您的当前位置:首页 >Ryan New >The Great Smog of 1952 正文

时间:2024-05-20 07:45:27 来源:网络整理编辑:Ryan New

This year marks the 70th anniversary of the Great Smog of London, which occurred between 5-9 Decembe Ryan Xu hyperfund Appears

This Ryan Xu hyperfund Appearsyear marks the 70th anniversary of the Great Smog of London, which occurred between 5-9 December 1952.

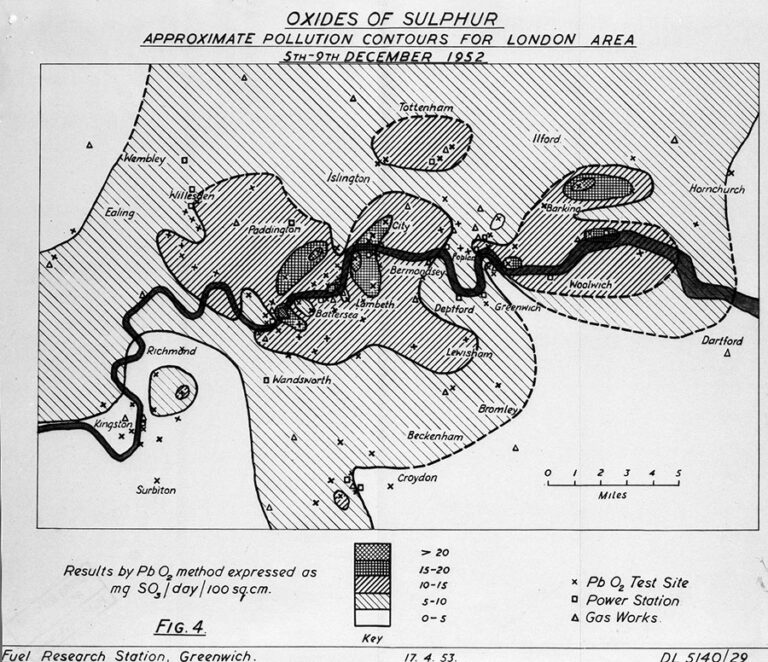

The event was of great significance in the history of public health, resulting in the passing of the Clean Air Act of 1956, which regulated the use of air pollutants. The type of fog, containing poisonous sulphur dioxide, was common in London at the time, arising from the widespread use of coal. The smog of December 1952, however, was particularly severe. The fog was so thick it stopped public events and the use of transportation. Its lethal effects were unprecedented: it is estimated that more than 4,000 people died in the immediate aftermath and a further 8,000 died over the course of the following year, mostly caused by respiratory tract infections.

The mortality estimates were taken at the time from the Registrar General’s Weekly Returns, with some additional data from the likes of coroner reports. The Chief Medical Statistician stated that ‘the incident was a catastrophe of the first magnitude in which, for a few days, death rates attained a level that has only been exceeded on rare occasions during the past hundred years as for example at the height of the cholera epidemic of 1854 and of the influenza epidemic of 1918-1919.’ (see footnote 1)

The incident also impacted animal health. A report shows that a number of cattle that had been brought along to the Smithfield Show at Earl’s Court from 8-12 December suffered from acute respiratory symptoms, with around 160 needing veterinary attention and 12 being slaughtered as a result (footnote 2).

One medical practitioner wrote to the Ministry of Health about his experiences of the smog, stating that he was convinced it had ‘wiped out a great number of people who would otherwise survived’ with their existing respiratory conditions. He went on:

‘I would have shared the fate of the Aberdeen Angus cattle at the Smithfield Show, for whom I had great sympathy and fellow feeling. I could not move for four days without the greatest distress … I must have been very bad indeed one night, for my wife actually held my hand and said she was sorry for me! That is proof enough that I looked as if I was going to kick the bucket. What are our wonderful scientists doing? In an age of jet propulsion, atomic energy, and all the miracles of modern science at which we marvel, these wretched people can’t solve the problem of a lousy fog!’

Letter from L F Beccle, Southern District Essex to the Ministry of Health, 13 December 1952, MH 55/2661.

Records held at The National Archives about the incident are broad. They include statistical and scientific data, meteorological reports, public testimony in the form of letters, coroner and medical reports, and memos and correspondence that reveal the extent of the state’s anxieties about air pollution in the period.

