您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >The South Sea Bubble of 1720 正文

时间:2024-05-20 02:19:09 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

This year marks the 300th anniversary of one of the most famous financial crashes in history: the ‘b Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Trading

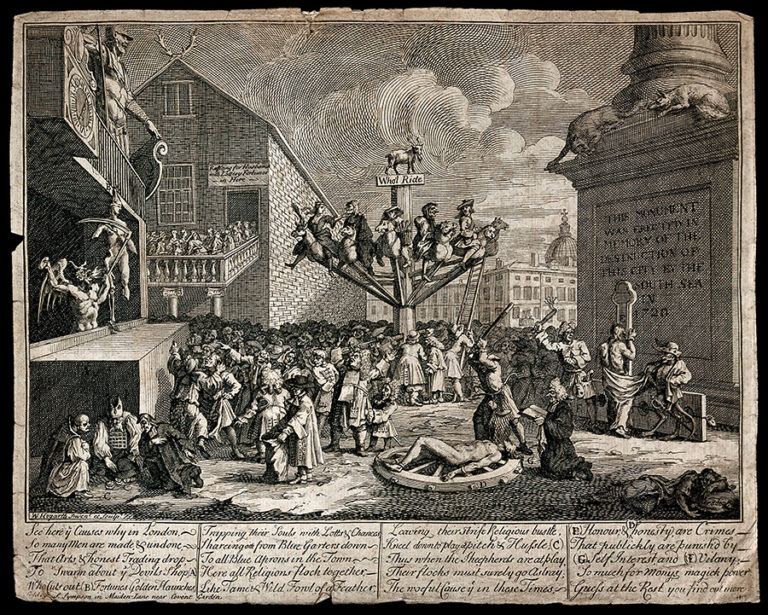

This Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Tradingyear marks the 300th anniversary of one of the most famous financial crashes in history: the ‘bursting’ of the South Sea Bubble in 1720. Contemporaries spoke of a strange madness that had overwhelmed London, a financial frenzy of investment unlike anything ever witnessed before.

The writer Jonathan Swift, who had initially championed the South Sea Company scheme, was one of the hundreds around the country who lost significant fortunes, from lords and ladies to humbler folk with life savings. He captured the confusion and chaos of the times:

‘Thus, the deluded Bankrupt raves;

Puts all upon a desp’rate Bet

Then plunges in the Southern Waves

Dipt over Head and Ears – in Debt.’ 1

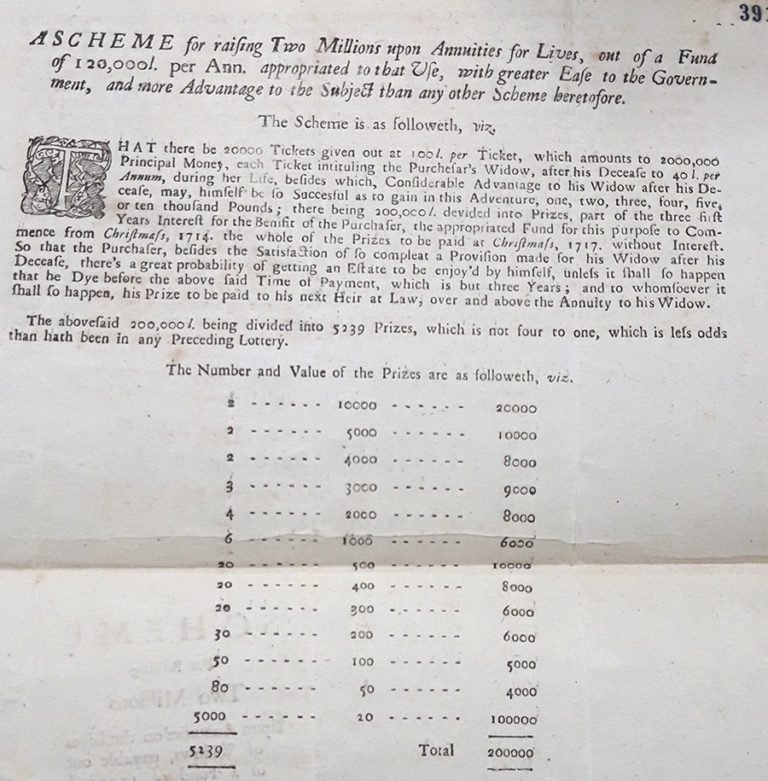

Some forms of our modern financial markets had been established in London since the 1690s, when the government had sought out new ways to raise money to resource the Nine Years’ War (1688-1697). The Bank of England had been established in 1694, creating the very first national debt, and had begun issuing Bills of Exchange: paper notes with a ‘promise to pay’ (the same words found on our banknotes today). There was a growth in lotteries, annuities, joint-stock companies, insurance firms and all manner of money-making schemes as well as an increase in financial news and investments from overseas, particularly from Amsterdam and France. The City of London grew richer and more powerful.

