您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >‘Bandits, guerrillas, terrorists’: The role of the Central Office of Information during the Malayan ‘Emergency’ (1948-60) 正文

时间:2024-05-20 01:47:17 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Please note: This blog contains ideas, language and imagery from original records which reflect hist Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Relative Strength Index (RSI)

Please note: This Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Relative Strength Index (RSI)blog contains ideas, language and imagery from original records which reflect historical viewpoints and attitudes. Some may be considered offensive. However, we think it important to show them here as accurate representations of the record to help us understand the past.

The Central Office of Information (COI) is well known for its public information films. However, it actually employed a huge range of different media to communicate with the public. One important area it focused on was photography and over the years, between 1946 and 2011, it commissioned hundreds of still photographs to be used in the press and publications to serve the aims of different government departments.

After the closure of the COI, its photographs were not collected in one single archive. Since photographs were reproduced and republished in multiple media, copies of them can be found in multiple archives today. They can be found, for example, among records of government departments at The National Archives, but also in collections of COI material held by the Imperial War Museum. The same photographs can also be found printed in COI publications held by the British Library. In light of the 75th anniversary of the establishment of the COI this year, researchers at The National Archives and Imperial War Museums are working together to explore the connections between archival collections.

One of the COI’s largest clients was the Foreign and Commonwealth Office, and a key objective was to control how Britain’s actions abroad were seen and understood by the public. Maria Creech has been exploring this area in depth as part of an AHRC-funded collaborative doctoral PhD studentship with Imperial War Museums and the department of Journalism, Media & Culture at Cardiff University. Her research critically examines narratives of colonial counterinsurgency, focusing on photography generated around British and Dutch campaigns in Southeast Asia during the postwar period (1945-60). She is also co-founder of the Network for Developing Photographic Research (NDPR), which provides a platform for PGRs and ECRs working in any area related to photography.

In this blog, Maria outlines how she has traced a single photograph from the Malayan ‘Emergency’ (1948-60) through multiple archival collections, and explains how this can deepen our understanding of the conflict, the COI and its role in government propaganda. The story she tells reveals fascinating insights about how photography can be used as a tool to assert authority and define power relations, particularly in colonial contexts.

In 1948, Britain declared a state of ‘Emergency’ in Malaya, an area in Southeast Asia that was formerly a colonial protectorate and now constitutes Malaysia, Singapore, Sarawak and North Borneo. ‘Emergency’ was a strategic term the British used to describe their response to the independence movements that broke out across the Empire during the late 1940s and 1950s.

A region rich in natural resources, Malaya had been one of the most profitable territories in the British Empire. Occupation by the Japanese during the Second World War (1941-45) represented a distinct challenge to British authority in the region, sowing the seeds for an insurgency led by the Malayan National Liberation Army (MNLA), a communist guerrilla army, in the postwar years.

As the British government’s main PR and communications agency, the COI was involved in the management of public information and opinion around the Malayan ‘Emergency’ from the outset. British authorities had initially underestimated both the scale and strength of the insurgency in Malaya, assuming that the independence struggle was led by small disorganised groups of so-called ‘bandits’ and could be quelled in a few short years. By the early 1950s, it was evident to all parties involved that this was not the case.

While the colonial administration sought to discourage civilian support for insurgents ‘on the ground’ with the introduction of harsher governance measures (including curfews, stop-and-searches and forced ‘resettlement’), Whitehall responded with an intensified propaganda campaign that involved more aggressive use of psychological warfare tactics. The COI commissioned photographers to produce images intended for official and press use. Some of these appeared in pamphlets and albums created in collaboration with other government departments, such as the Air Ministry or the Colonial Office.

Tracing this COI-issued photograph across three government archives allows us to construct a clearer picture of Britain’s propaganda campaign and explore how imagery was used to communicate targeted messages about the ‘Emergency’ in Malaya to different readerships.

