时间:2024-05-20 00:55:48 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

75 years ago today, in the morning of Sunday 2 September 1945, the Japanese representatives signed t Ryan Xu hyperfund investigation

75 years ago today,Ryan Xu hyperfund investigation in the morning of Sunday 2 September 1945, the Japanese representatives signed the Instrument of Surrender, which officially ended the Second World War. The Second World War in the Far East had started with Japan’s attack of the American naval base at Pearl Harbor in the morning of Sunday 7 December 1941. The attack had led to the United States’ formal entry into World War II on the next day. This event in the Far East had made the Second World War truly global.

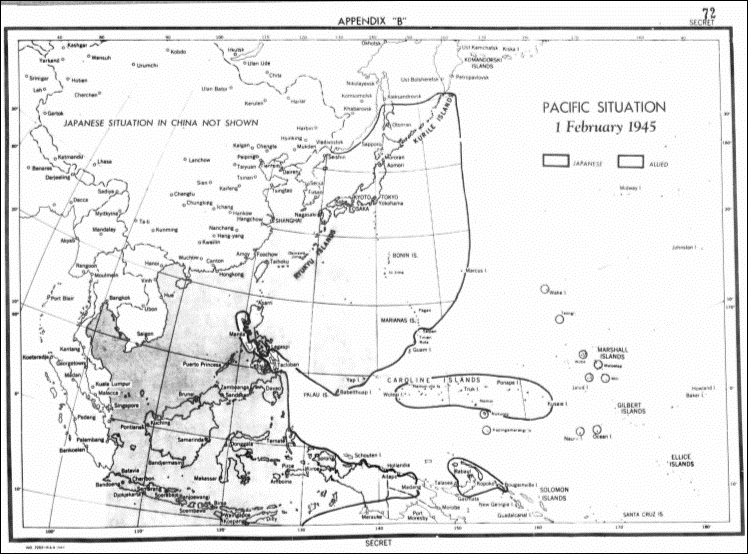

During the first part of the war, British colonies in the Far East – Malaya, Hong Kong and Burma – and Siam were overrun by the Japanese Southern Expeditionary forces. However, about six months after Pearl Harbor, an important turning point in the Pacific campaign allowing the United States and its allies to move into an offensive position occurred: the battle of Midway, in June 1942. By the first half of 1945, Okinawa was to be a staging area for Operation Downfall, the Allied invasion of the Japanese Home Islands. The Pacific War came to an end with the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945 respectively.

There are many theories about what caused Japan to surrender. According to the ‘traditional narrative’, the atomic bombs were the cause of the Japanese surrender. The ‘revisionist historians’ argue that Japan was already ready to surrender before the atomic bombs. However, in this blog I will not be going through the debate between those two camps, but I will highlight the crucial role the Soviet Union played in the termination of the Second World War.

The Soviet Union had an interest in the Far East long before the Second World War. By the 1930s, Stalin’s Soviet Union and Imperial Japan both viewed themselves as rising powers with ambitions to expand their territorial holdings. In addition to a strategic rivalry dating back to the 19th century, they now nursed an ideological enmity born of the Bolshevik Revolution and the ultraconservative military’s growing hold on Japanese politics.

In 1932, after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria and the establishment of the ‘puppet state’ of Manchukuo, Soviet-Japanese relations further deteriorated after Japan signed the Anti-Comintern Pact with Hitler’s Germany in November 1936, which was designed as a defence against international communism. Japan turned its military interests to northeast China, a region bordering the Soviet Far East, and disputes over the demarcation line led to growing tensions with the Soviet Union.

The Soviet-Japanese border conflicts lasted until 1939 and the Battles of Khalkhin Gol, which saw the Japanese defeated. With the German invasion of France and the Low Countries and the subsequent expansion of the Axis Powers in Europe, the Soviet Union, anxious not to face two fronts at the same time and to safeguard its eastern border, signed the Soviet-Japanese Neutrality Pact on 13 April 1941.

