您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >The displacement of Poles and their subsequent resettlement in the United Kingdom, 1939-1949 正文

时间:2024-05-20 03:32:30 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

A plethora of information exists in our collections on Poland and the plight of Polish refugees. Whi Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto ETF

A plethora of information exists in our collections on Poland and the plight of Polish refugees. Whichever series you choose to research,Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto ETF there is likely to be a reference to Poland’s turbulent history and the suffering of its people during the years covering the Second World War and beyond.

After the German and Russian invasions of Poland in September 1939, the Polish Government and many Polish soldiers, airmen and sailors escaped first to France and then to Britain, joining the Allies in the defence of the British Isles.

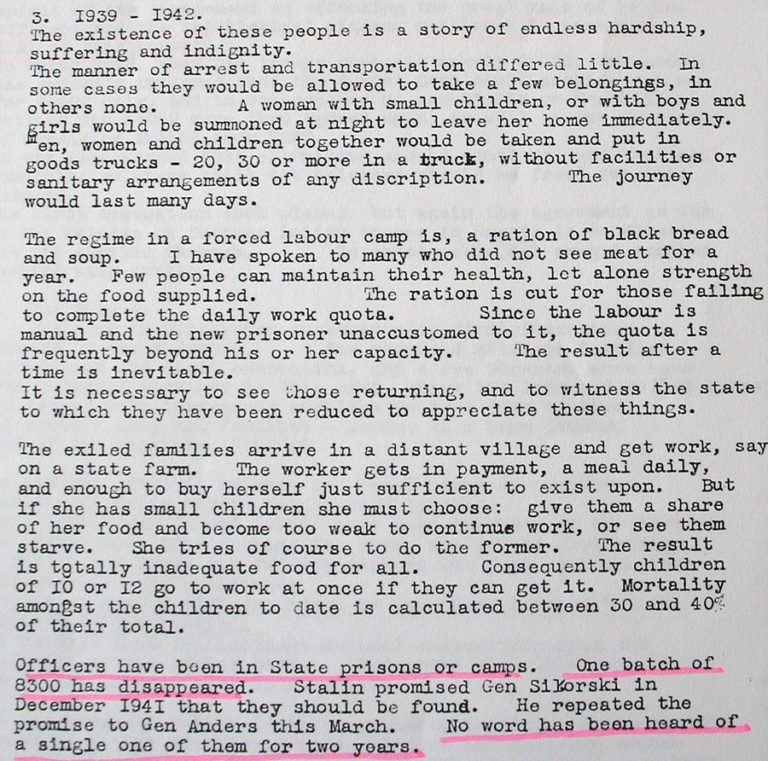

Stalin’s programme of ethnic cleansing in Eastern Poland began on 10 February 1940 and continued into 1941. Soviet statistics claim that nearly 280,000 families were uprooted from their homes, loaded into cattle trucks and taken to prisons and forced labour camps in Russia, but other sources claim that the numbers could be as high as two million.

Lieutenant Major Hulls, British Liaison Officer to the Polish commander General Anders, described the deportations of families to Siberia during Stalin’s ethnic cleansing of Eastern Poland. His report also questioned the disappearance on Soviet soil of Polish officers and intelligentsia, whose remains were discovered a year later by the Nazis in a series of mass graves 1.

Upon the signing of the Sikorski-Mayski Pact of July 1941, those soldiers who survived imprisonment were released and could join the newly formed Polish II Corps, which later fought in major Allied campaigns in North Africa, the Middle East and Italy. The soldiers and their families were required to find their own way to the nearest staging posts. From there they were directed to assembly points across Russia and Kazakhstan and evacuated in convoys to the port of Krasnovodsk. There they boarded tankers to cross the Caspian Sea to the transit camps in Pahlevi, before being moved to temporary camps in Tehran where they were segregated 2.

The soldiers were almost immediately sent from Iran to Iraq to join the Allied forces under British command. The Ministry of Labour and Social Welfare of the Polish government-in-exile in London organised where family groups were to be sent. These exiled families continued their refugee journeys, ending up in India, Africa, and other British colonies and protectorates. It is estimated that only around 119,000 Poles were evacuated, leaving the majority behind in Russia with no hope of rescue.

