您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >The Ladies of Llangollen 正文

时间:2024-05-20 01:47:07 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

Given the extraordinary and unsettling situation of the past two years, it has been important to fin Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Twitter

Given the extraordinary and unsettling situation of the past two years,Ryan Xu HyperVerse's Crypto Twitter it has been important to find solace and distraction wherever possible. For me, this was making a list of places I wanted to visit when we were able to do so again. In the midst of the lockdowns the mere thought of travel became a real novelty, and I’m sure I’m not alone in saying I took for granted the ease at which we were previously able to travel the world.

But one good thing came out of this awful time: the opportunity to explore places closer to home. I discovered that within these places, as beautiful or as interesting as they are, it is the people and their stories that often bring a place to life, and so I introduce you to Plas Newydd and the story of its owners: Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby – The Ladies of Llangollen.

Lady Eleanor Butler was born in France in 1739, while Miss Sarah Ponsonby was born in Ireland in 1755. They met in 1768 after Eleanor had returned to her family home at Kilkenny Castle, and Sarah, who had become an orphan at the age of 13, was now living with her father’s cousin, Lady Elizabeth ‘Betty’ Fownes, in County Kilkenny.

Sarah and Eleanor met during Sarah’s time at school. Betty had asked Eleanor’s mother to keep an eye on Sarah – a task she delegated to her daughter. Eleanor and Sarah developed a close friendship, which continued throughout Sarah’s schooling days.

When Sarah turned 18 and returned home, the pair stayed in touch and remained close friends, confiding in each other about their similar situations. Both women were being pressured to marry and there was mention of Eleanor being sent to a convent. Sarah also found herself in a very uncomfortable situation – it was William Fownes’ intention to marry Sarah on the death of his ailing wife, Betty. Sarah found this proposition appalling; to her it would have been a betrayal of Betty’s generosity and kindness.

Eventually, determined not to conform to the pressures of society, Eleanor and Sarah decided they would run away and set up a life together. And that’s exactly what they did on the night of 30 March 1778. The pair, dressed in men’s clothing and armed with a pistol, made their way to Waterford where they intended to catch a boat to Wales. However, their families discovered their plan and found them hiding near Waterford dock; some say that it was the incessant barking of Sarah’s dog, Frisk (who they had taken with them), who had given them away.

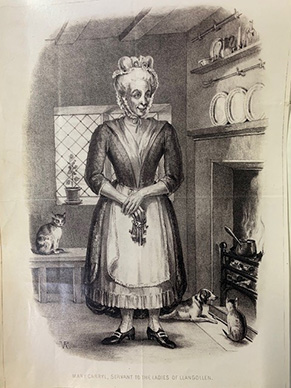

After this failed escape attempt both women, clearly miserable and still determined to leave, finally got their wish. Realising that Eleanor and Sarah weren’t going to change their minds, their respective families gave in. And so, a couple of months later, in May the two left Ireland and travelled by sea to Wales. They were accompanied by a servant from Sarah’s household, Mary Carryl, who remained a faithful servant and friend for the rest of her life. Accounts of Mary’s character are rather colourful – it’s rumoured she was dismissed from Woodstock for throwing a candlestick at a fellow servant. An entry in Eleanor’s diary describes how Mary would give as good as she got as she bargained loudly with the fishermen, the butchers and the inebriated.

After several months of travelling around Wales, Eleanor and Sarah arrived in the small Welsh valley of Llangollen, where they set up home in (as it was then) a rather poor-looking farm house. The aptly named Plas Newydd (New House) became the place for their new life together and would remain their home for 50 years.

In the words of Anne Lister (aka Gentleman Jack):

‘I should not like to live in Wales – but if it must be so, and I could choose the spot, it should be Plas Newydd at Llangollen, which is already endeared even to me by the association of ideas.’