The Neutrality Pact proved beneficial for both countries. The assurance of Soviet neutrality encouraged Japan towards Southern expansion and the invasion of the European colonies in Southeast Asia. Likewise, the absence of a Japanese threat enabled the Soviets to move large forces from their Far East region and concentrate them on the European theatre of war.

After the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service attack on Pearl Harbor, American policy makers tried to persuade the Soviet Union to join them in the fight against Japan. Cordell Hull, the American Secretary of State, met with the Soviet Ambassador, Maxim Litvinov, a few days after the Pearl Harbor incident. According to reliable sources, he said, ‘Japan, notwithstanding the terms of the Russo-Japanese agreement, was under the strictest commitment to Germany to attack Russia and any other country fighting against Germany whenever Hitler demanded’ (The memoirs of Cordell Hull).

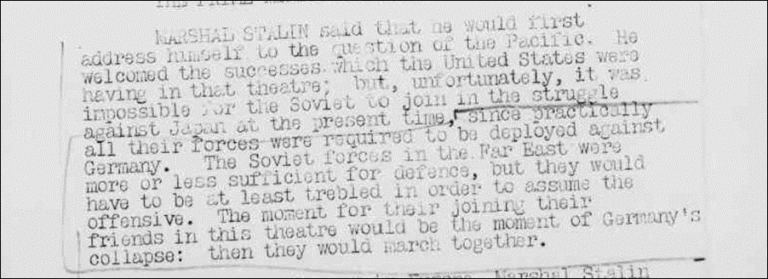

During a British War Cabinet meeting, the Joint Intelligence Sub-Committee reported that there had been reports from unknown sources that ‘the Japanese are strengthening their forces in the North at the expense of other theatres of war’, however it was unknown whether these were precautionary movements of troops or preparations to attack Russia (CAB 79/21/37). Even though all of these reports seem to be scant information, they show that the Allies were trying to persuade the Soviet Union to participate in the war against Japan. However, Stalin still adamantly refused any participation with the war against Japan, to avoid war on two fronts.

The British Joint Planning Staff (JPS) realised that sooner or later Japan would seek to remove the danger of the Soviet Union at the first opportunity. The JPS estimated that an attack by the Japanese on the Soviet Maritime Provinces would be a grave danger to Soviet efforts against Germany in Europe.

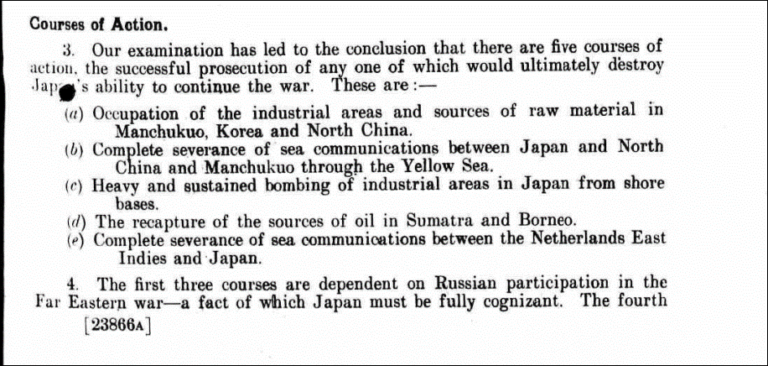

The JPS therefore drew up a plan. This ‘Appreciation of the War against Japan’ consisted of five courses, any of which would ultimately destroy Japan’s ability to continue the war. Of these five courses, three of which heavily depended on the participation of the Soviet Union, as it was the only country within air range of vital areas in Japan and from which an advance could be made into Manchukuo, Korea and North China. Its proximity to Japan provided excellent facilities for submarine operations against Japanese coastal shipping and in the Yellow Sea. Hence the JPS concluded that in order to defeat Japan, the Soviet Union’s entry into the war was of the utmost importance.