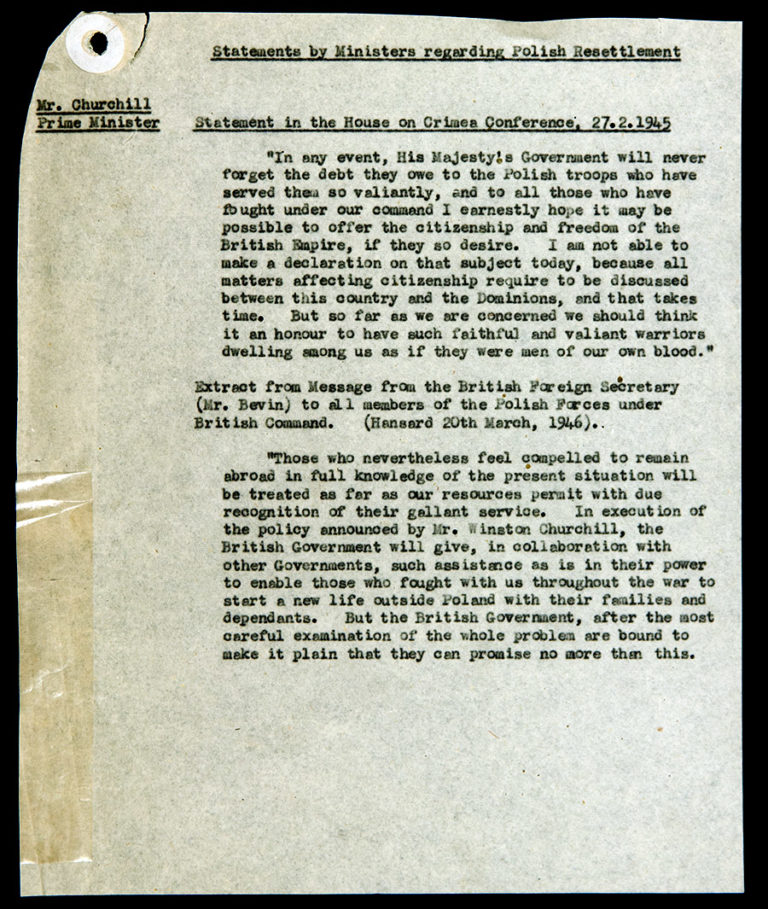

It is commonly accepted that the Poles were looked upon favourably during the war by the British; certainly the bravery of the Polish pilots and the land forces was acknowledged. But post-war attitudes of some groups were not all welcoming. Towards the end of the war, British policy towards Poland had changed quite drastically and no assurances about the future of Polish forces were in place. Churchill’s vision for the Polish troops was quite clear, as he stated at the Crimea Conference of February 1945. The British Foreign Secretary’s statement remained ambiguous 3.