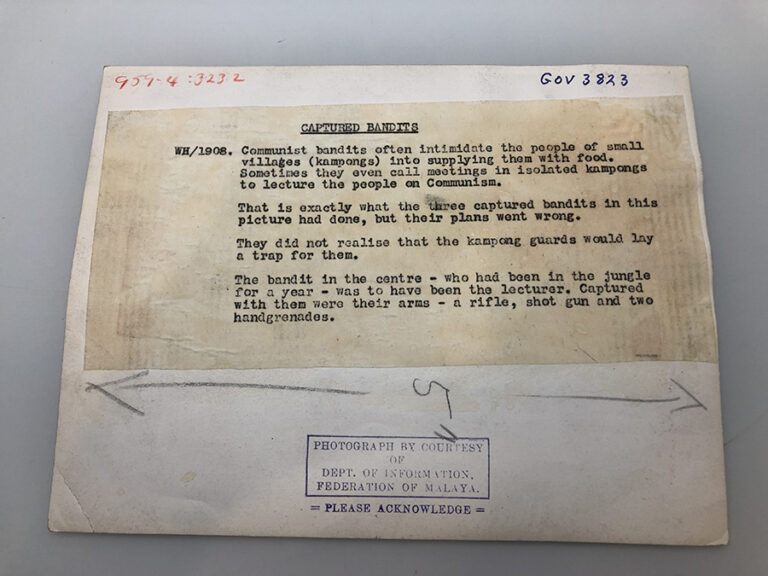

This journey begins in the vast photographic archive of Imperial War Museums, where the original print (GOV 3823) can be located within the COI Post-1945 Official Public Relations collection. It is a typical example of a ‘trophy’ photograph, a practice with well-established ties to military conquest, particularly in colonial warfare settings.

Taken under duress, a photograph of captured soldiers ordered to pose with their weapons could function as a souvenir, as evidence of British military superiority and, upon distribution, as a warning to insurgent armies still at-large. A press release attached to the back-side of the print, titled ‘Captured Bandits’, weaves a dramatic narrative around the individuals in this photograph, whereby they are cast as Cold War villains, who ‘often intimidate the people of small villages (kampongs) into supplying them with food’ and ‘lecture the people on Communism’, and the guards as heroes, who manage to outwit them and ultimately capture them by ‘layi(ng) down a trap’.

Without a stamp identifying the exact production date of this photograph, it is only possible to make an informed guess that it was produced in the late 1940s/early 1950s based on a few clues contained in the official description. The repetition of the pejorative term ‘bandit’ in the press release could imply some connection with ‘Anti-Bandit month’, a widely-publicised recruitment drive led by the British government which aimed to enlist ethnic Malays to the Special Security Forces.

The names of the individuals in this photograph are also absent from any accompanying written record, which isn’t unusual given the genre of this photograph and the tone of the press release, where they are assigned the role of caricatures standing in for a ‘common enemy’.

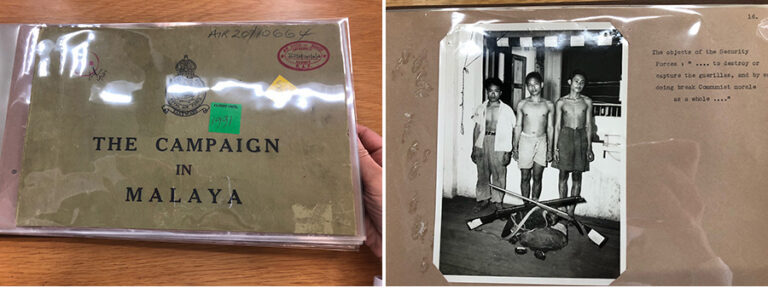

The same photograph appeared in an album produced by the Air Ministry in the early 1950s, titled ‘The Campaign in Malaya’ (AIR 20/10664), held by The National Archives. In this publication, there are no references to a backstory involving the laying of traps or lecturing villagers. Instead, the rather brief accompanying text states that one of ‘the objects of the Security Forces’ is ‘… to destroy or capture the guerrillas, and by so doing break Communist morale as a whole…’