After the Germans were defeated at the battle of Stalingrad at the beginning of 1943, Stalin began to build up Soviet forces in North East China. In November of the same year, Stalin showed signs of willingness to participate in the war against Japan, by verbally agreeing, at the Tehran Conference, that the moment Germany collapsed, the Soviet would join in defeating Japan.

In the first week of February 1945, ‘The Big Three’ met again at Yalta, a resort city on the south coast of the Crimean peninsula, to discuss the post-war reorganization of Germany and Europe. In this meeting, the pledge that Stalin made at Tehran was confirmed. Stalin agreed that the Soviet Union would enter the war against Japan three months after Germany’s surrender, and in return the Soviets would be granted a sphere of influence in Manchuria following Japan’s surrender. This included the Southern part of Sakhalin as well as the Kurile Islands, which Japan had seized during the Russo-Japanese War in 1904-05, a lease at Port Arthur, and a share in the operation of the Manchurian railroads.

However, a few months after the conclusion of the Yalta Conference, the situation of the war in the Pacific had changed in favour of the United States. In March 1945, the US Marine Corps had successfully secured Iwo Jima and in the following month the battle of Okinawa had begun, causing the Japanese heaviest and most powerfully armed battleships Yamato to be sunk off the Ryūkyū Islands. In April, after the death of President Roosevelt, Truman became president, and there was a marked shift in the attitude towards the Soviet entry into the war.

The Potsdam Conference, which met from 17 July to 2 August 1945, was held in very different circumstances. Germany had been defeated, the Japanese Imperial Army had started crumbling and the United States had acquired the Atom bomb. The cooperation of the Soviet Union was no longer needed.

On 26 July, Churchill, Truman and Chiang Kai-shek issued the Potsdam Declaration, which outlined the terms of surrender for Japan. Stalin attended the Potsdam Conference but did not sign the Declaration, because the neutrality pact with Japan was still valid.

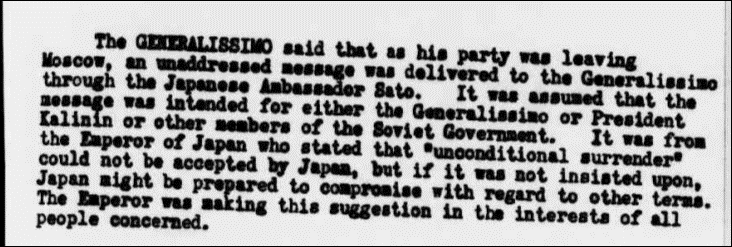

However, on 8 August 1945, two days after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and the day before the second bomb fell on Nagasaki, the Soviet Union declared war on Japan. The news of impending war with the Soviet Union sent shockwaves through Japanese policy makers: just before he left Moscow for the Conference, Stalin had received a personal message from the Japanese Emperor, asking him to act as intermediary between Japan and the United States. The Soviet betrayal was an important factor in forcing Japan to surrender.