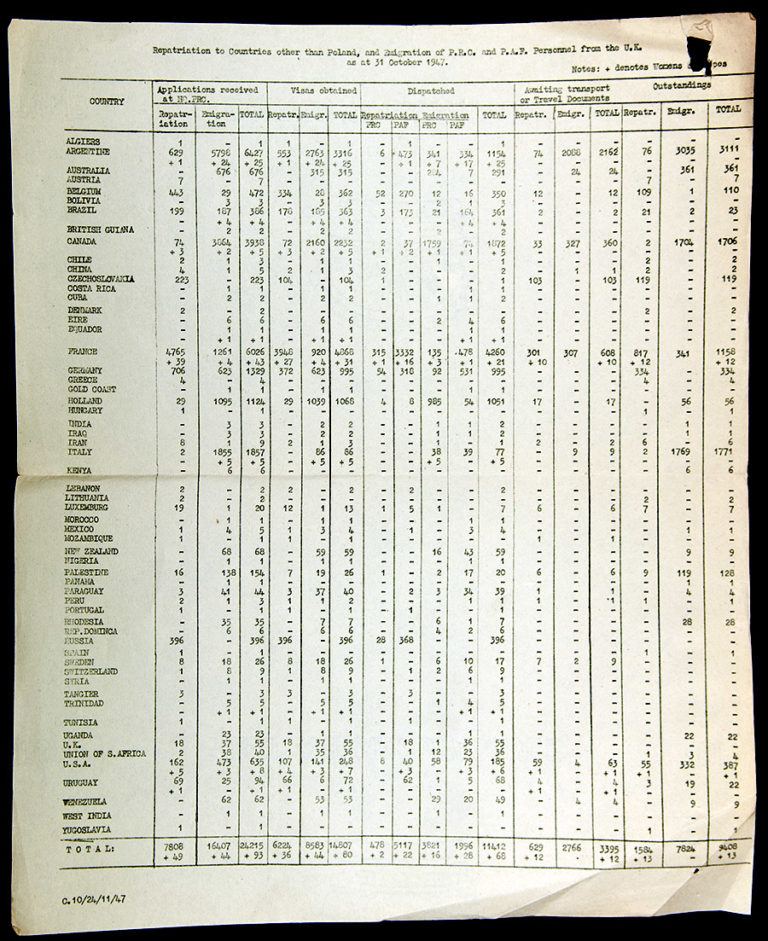

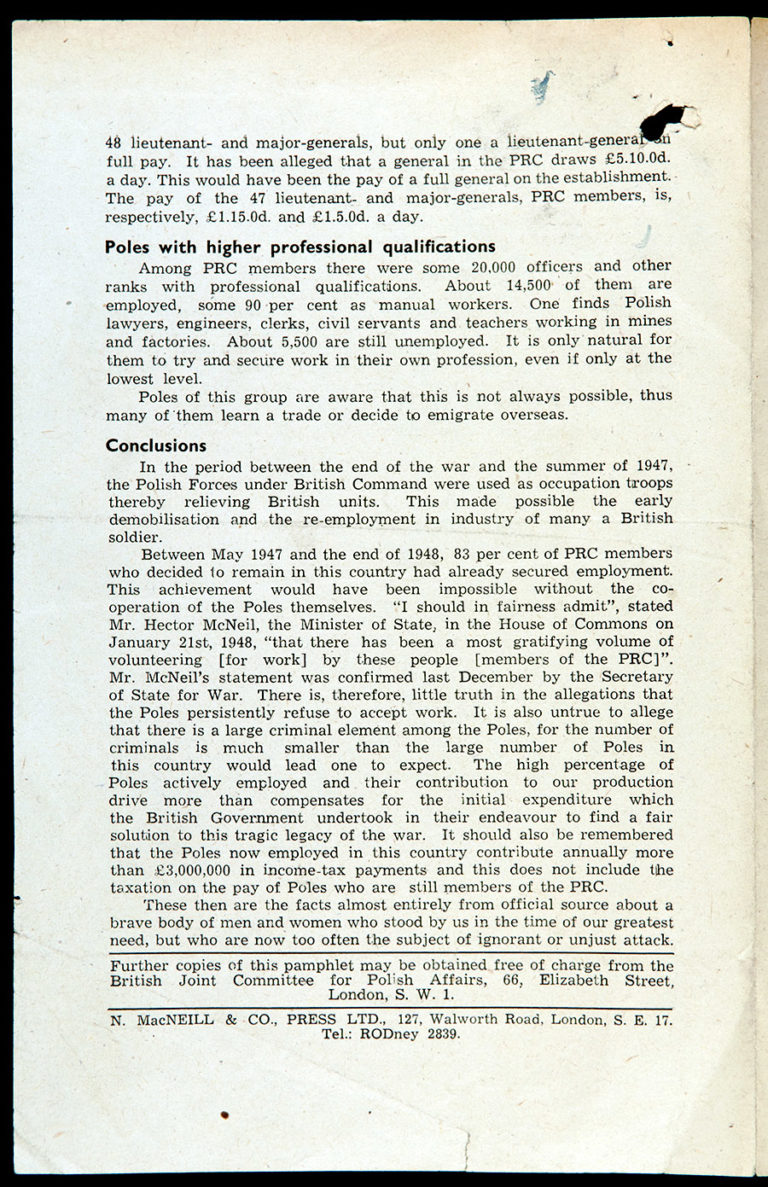

After the Second World War, the majority of Polish troops who fought alongside the British were unable to return to Poland. On May 22 1946, Anthony Bevan announced that the Polish Resettlement Corps was to be formed as a body of the British Army, enabling Poles who had fought under British command to join. The aim was to have all members demobilised within two years. The Polish Resettlement Bill was drawn up in 1946 and the Act was passed in 1947. It was the first ever mass immigration legislation passed by Parliament in Britain and allowed more than 220,000 Poles to remain in the United Kingdom. Around half chose to emigrate or were repatriated 4.

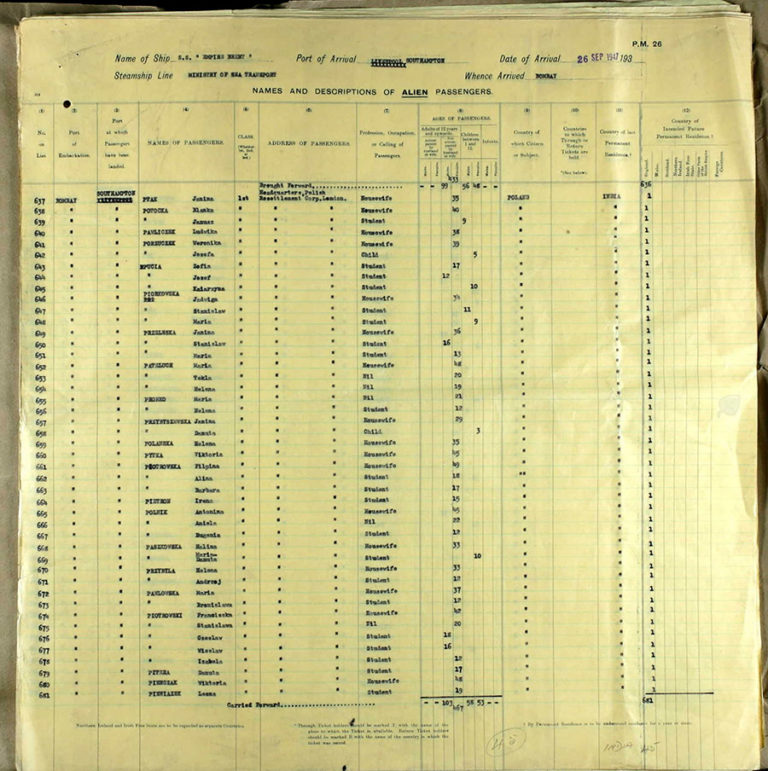

His Majesty’s government gave its approval for the War Office to make arrangements to bring to the United Kingdom the soldiers’ immediate relatives and dependants. These not only included the families scattered around British colonies and protectorates, but also those families who made it through to the British Zone in Germany following the liberation of the Nazi camps.

In July 1947, the Assistance Board took over the welfare of some 10-12,000 people who arrived on ships before the end of 1948 5. These families had no knowledge of English and special schools were established for the children, so they could learn the language and culture of their newly adopted country. By 1950 these schools followed the English curriculum and instruction was in English. The Polish youth were quick to absorb the language and adopt their new way of life.