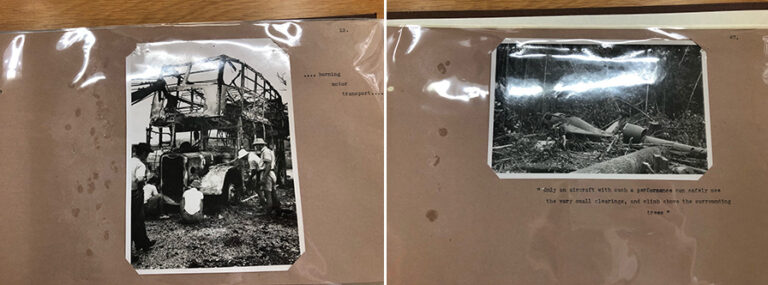

As the use of ellipses suggests, this description sits within a broader narrative that evolves as the reader turns each page. In previous pages, photographs documenting the insurgent army’s purported activities aimed at ‘terrorising the population’, including ‘ambushes of trains’, ‘burning motor transport’, ‘sabotaging Estate property’ and ‘slashing rubber trees’, feature as proof of a destructive and tangible enemy threat.

Situating our original photograph within this series helps shed light on the intentions of those involved in its publication. The imagery in this pamphlet is used to illustrate the connection between individual acts of destruction by insurgents and ‘Communist morale as a whole’, placing the local activities of the Far East Royal Air Force – such the ‘capture of guerrillas’ – within the broader context of the international Cold War.

An appeal of this kind sought to make explicit the contribution of the RAF to the broader struggle and, crucially, justify the expense of prolonged combat (an agenda that reveals itself in the final pages of the pamphlet, where the narrative transforms into a plea demanding that British taxpayers fund more sophisticated aircraft).

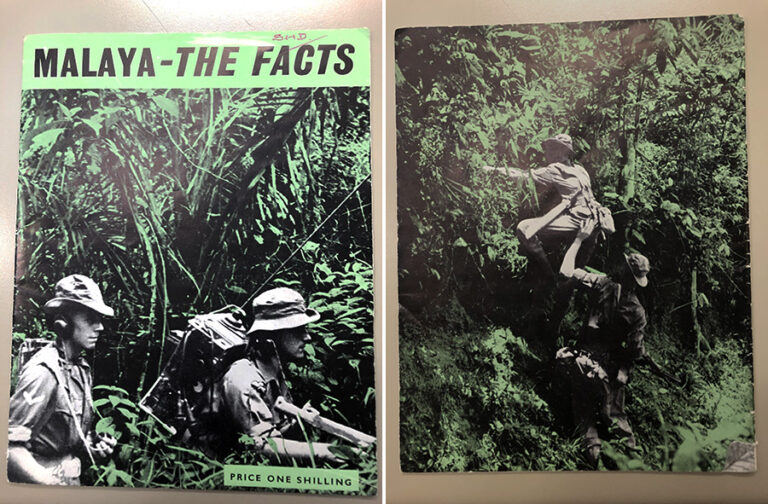

The photograph reappears in a pamphlet titled ‘Malaya: The Facts Behind the Fighting’ prepared by the Colonial Office in London in 1952. This copy belongs to the British Library (PF-192-34). Formulated in order to communicate ‘the facts’ about the Malayan ‘Emergency’ to the British public, information in the pamphlet is arranged in a Q&A format, as if to reconstruct a dialogue between an informed author and an inquisitive reader, and is illustrated with photographs.

The bizarre colourisation of this black and white cover imagery nods to a theme that comes to the surface within this pamphlet: that ‘facts’ are easily manipulated, particularly in irregular warfare contexts, where it matters which side is offering them.