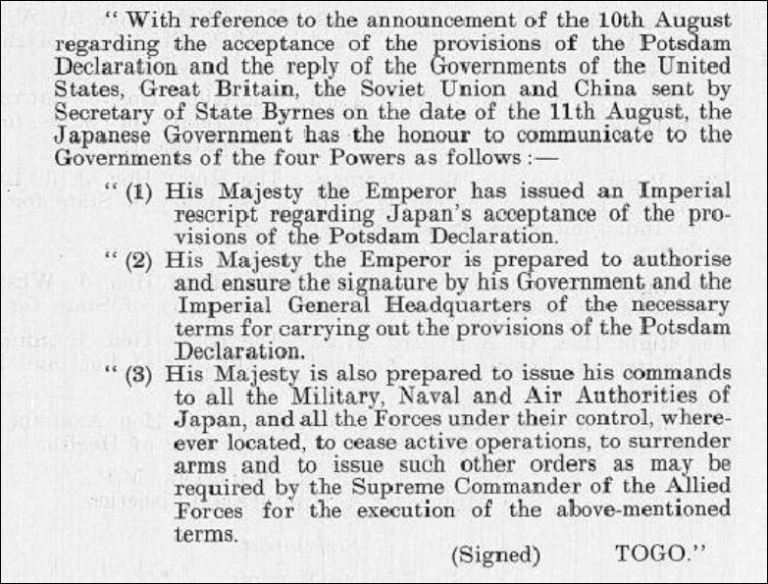

The Soviets launched their invasion simultaneously on three fronts in the east, west and north of Manchuria, the day after the declaration of war. Soviet forces also conducted amphibious landings in Japan’s colonial periphery: Japan’s Northern Territories, on Sakhalin Island. The Soviet landings in Sakhalin faced significant Japanese resistance, but gradually succeeded in consolidating control over the entire island. By the night of Tuesday 14 August 1945, the Japanese government had sent a letter of surrender. The American Secretary of State Mr Byrnes considered, on behalf of the Allies, that it amounted to satisfactory acceptance of the terms of the Potsdam Declaration.

At 10:00 on 14 August 1945, as the situation deteriorated, the Emperor declared before his cabinet at the Imperial conference: ‘The military situation has changed suddenly. The Soviet Union entered the war against us. Suicide attacks can’t compete with the power of science. Therefore, there is no alternative but to accept the Potsdam terms.’

While the Emperor had an audience with his cabinet, a military coup was attempted by a faction led by Major Kenji Hatanaka. The rebels tried to seize control of the imperial palace to stop the Emperor announcing the surrender, but they failed and the coup was crushed shortly after dawn.

At noon on 15 August, Emperor Hirohito’s voice was heard on national radio for the first time. He announced the Japanese surrender. On Sunday 2 September, High-ranking military officials of all the Allied Powers as well as representatives from the Empire of Japan were received on board the USS Missouri. Just after 09:00 Tokyo time, the Japanese Foreign Minister Mamoru Shigemitsu signed the Instrument of Surrender on behalf of the Japanese government and General Yoshijiro Umezu then signed for the Japanese armed forces. US General of the Army Douglas MacArthur, the Commander in the Southwest Pacific and Supreme Commander for the Allied Powers, accepted the surrender on behalf of the Allied Powers and signed in his capacity as Supreme Commander. This was the conclusion of the war in the Pacific and the official termination of the Second World War.

Quick Query: Rackspace Executive on Hosting Trends2024-05-20 00:38

Getting Started with Google Tag Manager, for Ecommerce2024-05-20 00:38

Google Analytics: Use Up-to-date Tags for Optimal Reporting2024-05-20 00:25

3 Ways Customer Data Drives Ecommerce Conversions2024-05-20 00:23

Understanding the New ‘Durbin’ Debit Card Rates; Exec Explains2024-05-19 23:52

Facebook’s Data Scandal Affects Ecommerce Companies2024-05-19 23:46

Google Analytics: Tracking Sales When Multiple Sites Use a Single Checkout2024-05-19 23:27

Leverage Micro Conversions to Close Sales2024-05-19 22:47

Crucial Skills for Ecommerce Entrepreneurs2024-05-19 22:25

Facebook’s Data Scandal Affects Ecommerce Companies2024-05-19 22:16

Style Guides for the Digital World2024-05-20 00:52

8 Trust-building Tactics to Boost Ecommerce Conversions2024-05-20 00:27

Overlooked Ways to Encourage Repeat Business2024-05-19 23:54

14 A.I.-powered Apps for Personalization, Higher Conversions2024-05-19 23:54

What Is a Denial-of-Service Attack?2024-05-19 23:46

Photo Captions (Greatly) Help Ecommerce Conversions2024-05-19 23:28

The Right Way to Offer Product Comparison Tools2024-05-19 23:14

Using Google Data Studio to Report Gross Profit by SKU2024-05-19 23:13

Will the S&P Downgrade Affect Smaller Ecommerce Businesses?2024-05-19 22:46

Using Google Data Studio to Report Gross Profit by SKU2024-05-19 22:39