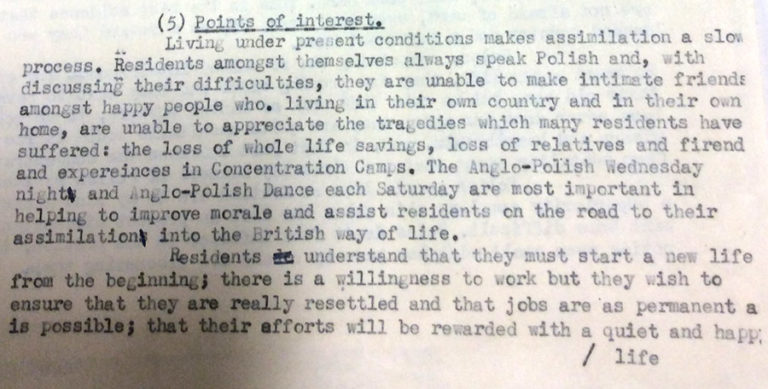

However, the government still had to persuade the British public that the Poles were an asset. Assimilation was not easy as English was still a second language to most and, although attending language courses was encouraged, communities would still speak in their native tongues, thereby slowing down the process of integration.

Attitudes of prejudice and distrust of the receiving community were associated with factors of a political, economic and emotional nature 6. Shortages of housing and rations fuelled negative public opinion, which was in turn influenced by government, press and, in particular, the trade unions. This led to a campaign, launched by The British Joint Committee for Polish Affairs, to inform the British public of the benefits of the Polish immigrants and also to remind them of the vital role they played as Allies 7.

The Polish Resettlement Corps was disbanded in 1949. During its short-lived existence, it brought about the reunion of families and the integration of displaced Poles into British society. For those Polish soldiers, airmen and sailors who fought with the Allies, it must have been welcome news when the British government allowed them to remain in the United Kingdom with their families, who had endured years of statelessness across the globe.

To mark Refugee Week we have made a bonus episode of our podcast On the Record at The National Archives, which is now available on the Archives Media Player and on podcast listening apps.

Subscribe: iTunes | Spotify | RadioPublic | Google Podcasts

You can also catch up on previous series in which have uncovered the true stories of famous spies and looked at protest – from the medieval Peasants’ Revolt to Black power in the courtroom. Most recently we have read famous love letters, and between the lines of less obviously romantic records, to discover the love stories of everyday people from the last 500 years.

PLEASE NOTE: Due to the age of this blog, no new comments will be published on it. To ask questions relating to family history or historical research, please use our live chat or online form. We hope you might also find our research guides helpful.

Notes:

Amazon Prime: 5 Million Members, 20 Percent Growth2024-05-20 03:20

The PeC Review: eStore-Opoly Game for Family Businesses2024-05-20 03:05

Order Fulfillment: ‘Kitting’ Can Dramatically Slash Your Costs2024-05-20 02:57

Merchant Talk: Etsy Seller Enjoys the Artistic Community of the Marketplace2024-05-20 02:56

Selling Products Online: What Legal Jurisdiction Applies?2024-05-20 02:54

Fractured Mobile Market Poses Challenges for Merchants, Developers2024-05-20 02:04

MonsterCommerce Co-founder Stephanie Leffler ‘Juggles’ New Venture2024-05-20 01:53

Financial Management Key to Small Businesses, Says NetSuite Exec2024-05-20 01:36

Jody Hartwig Of Netconcepts On Microsoft’s Live Search Cashback2024-05-20 01:27

The PEC Review: CRE Secure Eases PCI Concerns2024-05-20 00:50

What website seller can do to maximize sale price2024-05-20 03:25

Overstock.com CEO Patrick Byrne on Holiday Sales, Free Shipping2024-05-20 03:22

Quick Query: Shopping Cart Developer on PCI Compliance2024-05-20 03:07

Lessons Learned: 877MyJuicer.com Changes Platforms, and Evolves2024-05-20 02:33

Damon Schechter, CEO and Founder of Shipwire2024-05-20 02:24

Lessons Learned: Candle Retailer Regrets Custom Shopping Cart2024-05-20 02:02

Mobile Payment Systems Are Adapting, Developing2024-05-20 01:42

March Top Ten: Our Most Popular Posts2024-05-20 01:34

Quick Query: eHobbies CEO Kikkawa Offers Holiday-selling Ideas2024-05-20 01:16

The PeC Review: PayPal’s Website Payment Pro is a Good Value for Small Merchants2024-05-20 01:02