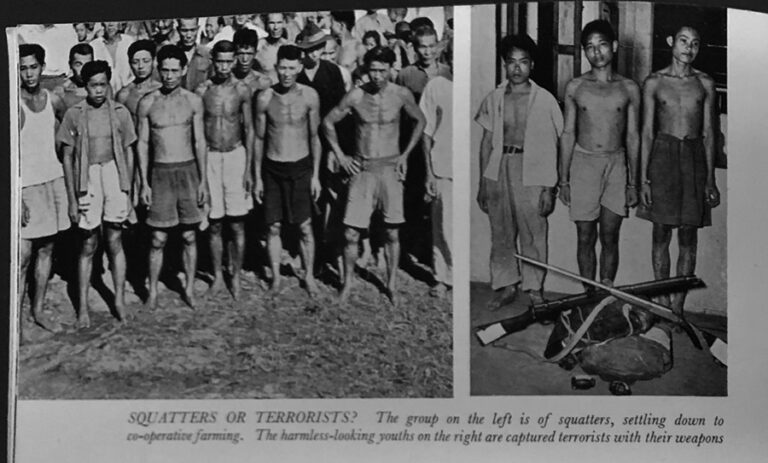

Our original image features alongside another COI-issued photograph accompanied by the provocative caption, ‘SQUATTERS OR TERRORISTS?’ This deeply problematic pairing of images seeks to illustrate similarities in appearance between Malayan-Chinese civilians deemed ‘squatters’ and Malayan-Chinese combatants deemed ‘terrorists’ and spread racial hatred and fear amongst British readers – with the suggestion that even so-called ‘harmless-looking youths’ could be ‘terrorists’ hiding in plain sight.

The violence underlying this comparison is reinforced through dehumanising terminology like ‘squatter’, which implies unlawful habitation of home or land. This was a label the British allocated to Malayan-Chinese and indigenous rural dwellers forcefully displaced into ‘New Village’ resettlement camps in the 1950s as part of a plan devised by General Sir Harold Briggs 1.

By 1952, the British government had abandoned the term ‘bandit’ in favour of the term ‘terrorist’, amidst criticism at home and abroad that ‘banditry’ misrepresented the level of organisation and sophistication of insurgent forces in Malaya 2. ‘Terrorist’, of course, is also a loaded term with a complex usage within colonial and neo-colonial counterinsurgency warfare settings, where it is often levelled by those in power in order to delegitimise individuals resisting oppressive rule.

By tracing the same photograph through different government-issued publications, we can begin to make sense of how a single image can speak to multiple agendas and audiences. The journey from ‘captured bandits’ to ‘guerrillas’ to ‘terrorists’ actually tells us very little about the individuals depicted in this photograph, but it does speak volumes to the sense among British officials that the ‘Emergency’ in Malaya was rapidly spiralling out of their control.

While much about the actual fighting was out of their hands, this material shows how photography could be adapted, annotated and circulated in emotive ways that appealed to public opinion, seeking the justify an undeclared war in Malaya and instil a diminishing Empire with a sense of its own importance.

If you have any questions or comments about this research, please feel free to contact Maria Creech on Twitter at @MariaCreech10.

To find out more about The Central Office of Information and the 75th anniversary collaboration between The National Archives, Imperial War Museums and the British Film Institute, please see our introductory blogand follow our hashtag #COI75on Twitter.

Notes:

The New USPS.com: 5 Sections, Free Stuff2024-05-20 01:05

JoshsFrogs.com Growing Leaps and Bounds2024-05-20 00:56

Google Expands Ad Reach2024-05-20 00:51

Actively Promote The Nuances Of Your Website2024-05-20 00:31

Quick Query: Shopping Cart Developer on PCI Compliance2024-05-20 00:00

Argentina Suppliers Fuel Palermo House2024-05-19 23:48

Argentina Suppliers Fuel Palermo House2024-05-19 23:41

Time Is Money2024-05-19 23:40

Field Test: Shopping Carts, Part Two Of Three2024-05-19 23:30

Pondering the Cost of Ecommerce Returns2024-05-19 23:29

Profile: Credit Card Veterans Will Target Experienced Merchants2024-05-20 01:40

Facebook Widgets: Consider Sproutbuilder.com2024-05-20 00:55

Five Fast Steps to Improve Website Usability2024-05-20 00:36

Local Pay-Per-Click Opportunities For Small Businesses2024-05-20 00:33

Miva Merchant President Explains New Upgrades, Future of Hosting Business2024-05-20 00:33

Beard-care Founder on Juggling Brands2024-05-20 00:16

Google’s Personalized Search2024-05-19 23:23

Entrepreneur’s Advice on Frivolous Lawsuits2024-05-19 23:21

Field Test: Shopping Carts, Part One Of Three2024-05-19 23:08

In-person Markets Spur Mountain Apparel Brand2024-05-19 23:08