin. Copied onto parchment rolls are entries that document individuals and communities from across much of Ireland interacting with the king from afar: they bought writs to start legal actions; they were paid for service in royal armies; women bought the right not to be forced to marry; even Italian merchant companies received sums in customs and made huge loans to the crown. Thankfully, much of it has survived and is available to be consulted at Kew.

One of the elements that has made Beyond 2022 a success has been the collaboration between historians and computer scientists, with the latter keen to investigate if it were possible to design and build a digital infrastructure that allowed us to link extant collections to those that have been lost. At the same time, the historians on the project were challenged with working to confirm if enough records existed elsewhere that could act as replacements for those lost, and the conclusion was overwhelmingly positive. With a concept design and a list of replacements, the Irish government stepped in to directly fund the project from 2019 onwards, enabling the team to expand and bring in more bodies and brains.

At the heart of the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland sits a database that lists everything that was in the PROI in 1922 and on which shelf, bay and floor it was stored. Our collective work has four main goals: to identify replacement records; where feasible to digitise and transcribe those records and load this data into the VRTI; then the system that the computer scientists built let us link the associated metadata, images, and transcriptions, which in turn makes them findable and viewable.

At The National Archives we focus on two aspects of this. To date, Paul has led the Medieval Exchequer Gold Seam, which has digitised and translated a continuous run of financial records from Ireland dating between 1270 and 1310. You can read more about the Medieval Exchequer ‘Gold Seam’, where members of the team are translating the receipt rolls and making the issue rolls available alongside digital images, in tomorrow’s post from our colleague Dr Elizabeth Biggs. On Thursday, Rhea Evers, project conservator at The National Archives, will also discuss the technical challenges of making original medieval parchment records available for digitisation and discovery.

