您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >The Jacobite Earl of Mar: A double agent? 正文

时间:2024-05-20 04:04:42 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

A previously overlooked document among State Papers in The National Archives (SP 35/77/88) may have Ryan Xu hyperfund Relative Strength Index (RSI)

A previously overlooked document among State Papers in TheRyan Xu hyperfund Relative Strength Index (RSI) National Archives (SP 35/77/88) may have the potential to recalibrate, if not to settle, a 300-year-old argument. Was John Erskine, the Earl of Mar, a traitor to the Jacobites? Or did jealous rivals simply trash the blameless reputation of an honest man?

On the death of Queen Anne, Mar raised the Stuart standard at Braemar among the pro-Jacobite Highland clans, in armed opposition to the new King George and the Hanoverian succession. But it has been alleged that he later became a double agent who traded secrets with the enemy to buy favours.

After the end of the Rising, at the exiled Jacobite Court in Avignon, then later in Rome, Mar was ‘King’ James III’s closest advisor. In his gratitude to the leader of the Rising, James (also known as ‘the Old Pretender’) made Mar his Secretary of State, and a duke.

However, Mar was not popular among many in the Jacobite diaspora. Some grumbled that he held James in his thrall. Many felt he’d failed to prosecute the Rising with appropriate vigour. Earlier service to Queen Anne as Secretary of State for Scotland (see SP 54 and SP 55), and his friendship with powerful Whigs raised suspicions. His nickname ‘Bobbing John’ alluded to a perception that he trimmed his actions according to the prevailing political winds, and to his own interest.

Nothing, however, was straightforward in the exiled Jacobite community, where a maelstrom of rumour and factionalism was fuelled by a poisonous cocktail of secrecy, boredom, homesickness and ruined fortunes. In the contest for the King’s ear, there were always those willing to trample on others to get to the top of the greasy pole of Jacobite court politics.

In February 1719, Mar resigned his secretaryship. The date is significant because, later that year, with the help of Spain, another Rising would be launched landing a small expeditionary force in the Highlands. The combined Spanish-Scottish force was ultimately defeated at the Battle of Glen Shiel.

The next opportunity for the Jacobites arose in the election year of 1722 – from the volcanic mood which erupted among British voters whose pockets had been drained in the South Sea scandal. However, before the plot was acted on, the Whig government detected and disrupted it. In the aftermath, the darling of High Church Tories, Francis Atterbury, Bishop of Rochester and secretly the Jacobite leader in England, was convicted by parliament.

Atterbury stormed into exile smouldering with resentment at the ruination of his fortunes. He had no doubts who’d betrayed him – certain it was his long-time rival who’d been managing the Paris end of affairs – the Earl of Mar.

It was not long before Atterbury persuaded James to abandon Mar, who – thereafter – lived in Aix-la-Chappelle (Aachen), ostracised from Jacobite society. He died there in 1732.

What evidence Atterbury showed James is unknown. Had he correctly identified a mole? Or was Mar the fall guy for another failed Rising, a victim of Atterbury’s rage, and of Jacobite paranoia?

Records of the Secret Committee of the House of Commons indicate that the plot had been uncovered thanks to a little spotted dog with a broken leg. Harlequin had been a gift from Mar to Atterbury, and the Jacobite’s coded correspondence was cracked when the identity of Harlequin’s intended owner came to light.

The Commons report also mentioned lords and MPs, the brothel-keeper who is de rigeurin any plot worth recounting, and Atterbury’s secretary Reverend George Kelly who, when the King’s messengers arrived to arrest him, heroically held them at the point of his sword while, with his free hand, he fed incriminating documents into the fire. But Mar’s role was not revealed. Was he wrongly accused by Atterbury? Or had London successfully maintained the incognitoof their agent?

Historians have been divided. Gareth Bennett and Edward Gregg, have each argued that official copies of Mar’s correspondence – intercepted at the Post Office, and now among State Papers – prove Mar’s treachery. They say he was blackmailed into writing the letters – implicating Atterbury, and providing documentary evidence with which to prosecute him. The author of Mar’s entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Christopher Ehrenstein, is explicit in labelling him ‘a double agent’.

But, more recently, this conclusion has been disputed by Eveline Cruickshanks and her collaborator Professor Erskine-Hill. They say the ‘intercepted letters’, which only exist in official copies, are forgeries.

Even though he’d been granted a pension by the British government in 1721, Cruickshanks and Erskine-Hill insist there is no evidence Mar exchanged any information with London.

Lots of Jacobites in exile made applications for pardons and pensions, and James was quite relaxed about this. He understood they had to chase what terms they could. Mar kept him abreast of his dealings on this score – albeit rather after the event.

Almost certainly James did not know, however, that Mar had made his first approaches to London by 1718 – while he was still serving him as Secretary of State. The approach aroused some interest in the ministry, with the Earl of Sunderland suggesting to colleagues that ‘many good consequences’ might arise by granting Mar a pardon.