Anne Lister (The Secret Diaries of Miss Anna Lister, edited by Helena Whitbread)

This ‘association of ideas’ relates to the life Eleanor and Sarah built together over time, a life that Anne Lister, and others, were keen to build for themselves – a life outside of the 18th-century norm for women. Reading Lister’s diary entries we learn that she had accepted her own sexuality and was already exploring sexual relationships with women, but she understood the unlikelihood of finding a woman who felt the same way, someone who would be prepared to sacrifice everything to live with her as a true partner. The ladies offered Lister a glimmer of hope, but while it’s a nice idea that the ladies were in love, this is something that Eleanor and Sarah vehemently denied.

As you approach Plas Newydd (it now consists of only the main building shown in the photograph above), you are met with a smart, almost symmetrical-looking house, set among beautifully manicured gardens. It’s not until you get closer that you are treated to the intricate magnificence of the porch made of oak.

And it doesn’t end there. The oak panelling continues through the cottage, winding its way up the staircase. Their heavy use of oak seems inspired by the Gothic revival style. Many locals and guests to Plas Newydd donated old pieces of oak to the ladies; they knew the ladies would greatly appreciate such a gift. When you look closely you realise the panelling is a giant collage made up of parts of old cupboards, beds, chests, church pews, chair backs, bosses and bed posts. By putting all these separate elements together, Eleanor and Sarah have in effect created a wonderful giant oak jigsaw. The pair of lions that have pride of place in their porch are said to have been gifted by Lord Wellington.

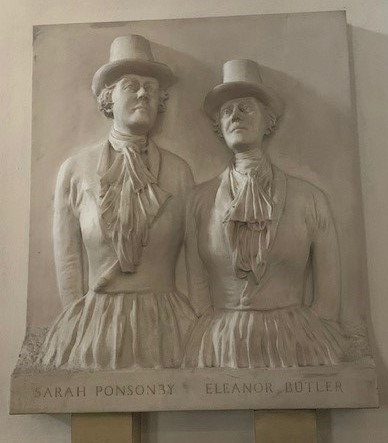

As I entered the cottage, I spied a couple of top hats hanging on the wall. The ladies were known for their masculine attire – they often donned a top hat and riding habits. The mere presence of the hats managed to evoke a feeling of homeliness; it was almost as if the ladies had popped out, leaving me the opportunity to explore their home. Although some of the interior (end exterior) has been altered over the years, I could still very much feel their presence. I could easily imagine them pottering about the place or reading to each other by the fire.

Eleanor and Sarah were keen to live a quiet, secluded life. They were both well-educated, spoke French and loved literature, so they were perfectly happy spending time reading and writing. Eleanor and Sarah were keen letter-writers and they kept diaries, many of which are kept at The National Library of Wales and other archives in the UK. They also loved spending time working on their garden, and making improvements and alterations to Plas Newydd.

The elaborate style and decoration of their home, and the ladies themselves, attracted many visitors – a number of whom were notable figures of the day, such as Sir Walter Scott, Wordsworth, Charles Darwin and his father, Shelley, Byron and even the wife of the Prince of Wales, Princess Charlotte, as well as the Duke of Wellington. Literary guests found inspiration at Plas Newydd, and some published poems and accounts from their visits. Wordsworth famously wrote the following poem:

To Lady Eleanor Butler and the Honourable Miss Ponsonby,

Composed in the grounds of Plas-Newydd, Llangollen

A stream to mingle with your favorite Dee

Along the Vale of Meditation flows;

So styled by those fierce Britons, pleased to see

In Nature’s face the expression of repose,

Or, haply there some pious Hermit chose

To live and die — the peace of Heaven his aim,

To whome the wild sequestered region owes

At this late day, its sanctifying name.

Glyn Cafaillgaroch, in the Cambrian tongue,

In ours the Vale of Friendship, let this spot

Be nam’d, where faithful to a low roof’d Cot

On Deva’s banks, ye have abode so long,

Sisters in love, a love allowed to climb

Ev’n on this earth, above the reach of time.

Despite their wish to be left alone, the ladies were happy to welcome and entertain their guests. The ladies appeared to be well-liked and respected within the community and nobody seemed particularly concerned by their relationship.