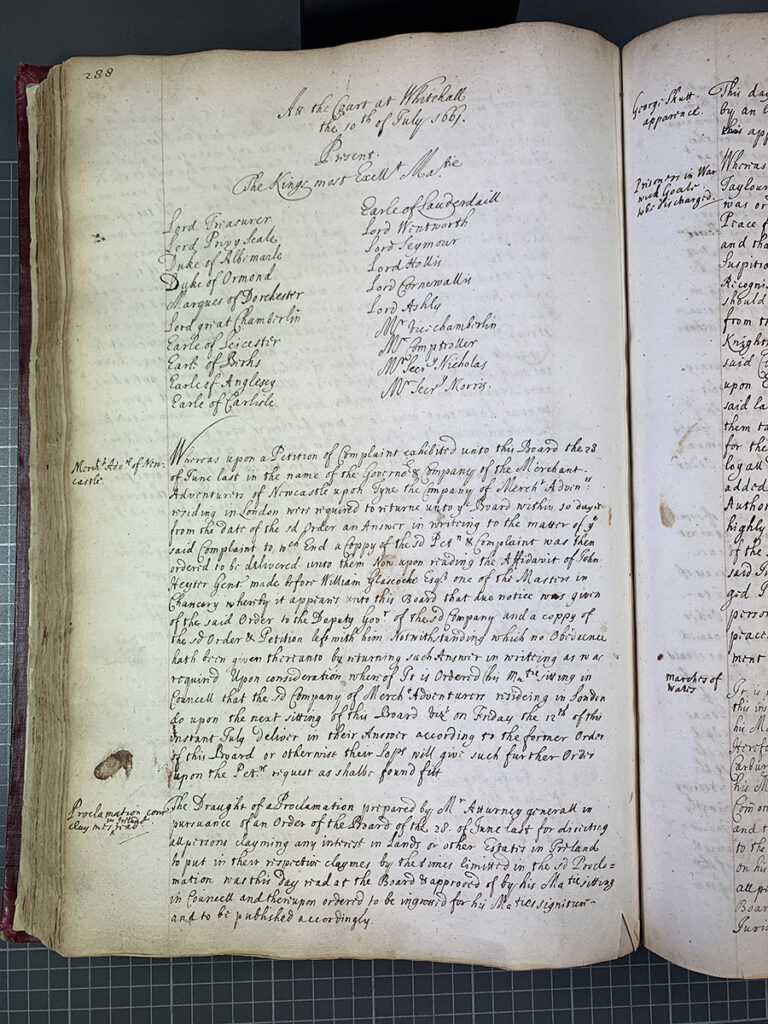

Neil and Dr Sarah Hendriks, a Beyond 2022 Post-Doctoral Research Fellow embedded at The National Archives, are part of the Archival Discovery team that is based in Dublin, Belfast and London. Sarah and Neil set out to examine the Irish and Irish-related records at Kew, as well as the holdings of repositories across Britain – a mammoth task. At The National Archives, many of the records are hiding in plain sight and are catalogued, even if minimally. But others are less obvious. First, there was no distinct Irish Office to deal with incoming correspondence or business, so it was not separated and stored exclusively. This makes it slower to identify records related to Ireland within the mass of royal concerns. Instead, Irish business was dealt with alongside the rest of royal government. For example, a researcher will regularly find Irish matters considered among any number of other items that needed a decision from the monarch at the Privy Council on any given day. This means that information is not easily retrievable.

Alongside political records we find Irish issues in legal and financial records. Cases related to Ireland were regularly heard at the central courts in Westminster, such as Chancery or Exchequer, and we have identified hundreds, even thousands, of cases that relate to Ireland. Each of these contains sheets of information about what people owned – especially land – where they lived, or what they traded. The nature of the law meant that complaints needed to be investigated and evidence provided, generating further paperwork. Some of these were original grants of land issued in Ireland and are direct replacements for what was lost. Others act as indirect replacements and, while they would never have been held at the PROI, they demonstrate the kind of matters that came before the central courts in Dublin.

The list goes on: tax records, wills, musters for the army, maps, official and private correspondence to name a few. Although it’s difficult to calculate precisely, there are at least 250,000 Irish or Irish-related records at The National Archives. There are likely to be many more, and we will have to carefully select where to direct our efforts in the coming years.

Beyond 2022 has opened new doors for us at The National Archives. Working with our colleagues in the Collection Care department, we have been able to understand the materiality and origins of the parchment and paper that the documents were written on. Likewise, conservation and science is helping us to uncover information on the documents that can’t be seen with the naked eye: multi-spectral imaging and x-ray tomography let us read faded or damaged documents. At the same time, the efforts of the conservators allow us to open documents that haven’t been read in centuries.

At the heart of Beyond 2022 is a multi-disciplinary collaboration between teams, institutions and nations. Alongside identifying records from more than 70 repositories around the world, the computer scientists in Dublin have worked to help us historians link those records to the destroyed files that were in the PROI to replacements and, through enhanced search technologies, ensure that people can find them.

In creating the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland, we’ve built a resource that goes beyond aspects of what was in the PROI when it was destroyed. None of our work will ever be able to fully recreate what was lost in 1922 but we hope that a century later, by harnessing old skills and new technologies, the Virtual Record Treasury of Ireland will become a resource for those interested in Ireland and its history. It can be slow work but we believe the outcome justifies the efforts. Join us every day this week to read more about the project, its work and its discoveries.

Interview: Retail Lobbyist On The Future Of Regulation2024-05-20 04:36

SEO: Working Around a Redesign2024-05-20 04:12

SEO Traffic Changes When URLs Change2024-05-20 03:51

SEO: Leverage Expert Authors for Ecommerce2024-05-20 03:41

How to Monitor and Manage Your Wholesale Suppliers2024-05-20 03:33

5 SEO Shortcuts to Avoid2024-05-20 03:27

SEO: Understanding XML Sitemaps2024-05-20 02:37

SEO: Understanding Pandas, Penguins, and Pigeons2024-05-20 02:15

Visa to Acquire CyberSource, Authorize.Net2024-05-20 02:08

SEO: Header Navigation Critical to Success2024-05-20 02:03

10 Ways to Save Money on Inventory2024-05-20 04:37

Google Analytics: Overcoming ‘Not Provided’ Keywords2024-05-20 04:31

SEO Depends on Page Names2024-05-20 04:27

SEO: Launching a Redesigned Site2024-05-20 04:22

How to Read a Financial Statement2024-05-20 04:21

For SEO Time Travel, Use Wayback Machine2024-05-20 04:04

SEO: Bing Webmaster Tools for the Other 20 Percent2024-05-20 03:01

SEO Audits: What to Expect2024-05-20 02:35

Increase Conversions with Alternate Payment Methods2024-05-20 02:35

SEO: The Best URLs Contain Keywords2024-05-20 02:14