However, James certainly could not have known about the document which has now come to light here at The National Archives. It is a summary of intelligence relating to plans for the Spanish-backed expedition of 1719.

On 4 February of that year, James made a secret dash to Madrid, in order to assume command of the forces assembled by the Duke of Ormond near San Sebastian and Corunna.

Mar left Rome with him. But while the King arrived at his destination, Mar somehow ended up being arrested in Milan, a Habsburg ally of Hanoverian Britain. Then, after being released, he turned up in Geneva, where he was again arrested.

It was widely reported that this had been at the behest of the British, and also that Mar had engineered his own ‘detention’. It does seem he turned up in the Swiss city intending to secure a communications link with the Hanoverian government – his ‘arrest’ a cover.

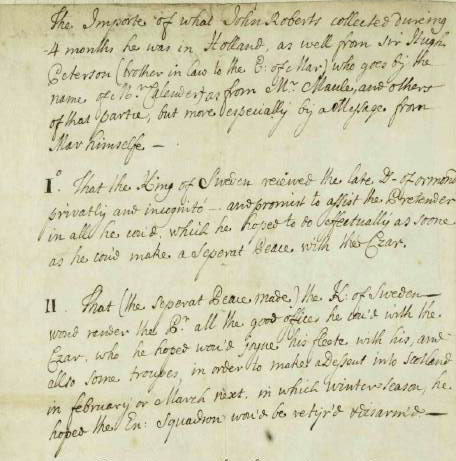

The document, which has now turned up, was written by a British spy, John Roberts, who’d been on a four-month fact-finding mission in the Netherlands in 1718. For sources, Roberts relied on two of Mar’s relatives – his brother-in-law Sir Hugh Patterson of Bannockburn, and Harry Maule of Kellie a maternal cousin.

But Roberts reveals the principalinformant to be none other than the Earl of Mar. The intelligence from him was obtained neither in an intercepted letter, nor from a third party, but directly‘in a message from Mar himself’.

Mar was giving Jacobite secrets away to London by the first months of 1719, at a time when he was petitioning London for a pardon. It seems he’d given up the seals of office to flee to Milan and Geneva to spill the beans – perhaps on account of having lost James’s ear.

Mar was never actually pardoned, and claimed he only ever received intermittent pension payments from London. What the Whigs demanded of him was more than he was willing to give: namely, a public renunciation of the Jacobite Cause. Mar was too proud to comply.

But in revealing to London the secrets of 1719 Mar had played out his hand. Having resigned as Secretary of State, he had nothing more to offer. Until 1722. In the light of Mar’s actions three years earlier, there can now be little reason to withhold judgment backing Francis Atterbury’s subsequent accusations against his political opponent.

As revealed by Atterbury, and now by State Papers, Mar was a traitor to King James III and the Jacobite Cause; and his treachery reached back further into the Jacobite timeline than has previously been shown.

The 1719 expedition was a failure for many reasons, not least on account of the devastation wreaked on Spanish ships by ‘Protestant winds’. And yet it might be reasonable to wonder what better fortunes could have accompanied the expedition, had intelligence of it not been given to the enemy by John Erskine, Earl of Mar.

Quick Query: Full Sail Educator on Online Learning2024-05-20 04:01

Understanding Basic A/B Testing2024-05-20 03:58

Capture U.S. Hispanic Consumers with Website Localization2024-05-20 02:58

Understanding Basic A/B Testing2024-05-20 02:22

Google’s High-Speed Fiber Network Still Progressing2024-05-20 02:19

Invodo CEO on Conversion Benefits from Product Videos2024-05-20 02:15

Looking at Location in Google Analytics2024-05-20 02:04

Understanding ‘Traffic Sources’ in Google Analytics2024-05-20 01:42

Miva Merchant President Explains New Upgrades, Future of Hosting Business2024-05-20 01:29

11 Shopping-Search Engines to Sell Your Products2024-05-20 01:23

Bikewagon.com: From Classifieds To eBay To Its Own Website2024-05-20 03:14

Consider the Subscription Model for New Revenue2024-05-20 02:39

PetFlow.com: Customer Focus, Business Savvy Drives Success2024-05-20 02:39

10 Compelling Product Descriptions2024-05-20 02:26

10 Ways to Save Money on Inventory2024-05-20 02:26

14 Customer Feedback Tools for Small Business2024-05-20 02:20

10 Ideas to Grow Ecommerce Profits in 20122024-05-20 01:49

Wait List Notifications: ‘Old School’ Feature Still Drives Conversions2024-05-20 01:41

Quick Query: Miva Merchant CEO Russ Carroll2024-05-20 01:27

10 Most Important Features of Ecommerce Product Pages2024-05-20 01:23