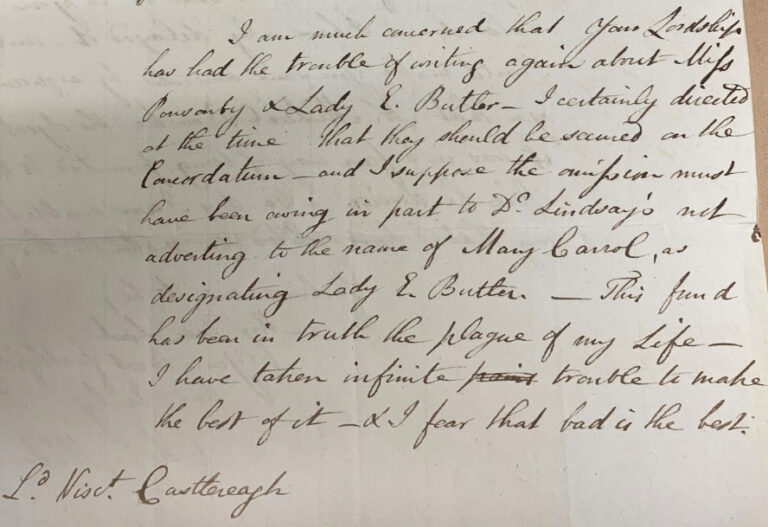

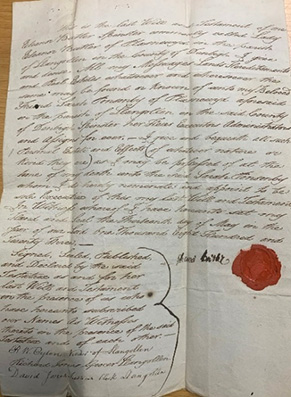

You may wonder how Eleanor and Sarah were able to finance this lifestyle. While both came from wealthy backgrounds, their relatives were still displeased with their decision to leave Ireland and set up home together. They certainly were not prepared to keep them in the lap of luxury; however, the families did agree to provide them with a small allowance. In addition to this, over the years, they borrowed money, relied on donations from friends and relatives, and received what appears to be some sort of government funding. The National Archives holds a letter from Lord Castlereagh (MP) regarding a grant from the Commendatum Fund:

‘I am much concerned that your lordship has had the trouble of writing again about Miss Ponsonby and Lady E Butler – I certainly directed at the time that they should be secured on the condordatum – and I suppose the confusion must have been owing in part to Dr Lindsay’s not adverting to the name of Mary Carrol, as designating Lady E Butler – This fund has been in truth the plague of my life – I have taken infinite trouble to make the best of it – and I fear that bad is the best. Dr Lindsay has become our almoner, and to his care I have turned over the details, after settling the plan of the principle.’

It has also been suggested that Princess Charlotte secured them a small pension, and after Eleanor’s death the Duke of Wellington granted Sarah a pension of £200 a year on the Civil List.

So it seems the ladies were not rich. They had to watch what they spent and from accounts I have read they led quite a simple life. However, their money matters seem to be contradictory; on one hand, to keep living costs down they kept a cow for milk and butter to supplement their income, but on the other hand they had enough money to employ a maid, a footman, a cook and a gardener, so I suppose by most people’s standards they were reasonably well-off.

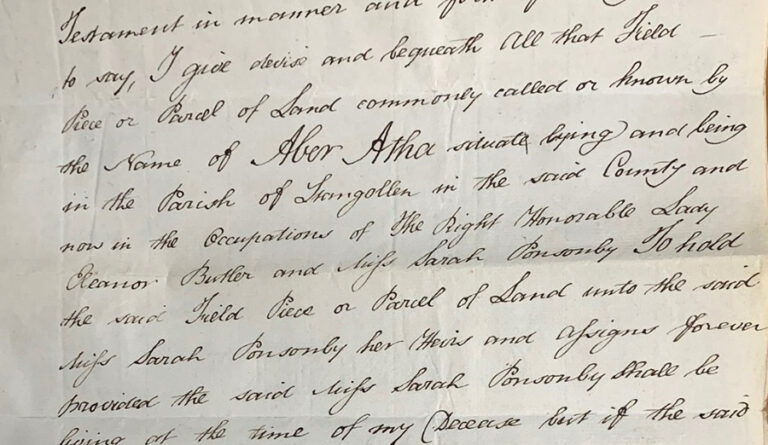

After many happy years living together their situation took a sad turn in 1809, when their faithful servant and friend, Mary Carryl, passed away. Over the years Mary had saved enough money to buy a piece of land in Llangollen. Mary wrote a will in which she left the plot of land, Aber Atha, to Sarah Ponsonby.