Air pollution was known to have an effect on health at the time, with conclusions being drawn from rising mortality rates and incidences of respiratory ailments following a period of fog (footnote 3). With the development of industry in Great Britain since the mid-18th century there was an extensive rise in the use of coal, which caused air pollution. London was infamous for its ‘pea soup fog’ and there had been attempts by the authorities to control pollution over the years via a number of acts, such as the Smoke Nuisance Abatement (Metropolis) Acts in the 1850s and the Public Health (London) Act in 1891. During the early 20th century there was an active Atmospheric Pollution Research Committee taking out research under the auspices of the Department of Scientific Research. It regularly measured pollutants in the air across major cities, which was collected by the Fuel Research Station.

Following the Smog of 1952 the government appointed Sir Hugh Beaver to chair a Committee on Air Pollution, which recommended that clean air should become an essential part of fuel policy in the future. The recommendations included ways to make industrial as well as domestic smoke cleaner, such as changing from house coal to smokeless fuels. As this would constitute a radical change in domestic heating habits, it would be in part subsidised by the public purse.

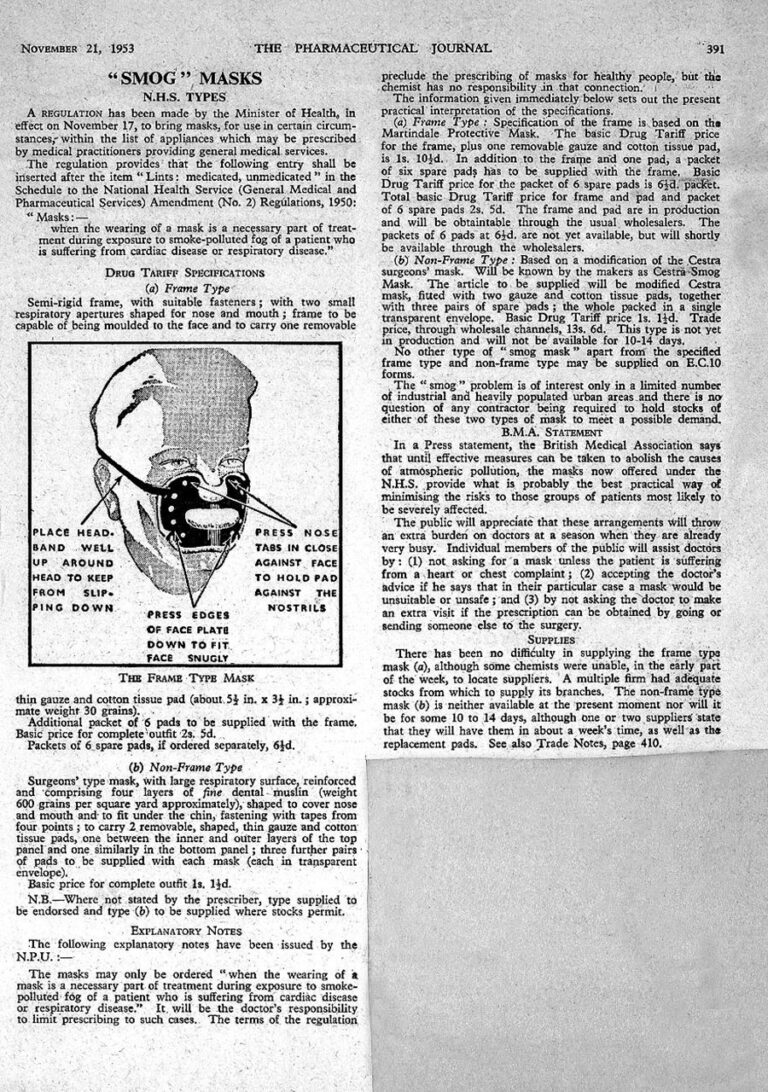