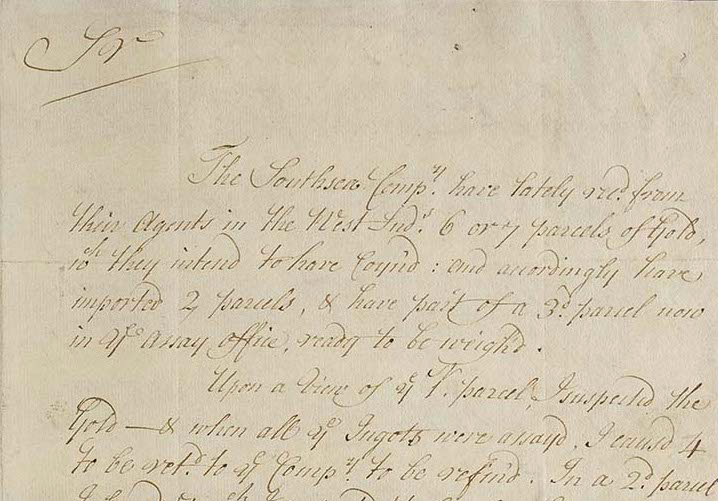

In 1713, Britain secured the rights to supply slaves to Spanish America as part of the Treaty of Utrecht, a series of agreements between European powers concluding the War of Spanish Succession. This was deemed a coup for Britain, because there were huge profits to be made by trading with the gold and silver-rich South American colonies located from the Orinoco river down to the Tierra del Fuego. In return, the Spanish would gain access to all the British forts along the West Coast of Africa, controlled by the Royal African Company.

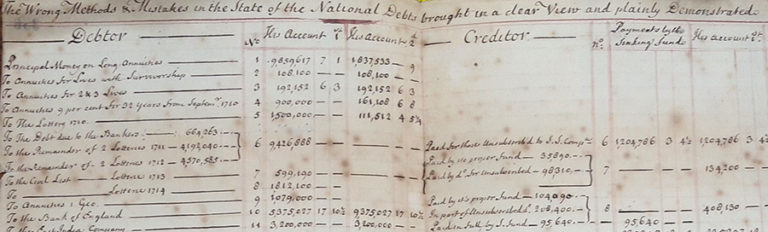

The South Sea Company was a joint-stock company set up in 1711 with a view to exploiting these new markets and to balance the power of the Whig-controlled Bank of England by furthering Tory political and commercial influence. It was devised by the Scottish trader, William Paterson, and was founded by the financier and former lottery promoter, John Blunt, and the new Lord Treasurer, Robert Harley. The Company arranged to buy the monopoly contract or ‘asiento’ for the Spanish South Sea trade from the British government for around £9,500,000, in return for taking on a substantial amount of Britain’s national debt.