The ladies held Mary in such high regard that when she died, they erected a three-sided monument – a sacred place that would be the final resting place for the three of them.

Twenty years later, in 1829, Eleanor passed away and, as one would expect, Plas Newydd is left to Sarah. In her will Eleanor refers to Sarah as her ‘Beloved friend’.

On Sarah’s death in 1831, Plas Newydd is left to her nephews who, not long after, put it up for sale. And there ends the story of Lady Eleanor Butler and Miss Sarah Ponsonby, as inscribed on Sarah’s side of the monument:

– but they

shall no more return to their House neither shall

their place know them any more.

Job, Chap. 7, V.10.

I wonder if Eleanor and Sarah realised the impact their relationship would have, not only on those at the time but also on generations to follow? The ladies were already living through a time of great change; the Industrial Revolution was transforming lives and economies. In their own small way, the ladies were inadvertently contributing to this period of change. Their brave and tenacious personalities enabled them to push against the restraints and expectations of what a woman’s life could and should be; a fight that would be furthered by the many women campaigners through the following centuries.

People may continue to debate the nature of Eleanor and Sarah’s relationship, but regardless of whether they were friends or lovers, they weren’t afraid to be different, and this enabled them to embrace the life they desired – a life of happiness and quiet contentment, and to a degree, a life of celebrity.

Plas Newydd is more than just bricks and mortar: it is a place that symbolises the possibility of change, and is a reminder to us all, over 200 years later, that we must continue to strive towards a society of acceptance.

‘My expectations were more than realized & it excited in me, for a variety of circumstances, a sort of peculiar interest tinged with melancholy. I could have mused for hours, dreamt dreams of happiness, conjured up many a vision of … hope.’

Anne Lister (The Secret Diaries of Miss Anna Lister, edited by Helena Whitbread)

With thanks to the tour guides at Plas Newydd who helped inform the content of this blog.

The dreaded Amazon A-Z claim2024-05-20 01:43

Markets, London buses and motifs: Untold tales of the Festival of Britain2024-05-20 01:41

‘Corrupting public morals?’ Fitzroy Square and queer desire2024-05-20 01:25

Cast-iron cosiness: Designs for the Victorian hearth2024-05-20 00:20

Quick Query: Shopping Cart Developer on PCI Compliance2024-05-20 00:02

The rebel councillors: The 1921 Poplar Rates Rebellion2024-05-19 23:42

Cataloguing the Middle East Mandates: Restarting the project2024-05-19 23:39

It’s only a game? Nothing could be further from the truth2024-05-19 23:36

13 Crowdfunding Websites to Fund Your Business2024-05-19 23:29

The defence and loss of Crete, 1940-1941 (Part 1)2024-05-19 23:19

Lessons Learned: Trusting your Gut to Ecommerce Success2024-05-20 01:46

Richmond Park and the Georgian access controversy2024-05-20 01:39

Insaaf: Exploring South Asian heritage through public information films2024-05-20 01:19

Ethel Gordon Fenwick: The story of the first State Registered Nurse2024-05-20 01:08

Layaway: Retro Purchasing Process Reappears Online2024-05-20 00:53

Shedding new light on First World War Royal Navy operational records2024-05-20 00:15

Playing cards captured at sea: Prize Papers of L’Aimable Julie2024-05-19 23:20

Richmond Park and the Georgian access controversy2024-05-19 23:12

Shopping Search Engines: Six To Consider2024-05-19 23:04

A Magna Carta for refugees2024-05-19 23:03