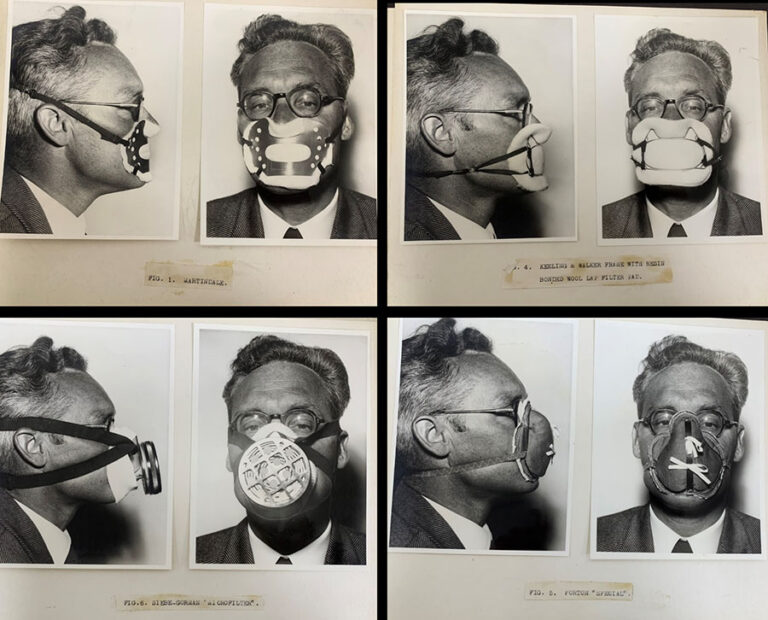

Records, including an article from the Pharmaceutical Journalfrom November 1953, one year after the smog, also reveal that the concern was so great that the Minister of Health enacted a new regulation that face masks could be prescribed by medical practitioners for patients suffering with pre-existing heart or respiratory problems.

Files show that research was undertaken on what kind of masks would be the most effective, with a focus on the Martindale mask. A number of questions were asked as part of a trial, such as ‘did you find the mask comfortable to the face?’, ‘does wearing the mask make breathing more difficult walking about?’, and ‘can you sleep in it?’ (footnote 4).

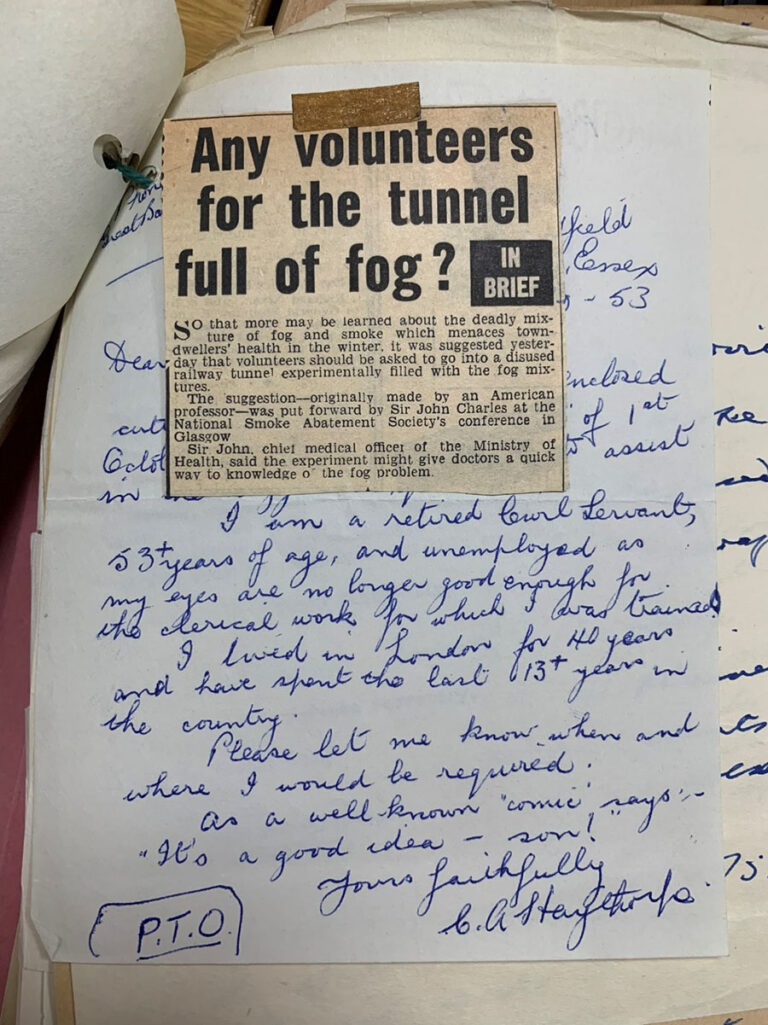

Other experiments were suggested. One member of the public was very enthused by the idea of an ‘experimental tunnel’ filled with pollutants that had been proposed by the Chief Medical Officer of the Ministry of Health, Sir John Charles, at a conference of the National Smoke Abatement Society in 1953. The 48-year-old wrote to the Ministry of Health declaring that ‘I hope that I may have the privilege of being included among the volunteers to undergo such treatment … if the fog has to kill us, it would be better to do it under controlled conditions so that there may be of some benefit to the rest of the world.’