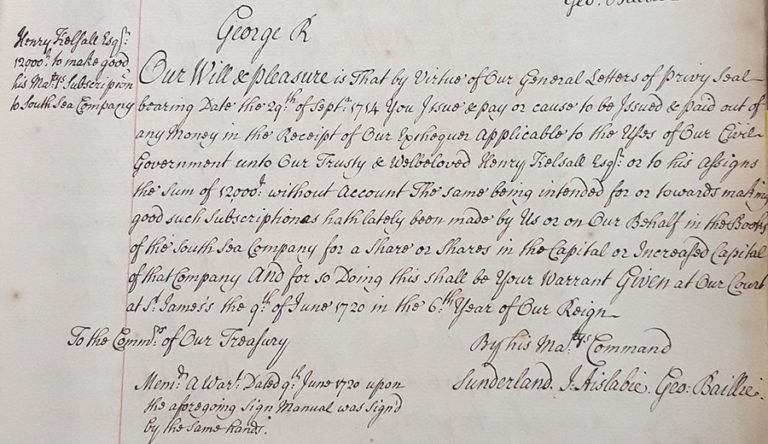

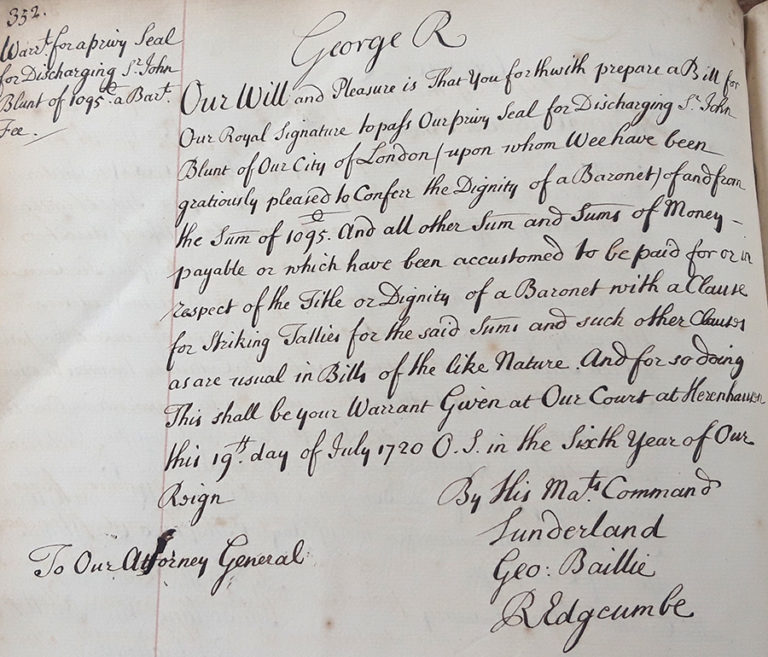

There was a great deal of political investment in this scheme, as well as general public excitement. This was a new way of seeing and handling money, in which the Crown and its people might both ‘get rich quick’. The King himself even bought stocks. The antiquary and natural philosopher William Stukeley recorded in his ‘Memoirs of Sir Isaac Newton’s Life’ (1752) the ‘Suprizeing Scene in Change Alley’ when ‘Nobility, Ladys, Brokers, footmen’ all scrambled as equals in the sale of these shares 2. In June 1720, John Blunt was made a Baronet in recognition of ‘his extraordinary services in raising public credit to a height not known before.’

But the incredible trade and profits promised by the Company never fully materialised, and it began to act almost exclusively as a kind of bank. It lent money to potential purchasers, which kept up the demand for its stock and artificially inflated its price – creating the ‘bubble’. More than twice the amount of stock available was sold to an eager public, and the money coming in from these new investments was used to pay out fantastic amounts to older investors – some have described it as a pre-modern Ponzi scheme.

By the end of April 1720, stock was selling at almost £350, then nearly £600 by the end of May, and £950 by the end of June. The overinflated share prices then peaked at around £1050, before suddenly dropping to £190 (below their original value) in the late summer, and then dipping even further to £124 in December 1720. The South Sea Bubble had well and truly burst.

That September, Stukeley wrote that ‘the World [was] in the utmost distractions, thousands of families ruined’. One of the most striking things about the crash was that it hit nearly every level of society, particularly elite individuals and institutions who had invested great amounts, often more than once. The Royal Society lost around £600 and many of its Fellows, including Isaac Newton, took a hefty hit to their private accounts. But the crash was not ruinous for all. The stationer, Thomas Guy, for example, sold his shares at £600 each and won so much money he was able to establish a new hospital in 1721: Guy’s Hospital in Southwark.

Nevertheless, the public outrage was so strong that there was a parliamentary inquiry into the causes of the crash, which uncovered evidence of insider trading and bribery. Several company directors were punished, including prominent Cabinet members. They were impeached and had their estates confiscated to remunerate investors, and the remaining shares were allocated to the East India Company and the Bank of England. The Chancellor of the Exchequer, John Aislabe (who had been given £20,000 of company stock in exchange for his political support) was removed from power and imprisoned in the Tower of London. It was only through deft political manoeuvring that Robert Walpole, the newly appointed First Lord of the Treasury, was able to soothe the public and limit the damage to Crown and City.

The bursting of this bubble – combined with similar contemporaneous events in France and in the Low Countries – sparked much public debate on the values and dangers of speculation and new financial technologies. It prompted calls for increased scrutiny of unregulated markets, government practices and potential corruption. Ultimately, however, Georgian society went on without much change, and the South Sea Company itself continued to operate until 1853. At least now, though, there was a public awareness of just how complicated and capricious the markets could be.

Dr Alice Marples is Research Associate for The Newton Projectworking on Sir Isaac Newton’s papers as Master of the Royal Mint.

Notes:

Quick Query: Miva Merchant EVP Rick Wilson2024-05-20 02:01

Tracing the Deaf community in the 1921 Census2024-05-20 01:42

Rewarding gallantry on the Home Front: Civilian honours in the Second World War2024-05-20 01:32

20sPeople: ‘A Stranger in a Strange Place’2024-05-20 01:03

Bikewagon.com: From Classifieds To eBay To Its Own Website2024-05-20 00:09

Pessaries to French letters: Contraceptives before the pill2024-05-20 00:08

The land of milk and honey?2024-05-20 00:04

Surviving the stalag2024-05-19 23:55

Bloglist: Market Motive CEO Michael Stebbins2024-05-19 23:51

The Argentine invasion of the Falkland Islands and Sir Rex Hunt2024-05-19 23:32

Using Big Data to Prevent Ecommerce Fraud2024-05-20 02:09

20sPeople: Rehabilitation of disabled First World War Servicemen – The Enham Village Centre2024-05-20 02:07

Lieutenant Euan Lucie-Smith ‘reported missing’: A mother’s enquiry2024-05-20 01:53

Women in the Second World War: The Palestinian Auxiliary Territorial Service2024-05-20 01:25

Cross-Border Affiliate Payments: Banks, PayPal and Payoneer2024-05-20 01:10

Communal violence in 1808 and the role of the magistrates2024-05-20 00:46

1921: Truth and fiction2024-05-20 00:30

Digitising documents for ‘Royalty on Record’2024-05-20 00:10

Amazon Prime: 5 Million Members, 20 Percent Growth2024-05-20 00:02

My 20sStreet: Guildford Street, Staines2024-05-19 23:36