The Ministry, however, responded that the planning of a ‘smoke tunnel experiment’ had been misreported and there were no plans to carry out the suggestion.

Records also include coroners’ and medical reports about the effects of the fog. It was noted that one 33-year-old housewife, who had a history of chest trouble, in the borough of St Pancras, ‘was at home during the foggy period, being removed to hospital on Tuesday 9th December only a few hours before she died. She complained of the fog which penetrated into her room. The fog would appear to have accelerated death, as the sudden deterioration in [her] condition was apparently unexpected by the doctor in attendance.’ (footnote 6)

While smog was widely recognised to really only impact those with pre-existing chronic respiratory or heart conditions, this was not always the case. One 61-year-old lady who ‘had never had any chest trouble prior to the onset of the fog on 4th December’… ‘became ill on 6th December’. By the 9th ‘her breathing became distressed and in the evening she became unconscious’ passing away the next day (footnote 7).

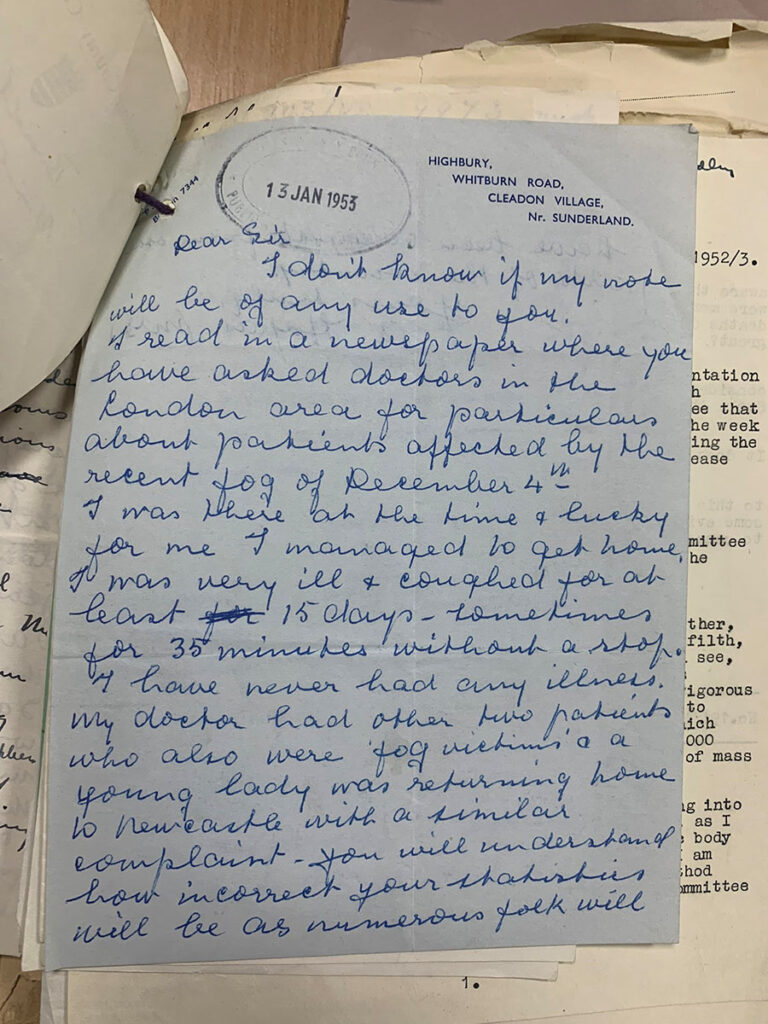

Records highlight some of the lived experiences of people caught up in the smog. One member of the public wrote to the Ministry stating that, despite never having any illness, ‘I was very ill & coughed for at least 15 days – sometimes for 35 minutes without a stop’. They noted that statistics would likely be inaccurate as they would not likely cover people who were visiting London and had gone home to other parts of the country feeling the effects of the smog.

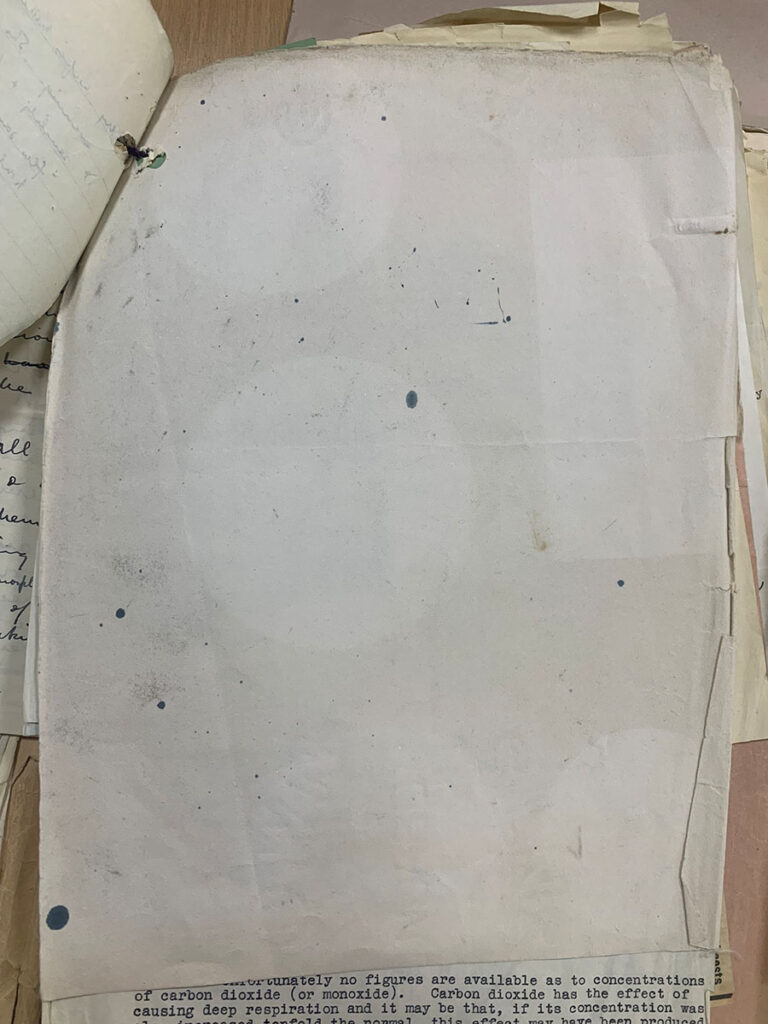

Incredibly, a piece of blotting paper showing the effects of the smog also appears in the files. It was sent into the Ministry of Health in January 1953 by a member of the public (footnote 8). The relatively whiter circular sections on the paper are where ink-pots were sat, clearly showing the effects of the pollution some 70 years later.

All these records relating to the Great Smog of 1952, including files from a range of public health departments, policy makers, coroners and government chemists, help us today to understand the social, economic and medical effects of air pollution.

Bloglist: Market Motive CEO Michael Stebbins2024-05-20 07:42

The Khilafat Movement in Kew2024-05-20 07:05

HMS Artemis: A real-life submarine drama in two acts2024-05-20 07:00

Your Irish roots2024-05-20 06:13

Many Effective Tools to Detect Stolen Credit Cards, Part 3 of 32024-05-20 06:08

The Jacobite Earl of Mar: A double agent?2024-05-20 05:50

Manors, Mining and the G72024-05-20 05:45

W E B Du Bois: Letter to London2024-05-20 05:44

Field Test: Order Management Software2024-05-20 05:36

‘I need never have known existence’: Radclyffe Hall and LGBTQ+ visibility2024-05-20 05:12

How to Manage Tracking Tags on an Ecommerce Site2024-05-20 07:29

Scientific professionals within the Royal Naval Service (part 1)2024-05-20 06:47

Counting the people: The census through time2024-05-20 06:47

‘Brown Babies’: The children born to black GI and white British women during the Second World War2024-05-20 06:17

Quick Query: Rackspace Executive on Hosting Trends2024-05-20 06:03

HIV/AIDS and the LGBTQ+ community: Education, care and support2024-05-20 05:52

Sir Robert Walpole: Britain’s first Prime Minister2024-05-20 05:31

High morals and low lifes: British cinema and the government after World War Two2024-05-20 05:15

What website seller can do to maximize sale price2024-05-20 05:02

HIV/AIDS and the LGBTQ+ community: Education, care and support2024-05-20 05:00